Fired up? Please take action and tell your member of Congress to support emergency assistance for transit agencies.

Congress and the president are considering ways to provide much-needed boosts to the economy due to the impacts of the novel coronavirus. But simply pouring money into the existing transportation program as a whole will fail to help the people who rely on transit to access the health care system and will have impacts on transit service that will last for years to come. Here are some ways Congress could provide targeted assistance to transit and the people that rely on it in the weeks and months ahead.

MTA New York City Transit sanitizes stations and subway cars. (Marc A. Hermann / MTA New York City Transit)

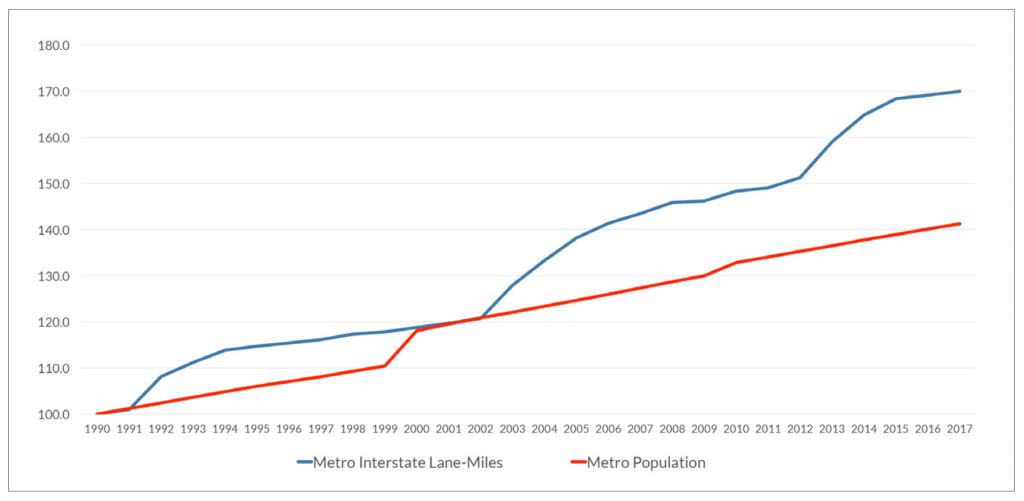

As local and state tax revenues cratered during the recession of 2008-2009, transit agencies were forced to make enormous cuts to service and lay off thousands of employees, which had devastating impacts on riders and communities. T4America covered the massive impacts across the country as millions of people were left stranded in the wake of these massive cuts. As just one example, MARTA in Atlanta eliminated somewhere around half of their bus service and train headways grew to 30 minutes at certain times of day. Even after the crisis, MARTA spent the better part of the decade recovering and slowly adding that lost service back, with little assistance from the federal government—as did hundreds or thousands of other transit agencies.

Heeding public health officials’ advice, including “social distancing,” is critical to slowing the spread of COVID-19 cases. But these essential practices also will bring unfortunate side effects: cancelled events, new work from home policies, and other ways of practicing social distancing will result in millions of transit trips not taken and profoundly affect transit agencies’ viability. Revenue from riders makes up a huge piece of transit agencies’ budgets, and transit ridership will drop across the country. At the same time, transit agencies are investing in extra cleaning supplies and increased cleaning protocols, leading to increased costs which exacerbate the budgetary pressure from reduced ridership and revenue.

The novel coronavirus will undoubtedly bring massive economic impacts on transit. If what happened in 2009 and 2010 repeats itself and Congress fails to take proper action, we will leave millions stranded without access to healthcare and other essential services, and not just in the short-term. Public transit service is and will continue to be vital and Congress must take strong action to support transit service—and ensure that transit will be robust and ready when this crisis is over.

We understand that this is a challenging time for all, and many sectors of our economy are in need of support. But we must ensure that investments made in transportation are targeted to the most impacted and most critical sectors, including public transportation. This will better address our needs today, and prepare our system for when this public health crisis subsides. Policymakers should consider these principles when developing transportation policy as economic stimulus.

1. Target funding to hardest hit transit agencies.

This is not a spread-the-peanut-butter exercise. Regions are going to be impacted in different ways, with some losing ridership to a much greater extent than others. Assistance should be appropriately targeted to the various needs of transit agencies. Sending more money to all transit agencies through the existing program is not targeted in this way and is not sufficient to address this problem.

2. Support transit agencies with operational assistance to avert service cuts or fare increases.

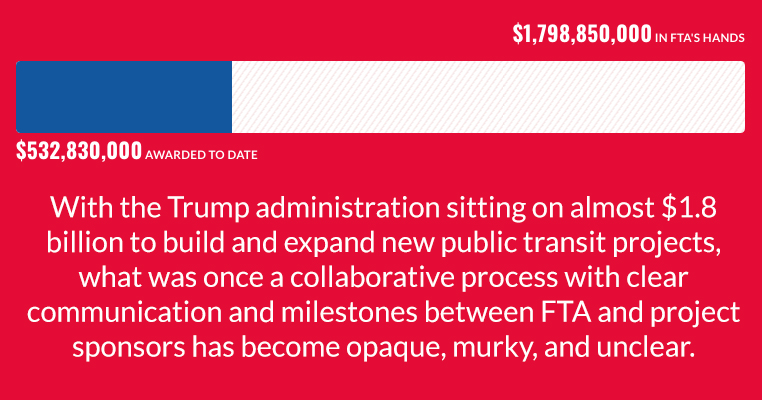

In the last recovery act in 2009, additional transit funding was given for capital investment. During this crisis, it will be necessary to invest in public transit operations to ensure agencies are able to continue providing their essential services, especially to those who rely on it to reach medical services, and health care workers who rely on it to get to work. It won’t do any good to keep giving transit agencies money to buy new buses or railcars if they can’t afford to run them each day from A to B. Transit agencies will need money to preserve service.

Agencies receive money each year from the highway trust fund, dictated by federal formulas. But those funds are for capital spending, not operating. Current law (49 USC 5307) prohibits the use of these dollars for operational expenses in communities over 200,000 in population and therefore cannot address the loss of funds at the farebox used to fund transit operations in our larger metro areas where transit provides the greatest number of rides.

3. Prioritize investments which address equity and access.

While loss of transit service is always an inconvenience, to those who depend on transit with no other option it can be particularly dangerous at this time. Those who rely on transit to reach medical care need to know that service will be there. And getting everyone who needs medical care to it early is essential to prevent a greater spread of this virus. In addition, there are scores of healthcare workers who will continue to need reliable transit service to get to their jobs caring for the sick.

While we encourage policymakers to consider these principles, we recommend the following specific policies to support public transit agencies and riders:

Responding to the immediate crisis:

- Provide targeted funding for transit operating expenses. This should address revenue shortfalls as a result of lost ridership, as well as increased expenses due to more cleaning. Funding should be targeted to those agencies with the most demonstrated need.

- Provide additional funding for purchasing personal protective equipment (PPE) (including gloves, antibacterial sanitizer, soap, etc).

- Provide funding necessary to cover costs for employees who must be quarantined, and any overtime necessary to make up for reduced numbers of employees.

Sustaining essential service beyond the crisis:

Traditional funding formulas are based on previous year ridership. If ridership were to go down this year, that could not only impact current budgets, but it would reduce what agencies receive through their formulas for next year.

- To protect impacted agencies from future cuts, Congress should create a hold harmless provision, or direct the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) to use ridership numbers from a year previous to the crisis.