The predicted traffic levels on which transportation planners base their decisions are erroneous and rooted in obsolete methods. Here’s how transportation models fail to accurately predict future traffic, and how you can call out their misuse.

You’ve seen it before. A state DOT claims they must widen a highway through your community to reduce congestion and accommodate future traffic. The transportation agency points to traffic projections that we all take at face value. They might even claim that widening the highway will improve traffic flow thereby reducing emissions. You don’t want the highway widening in your community, but what can you do in the face of experts saying it is necessary and pointing to data that “proves” their case?

Transportation agencies use transportation models to predict future traffic and plan the roadway system accordingly. But the underlying algorithm for these models was developed in the 1980s when the computers in use were less powerful than today’s smartphones. Due to this past limitation in computing power, travel demand models use a simplified approach that doesn’t accurately represent how people make travel decisions.

T4America experts collaborated with our partners to look inside the black box of transportation models (also sometimes called travel demand models or traffic models). We submitted a memo to the US Department of Transportation asking them to apply more accountability to agencies using these models to correct them.

Some of the transportation models’ specific flaws

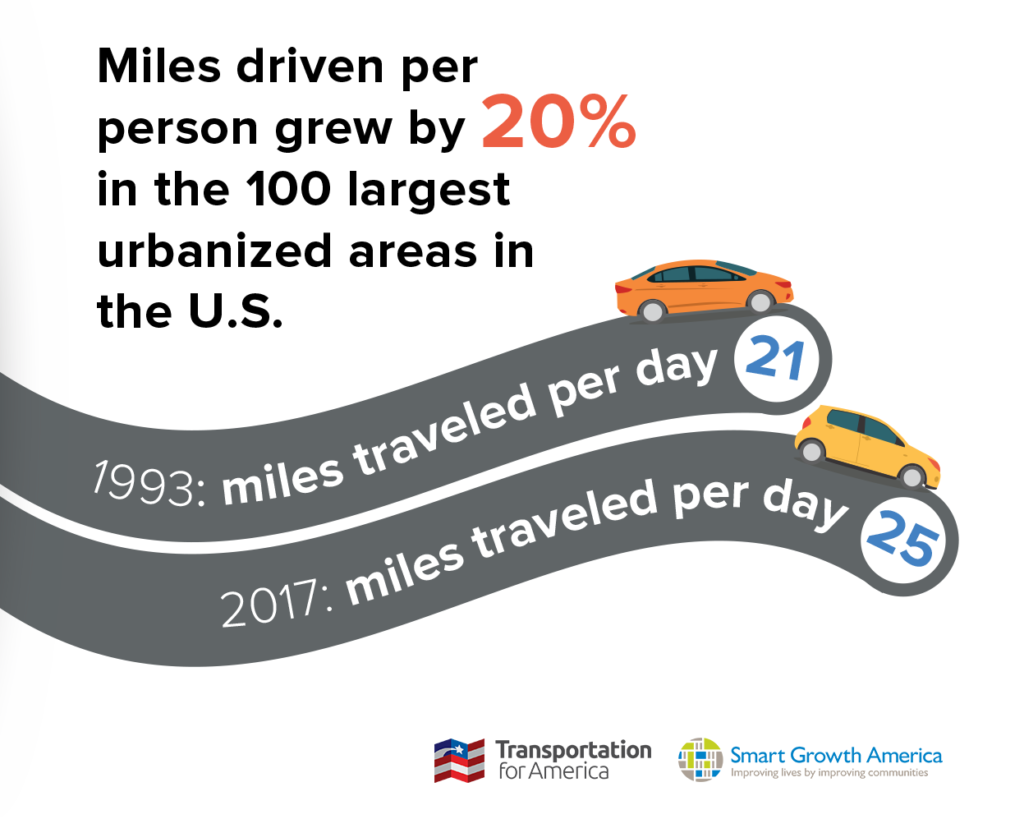

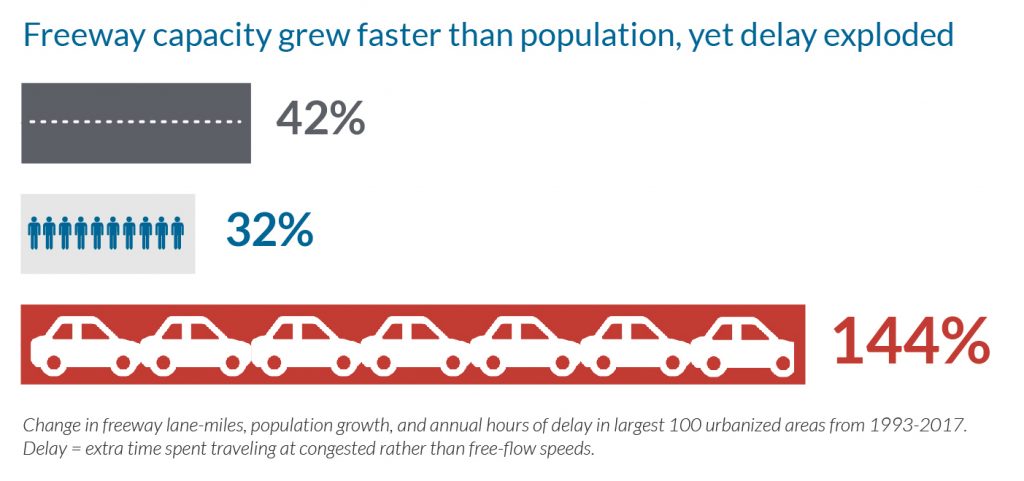

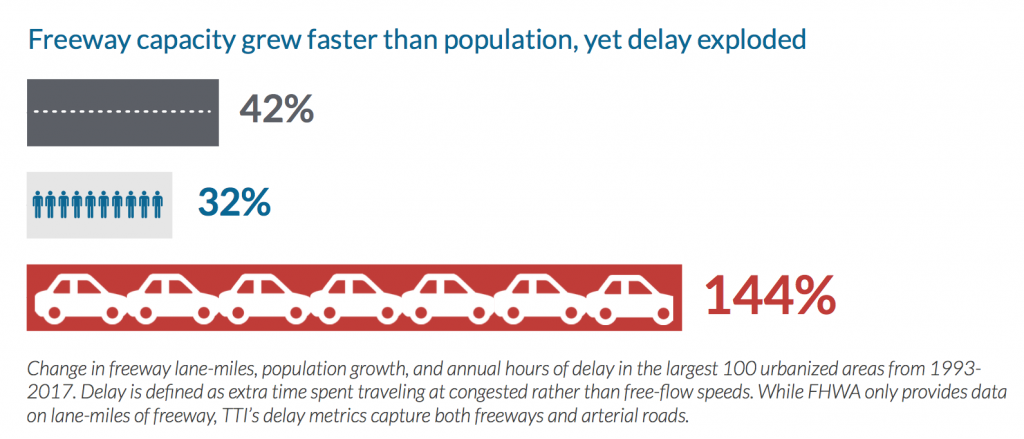

The proof that transportation models are failing us is plain to see in the long term trends. Over the last 20 years, congestion has increased in every single U.S. metropolitan area regardless of how much they’ve expanded their highways and regardless of whether their population grew or shrank.

In what way have transportation models misled us? It largely has to do with the underlying approach which is too simple, chosen because of limited 1980s computing power. Transportation models use a Static Traffic Assignment (STA) algorithm which is a sort of snapshot in time of how much traffic is on each roadway in a region at a given moment. This static algorithm is problematic, since people make decisions on different factors every day, often in the moment. People are dynamic not static.

What’s more, STAs do not properly account for bottlenecks, or constrain forecasts based on roadway capacity. No roadway can ever carry more cars than its maximum capacity, any more than a coffee mug can hold 110% of its coffee capacity. Yet agencies routinely and confidently make claims like, “without this expansion, the roadway will be at 110% capacity.” If you point out that a roadway can’t handle more cars than it has capacity for, they say that extra 10 percent is “latent demand.” In other words, they are certain that there’s exactly 10 percent more cars and trips out there that must be served.

