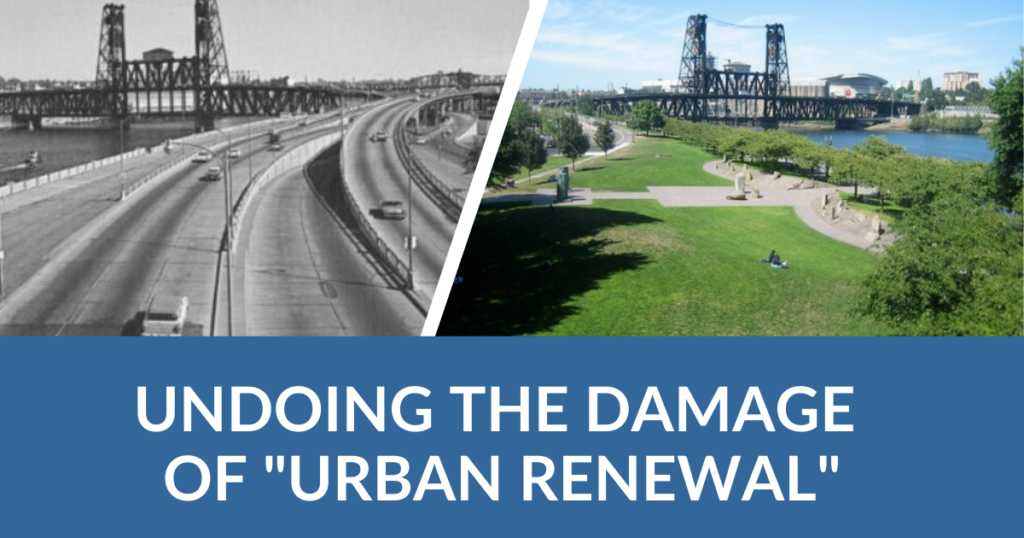

A policy proposal to undo the damage of “urban renewal”

Transportation for America and Third Way released a policy proposal to undo the damage of “urban renewal” projects that have displaced more than a million Americans since construction of the Interstate Highway System and that continue to harm communities of color today. These four federal policy recommendations can be included in a COVID-19 stimulus bill or infrastructure package, or considered as stand-alone legislation.

So-called “urban renewal” initiatives of the 1950s and 1960s ostensibly provided money to cities across the country to revitalize neighborhoods. But in practice, these new interstates razed housing and ripped through neighborhoods, displacing more than a million Americans during the first two decades of the federal interstate system.1 These projects deliberately targeted communities of color and particularly Black neighborhoods, wreaking havoc on their health and local environments for decades.

The American public has made it very clear that they want the federal government to prioritize revitalizing our nation’s infrastructure. Both parties in Congress and the incoming Biden Administration ostensibly agree on this need. Absent a new approach, however, even re-investment risks perpetuating the inequitable highway construction practices of the past while locking in air, water, and climate pollution that are a drag on our health and the economy.

To undo the far-reaching damage of “urban renewal” projects, Third Way and Transportation for America recommend a suite of policies, including the creation of a new competitive grant program, to reconnect communities, repair the damage, and invest for sustainable and equitable growth. This includes:

- Creating a competitive grant program to redesign or deconstruct the outdated infrastructure that has hindered the growth of low-income and minority communities;

- Establishing land trusts to help generate wealth for the communities that already reside in these neighborhoods; and

- Updating federal transportation modeling tools so that decision-makers and communities can see how these infrastructure projects really impact traffic patterns today;

- Requiring federal agencies to issue guidance on identifying communities with infrastructure barriers, measuring the degree of harm to that community, and providing incentives and prioritizing resources to address those disparities.

This critical investment could feature in a COVID-19 stimulus bill or separate infrastructure package, or as stand-alone legislation.

Background

After Congress enacted the 1956 Highway Act, cities and states used primarily federal funding to build highways through the middle of cities. White families used these interstates to move to the suburbs. City planners worried that their city centers would empty out if the suburbs were disconnected from downtown, so they intentionally ran new highways downtown to ensure suburban residents would regularly drive into town. But city developers also often deliberately chose highway routes in order to displace, disrupt, or segregate neighborhoods of color.2

The divisive southeast/southwest freeway in DC. Photo taken in 1968. Photo by DDOT via Flickr.

