This past Sunday, four presidential candidates gathered in Las Vegas to talk about infrastructure. It was a rare opportunity to ask the politicians vying for our nation’s top office critical questions—and the moderators completely blew it.

It could have been great. But it was not.

This past weekend, Pete Buttigieg, Amy Klobuchar, Joe Biden, and Tom Steyer took to the stage at the University of Nevada for the Infrastructure Forum, an event organized by United for Infrastructure and a suite of transportation unions and associations. This wasn’t the first forum of the race focused on a specific issue, but it was the first—and so far the only planned—forum focused on infrastructure. We are grateful that United for Infrastructure took up the mantle to make it happen.

The word “infrastructure” comes up in many presidential candidates’ stump speeches, but the mention doesn’t go much further than the need to “build it.” We were looking forward to hearing more about candidates’ transportation goals and the policies they would propose to get us there. (We submitted a ton of questions to the forum—thank you to United for Infrastructure for soliciting questions—but we especially wanted the candidates to answer these three.)

The billions we spend are not fixing transportation. Money isn’t the problem.

It's time presidential candidates answered policy questions at the #UnitedforInfrastructure forum. Here are ours:

What are yours? Add them by quote-tweeting our tweet! pic.twitter.com/gzP71o5NWY

— Transportation for America (@T4America) February 13, 2020

Unfortunately, Infrastructure Forum moderators failed to ask anything of substance. Our questions about maintenance, safety, and access were absent as were any meaty questions about the candidates’ plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector. Instead of asking probing questions on these issues, the Wall Street Journal reporters who moderated the forum wanted to know what superficial fixes candidates would make to address the problems our broken federal transportation policy causes—and candidates largely kept their answers superficial.

For example: the moderators asked every candidate if they would “prioritize maintaining the existing infrastructure or build a new, green transportation system.” The focus on fixing our infrastructure before building anything new is good (it’s the first of our three principles for transportation policy), but this framing presents a false dichotomy. As we found in our report Repair Priorities, states often build new highways or widen existing ones with federal transportation funding instead of maintaining existing roadways. Increasing roadway capacity actually makes traffic worse, increasing driving and emissions. Maintaining our existing roadways is a step towards a new, green transportation system: maintenance and reduced emissions can go hand in hand. Unless this was meant to be a trick question, the moderators failed here.

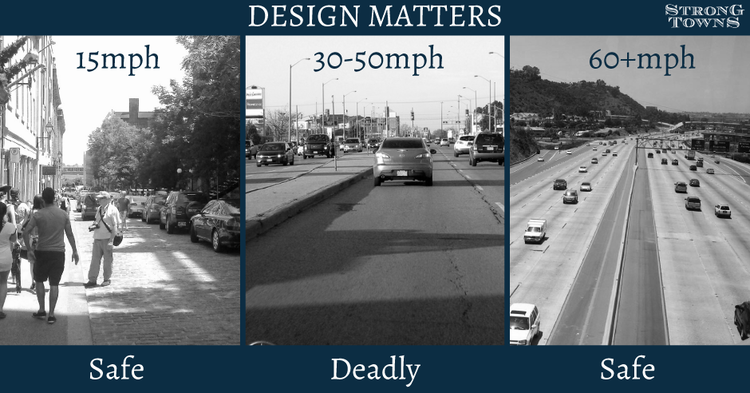

But at least maintenance got mentioned. Our other two principles—prioritizing safety over speed and connecting people to jobs and services (two things our transportation program currently does not do)—did not come up at all in moderators’ questions or candidates’ answers.

To their credit, the moderators did ask about climate change, but not about addressing climate in any meaningful way. As we know, federal transportation policy itself guarantees increasing greenhouse gas emissions by blindly pouring money into new roads, but if you didn’t already know that you certainly didn’t learn it watching this forum. Any transportation policy meant to reduce emissions has to reduce driving—but the moderators kept their questioning and candidates kept their answers to what kinds of electric vehicle subsidies they would propose, and if they “believe” in rail. (What is there to believe? Rail exists!)

Another frustrating line of questioning: The moderators kept asking candidates how they would pay for their infrastructure proposals before asking what they’re even proposing. This is more than just our pet peeve—it’s why we’re no longer advocating for Congress to increase transportation funding. On what other issues are people told the price before they know what they’re buying? (It’s not just us. Polling from the infrastructure campaign Build Together found that 63 percent of voters believe that the federal governments’ lack of vision for infrastructure policy is a bigger problem than the amount spent on infrastructure.)

It's only 10 minutes in, and @JoeBiden has already been asked how to pay for his infrastructure proposal.

We haven't even talked about what's in his proposal. #MovingAmericaForward

— Transportation for America (@T4America) February 16, 2020

Lackluster questions breed lackluster answers, but the candidates offered at least some insight into their proposals. Buttigieg was the only candidate that said the baseline transportation program needs to change, while Klobuchar and Biden think money is infinite and priorities unnecessary. Steyer—the self-professed “climate candidate”—wants to fight climate change by bringing back Cash for Clunkers, and, well, we hate to break it to him, but that won’t be enough to reduce our emissions.

We need a second Infrastructure Forum. One where candidates are actually asked how their infrastructure proposals align with their goals for the country, because “infrastructure” doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Infrastructure determines where you work, how healthy you are, and what your children can achieve. Infrastructure determines your quality of life. It’s time we asked presidential candidates real questions about it.

In case you missed it: we scored every leading presidential candidates’ infrastructure proposal on how well they achieve our three principles for transportation policy. Check it out here!

Rep. Garcia echoed this sentiment, saying, “It boils down to social justice. People cannot afford to get to where they need to go or stay where they grew up. We need to take a step back and start thinking about what it is we’re throwing hundreds of billions of dollars [at] every year.”

Rep. Garcia echoed this sentiment, saying, “It boils down to social justice. People cannot afford to get to where they need to go or stay where they grew up. We need to take a step back and start thinking about what it is we’re throwing hundreds of billions of dollars [at] every year.”