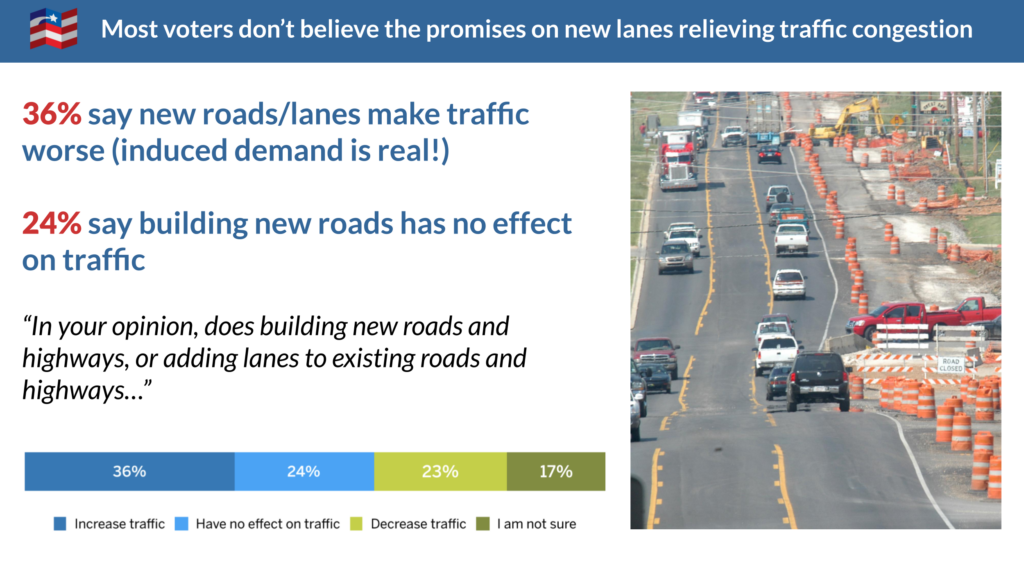

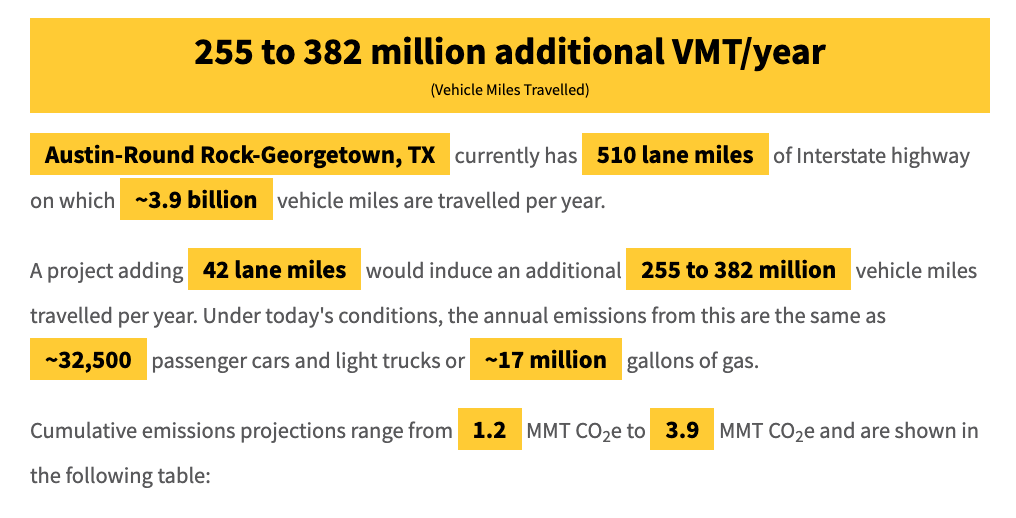

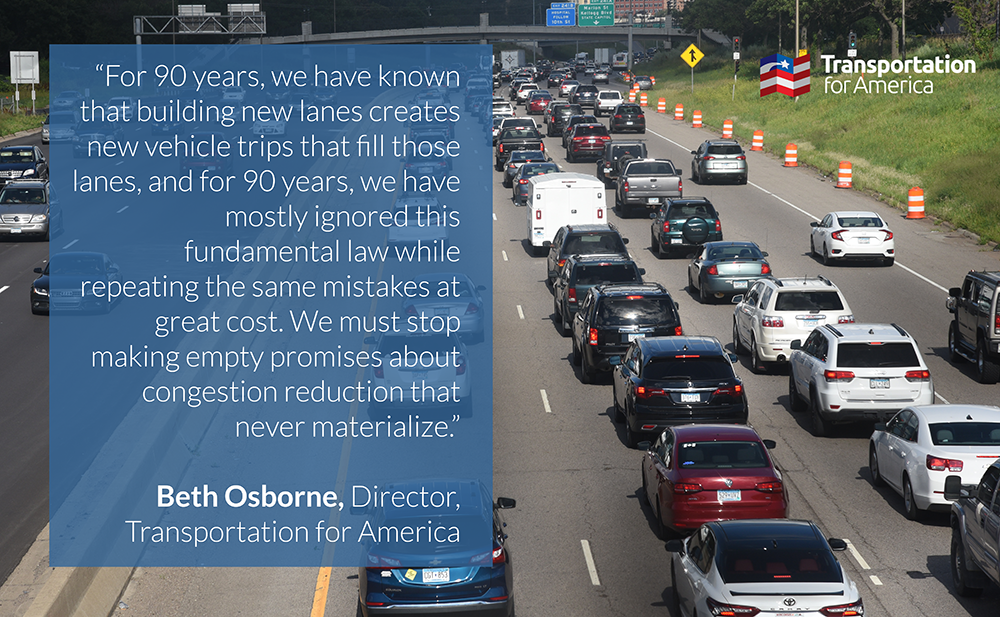

We call this induced demand—demand created by the new road itself—a concept those same agencies often claim doesn’t exist. (But which the public absolutely understands, as our brand new national polling shows.) By trying to sell the project on all that “latent” demand, they can claim a traffic nightmare if nothing is done without admitting that the project will actually create more traffic—and more greenhouse gas emissions, fine particulates, etc. [USDOT and the Environmental Protection Agency support that approach for some unfathomable reason, never asking if the models used to justify federally funded projects have been right.]