The displacement has caused profound and generational impacts on these communities and has created huge physical divides in areas that would otherwise be among the most valuable for the city, especially at a time when cities’ downtowns are revitalizing. These highways destroyed the wealth built up through property by the families whose homes cities took through eminent domain or that developers destroyed. Now, residents cannot enjoy the current benefits of a downtown resurgence because of the infrastructure next to them.3

The urban highways cutting through these communities also brought additional, longer car trips; more congestion on the roads; and more pollution. The air quality issues associated with vehicle emissions disproportionately impact communities of color, with these communities facing higher exposure to harmful pollutants4 and greater risk of asthma and other health issues5 than predominantly white communities. These highways, and the sprawl they enabled, have also harmed the climate by increasing Americans’ reliance on motor vehicles: Transportation is now our largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, most of which come from cars and trucks.6

Increasingly, state and local governments are reaching an inflection point. Many of these highways are aged half a century or older and have either fallen into disrepair or are no longer needed because of changing traffic patterns. Rather than simply replace or expand these highways, cities and states should reconsider whether these highways are necessary routes or unnecessary barriers that continue to cut off neighborhoods of color from opportunity.

The idea of legislating to undo the damage of past “urban renewal” policies isn’t new: under President Barack Obama, Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx convened stakeholder meetings on how to make transportation more affordable, accessible, and equitable.7 President-elect Joe Biden’s inauguration—and House and Senate infrastructure leaders’ commitment to improving America’s roads and bridges—could give new currency to this work.

Policy recommendations

Authorize $10 billion for a new Restoring America’s Neighborhoods Grant program to correct the economic, environmental, and social damage of “Urban Renewal” highway projects that destroyed the core of many small, medium, and large US cities and displaced communities of color.

Half of this funding would be awarded to state DOTs to redesign or deconstruct highways or other transportation infrastructure that was built through communities of color (“obstructive highways”). The other half would fund the creation of land trusts in those neighborhoods to ensure the land freed up from the removal of obstructive highways will generate wealth for the people who already live there.

Redesign or deconstruction of obstructive highways

What the sunken, divisive Rochester Inner Loop used to look like, before being filled in and replaced with a surface boulevard. Flickr photo by Friscocali.

The US Department of Transportation (USDOT) should make grants available to state DOTs in partnership with the affected cities. Eligible projects for grants under this program would be for removal or repurposing of obstructive highways, including bringing the highway to grade, reconstructing the local roadway network, turning the highway into a boulevard, etc. There should also be a planning set-aside for assessing, designing, permitting and engineering alternatives for specific obstructive highways as well as setting up a land trust, including forming the trust and providing it authority to operate in the area. This work could include measurements of the air and water pollution impacts of retaining or repairing existing disruptive highways versus removing or replacing this infrastructure.

A $5 billion investment could fund a couple of large projects and 6-10 smaller ones, depending on the size of the obstructive infrastructure. These grants will be sufficient to fully fund a project, to ensure these projects can move forward quickly. USDOT should give preference to applicants with a demonstrated capacity—including any locally matched funding—to develop and manage the project; those that have an existing partnership with the communities impacted; and those whose projects demonstrate equitable economic development, a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, supportive land uses, new transit service, or explicit protection of housing affordability.

To maximize the impact of these investments for economic stimulus, USDOT should reward the first grants no later than nine months after the program is enacted and should strongly prioritize funding to projects that can be completed within 5 years. USDOT should also require projects receiving grant funding to adhere to the labor provisions that usually come attached to federal-aid highway funding, such as Davis-Bacon prevailing wage standards and Buy America domestic content provisions.

Land trusts

The interstates that the Highway Act supported consistently destroyed wealth in the communities they traversed and divided, particularly in communities of color. Therefore, any projects that begin to reverse this damage should rebuild that wealth. Highway update projects that remove a barrier, create new greenspace, or connect the community to commercial centers will also increase land values. To ensure that neighborhoods around the highway receive the benefits of its removal or modification, the project sponsor for any award under this program should be required to establish a land trust or land bank that would receive initial ownership of any property that becomes developable through activities supported by a grant under this program. The land trust would help locals buy the property, preserve and build affordable housing, support the opening of locally-owned small businesses, and preserve greenspace and parks.

A $5 billion investment could support 1-2 dozen land trusts for five years. The sale of property and development of land recovered should both fund the land trust beyond its first five years and help existing homeowners pay the increase in property taxes once their property values appreciate due to gentrification. The program should also protect renters, as well as homeowners who have owned affected buildings for generations but who cannot show title. It must ensure that housing affordability remains protected before, during, and after development. The USDOT should work directly with the Department of Housing and Urban Development to establish the land trust portion of this program, determine awards and manage the grants.

Policy considerations

This paper only introduces the Restoring America’s Neighborhoods Grant program and its key principles; it’s not meant to spell out every detail or present legislative text. However, policymakers and others interested in advancing this program will need to think through some additional policy considerations regarding the land trust component of the program, such as:

- Whether to include a requirement that the land trust act with a fiduciary duty to the local community;

- Whether to require that a grantee already have a land trust, or similar non-profit, already established and operating in the area; and

- Whether to funnel this money through an existing program like the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program in order to get funding awarded quickly.

Forecasting tools

Transportation agencies do not yet have the necessary tools to understand the impacts of various highway project alternatives on traffic, urban development, and climate change. Today’s traffic forecasting tools are not built to consider individual trips that shift to other corridors; occur at a different time of day; involve a different mode of transportation; or disappear due to telecommuting or a shifted trip. Our proposal includes $25 million for USDOT to develop twenty-first century tools capable of accounting for these shifts in traffic in order to help plan and to preserve affordability in travel.

Study on obstructive infrastructure

Too many communities suffer the burden of infrastructure barriers without the political or economic power to oppose harmful projects and secure beneficial investments. Meanwhile, the federal government spends billions in formula and discretionary funds, often perpetuating the cycle of harm to communities. To break this cycle, and better target investments, our proposal will require USDOT to conduct a broader study, with the support of state DOTs and impacted cities, identifying the communities with infrastructure that creates barriers to mobility (such as highways that slice through a community) and measuring the degree of harm to that community. This study will culminate in the creation of a national map of communities torn apart by infrastructure, and will help prioritize resources for the communities most badly harmed by obstructive highways in the future.

Examples of successful reversals

Many cities across the country have already removed urban freeways and other infrastructure that has hindered the growth and vitality of their communities. These successes can serve as a model for a federal program.

In the 1970s, Portland became the first major city to remove an existing highway when it tore out Harbor Drive and replaced it with a public park that has served as an anchor for new development. Milwaukee tore down the Park East Freeway in the early 2000s, attracting over $880 million in private investment to the 24-acre corridor. In Greenville, South Carolina, the city replaced a four-lane highway bridge with a pedestrian bridge and public park, a project that revitalized its West End and spurred over $100 million in private investment in its first two years.

The pedestrian bridge in Greenville’s Falls Park on the Reedy that replaced a highway, spurring over $100 million in private investment in its first two years.

There are also examples of communities establishing land banks to bring economic value to low-income communities and communities of color and help underserved families stay in their homes. Launched in 2003, Denver’s Urban Land Conservancy preserves and develops permanently affordable real estate to ensure underserved communities are not displaced by rising property values. Through the conservancy and other partners, the Denver Transit-Oriented Development Fund is working to secure over 1,000 affordable housing units on transit corridors. In Minneapolis, the Twin Cities Community Land Bank has acquired at least 1,000 vacant or distressed properties since 2009, keeping these properties affordable and helping low-income families stay in their homes.

Positive impacts

The United States has an opportunity to replicate these success stories by providing cities with the proper resources and tools to tackle these projects. Through a $10 billion program, dozens of cities could plan and repurpose their disruptive highways and reclaim significant acreage for tax-paying, job-creating redevelopment.

This grant program would improve regional air quality and health outcomes in disadvantaged communities by reducing exposure to smog. It would reconnect impacted neighborhoods, create new open spaces and allow people to take shorter trips to reach daily necessities like the grocery store or community center. It would increase access to less polluting modes of travel, like walking and biking. It would reduce climate pollution in areas that research already indicates will suffer a greater burden from the impacts of climate change. Most importantly, it would be a step toward rectifying the mistakes of past federal policy and moving us forward in a brighter direction.

Endnotes

- Pyke, Alan, “Top infrastructure official explains how America used highways to destroy black neighborhoods.” Think Progress, 31 Mar. 2016, https://archive.thinkprogress.org/top-infrastructure-official-explains-how-america-used-highways-to-destroy-black-neighborhoods-96c1460d1962/.

- Kruse, Kevin M, “What does a traffic jam in Atlanta have to do with segregation? Quite a lot.” New York Times Magazine, 14 Aug. 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/traffic-atlanta-segregation.html.

- Semuels, Alana, “The role of highways in American poverty.” The Atlantic, 18 Mar. 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/03/role-of-highways-in-american-poverty/474282/.

- De Moura, Maria Cecilia Pinto and David Reichmuth, “Inequitable exposure to air pollution from vehicles in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic.” Union of Concerned Scientists, 21 Jun. 2019, https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/inequitable-exposure-air-pollution-vehicles.

- “Disparities in the impact of air pollution.” American Lung Association, 20 Apr. 2020, https://www.lung.org/clean-air/outdoors/who-is-at-risk/disparities.

- “Fast facts on transportation greenhouse gas emissions.” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, accessed 4 Dec. 2020, https://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/fast-facts-transportation-greenhouse-gas-emissions.

- Beyond Traffic 2045, U.S. Department of Transportation, 9 Jan. 2017, page 206, https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/docs/BeyondTraffic_tagged_508_final.pdf.