In reality, as congestion increases toward that 100% capacity mark, people make different travel decisions, change their routes, choose to travel at a different time, use a different mode or choose a closer destination to fulfill the same need. If there is a crash, people delay their trip or consult Google maps and choose a different route. But transportation models using the STA approach unrealistically assume people will blindly keep driving a congested roadway, no matter what is happening or how long their trip will take.

Not only does the model assume no changes in behavior, but it will also output results that show drivers stuck at one bottleneck, while simultaneously allowing them to magically pass through that one to also be stuck at another bottleneck downstream.

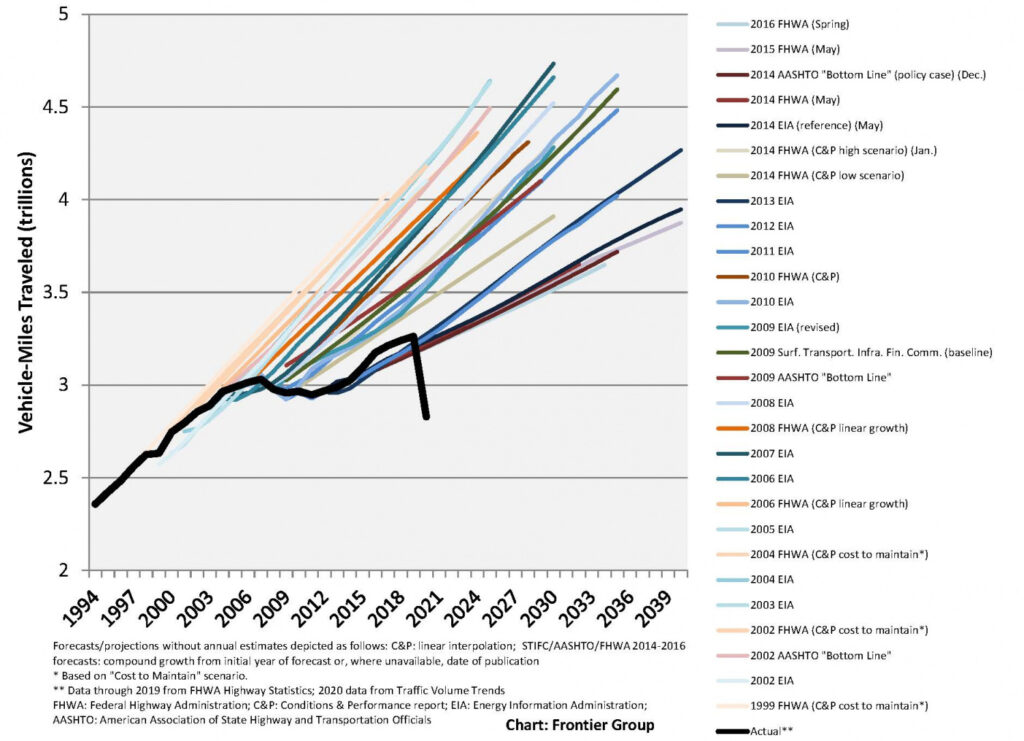

Compounding these issues, planners rarely, if ever, look back at their past work to see if their predictions were correct. Did the traffic materialize? We’re stuck with decades-old models that are never tested or upgraded to reflect reality, as shown here:

How to question your region’s model

We’re hopeful that USDOT will eventually provide accountability to upgrade the state of practice on transportation modeling, but you can also ask questions about the transportation models used to promote road widenings in your community. Here are some things you can ask your local transportation planners to illustrate the flaws of using transportation model results to justify road widenings:

- Does your model use Static Traffic Assignment?

- What is the maximum volume to capacity in your model runs, and how is that realistic? (If they give a volume over 100%, ask how a road can carry more than its capacity. And ask if latent demand will fill the new capacity they are building then what good will this investment do?)

- How does your model account for dynamic changes in commuting patterns, responses to crashes, or the threshold at which people shift to other modes?

- What is your protocol for evaluating the accuracy of your past traffic projections and using that to improve upon the model? Where is it published?

Getting our transportation models to better reflect reality will help planners make better decisions about where to invest our tax dollars. Calling on USDOT to upgrade standards for transportation models, and calling out their misuse locally in the meantime will help us turn the corner to more sensible improvements to transportation in our nation.