House transportation leaders introduced legislation to update our national transportation program to address climate, equity, safety and public health. Climate advocates and climate leaders on the Hill should recognize the strides taken with this proposal from Congress and fight to protect those changes in the bill.

This is a joint post by Transportation for America and Third Way, co-written by Rayla Bellis, T4America program manager, and Alexander Laska, Third Way Transportation Policy Advisor for the Climate and Energy Program. It is also posted on Third Way’s site.

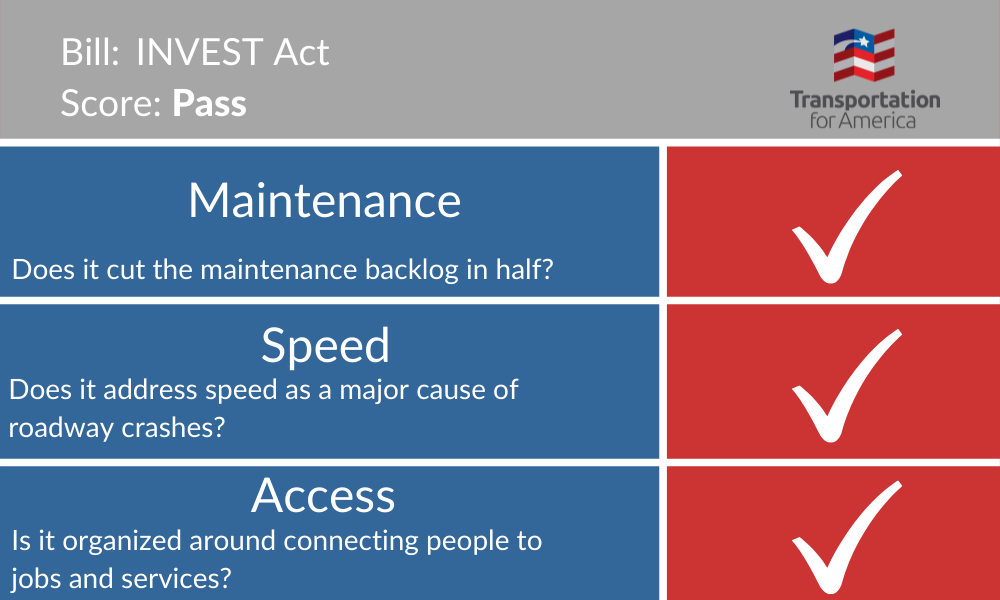

While it isn’t perfect, the INVEST Act introduced in the House takes some very important steps, including:

- Measuring and tracking important outcomes like GHG emissions and access to jobs and services.

- Making significant progress towards electrifying our vehicle and transit fleets; and

- Supporting investments in low emissions transportation modes, including:

- Supporting transit with more money and better policy; and

- Supporting biking and walking with a comprehensive approach to improving safety.

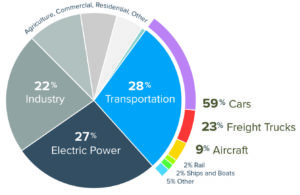

For too long, federal transportation policy has prioritized car travel and the infrastructure to support it while neglecting cleaner and more affordable transportation options like transit, walking, and biking. We are now seeing the consequences of decades of spending in line with those priorities: car-ownership is a prerequisite for participating in the economy in most communities, and many people are driving further every year to reach work and daily necessities. It is unsafe, inconvenient, or flat-out impossible to reach those destinations by any other means in much of the country. As a result, transportation is now the nation’s single largest source of greenhouse gases (GHG), accounting for 29 percent of emissions, 83 percent of which comes from driving. While cars and trucks will and should remain an important part of our transportation system, any effective strategy to reduce emissions from transportation must make it easier for Americans to take fewer and shorter car trips to access work and meet basic needs.

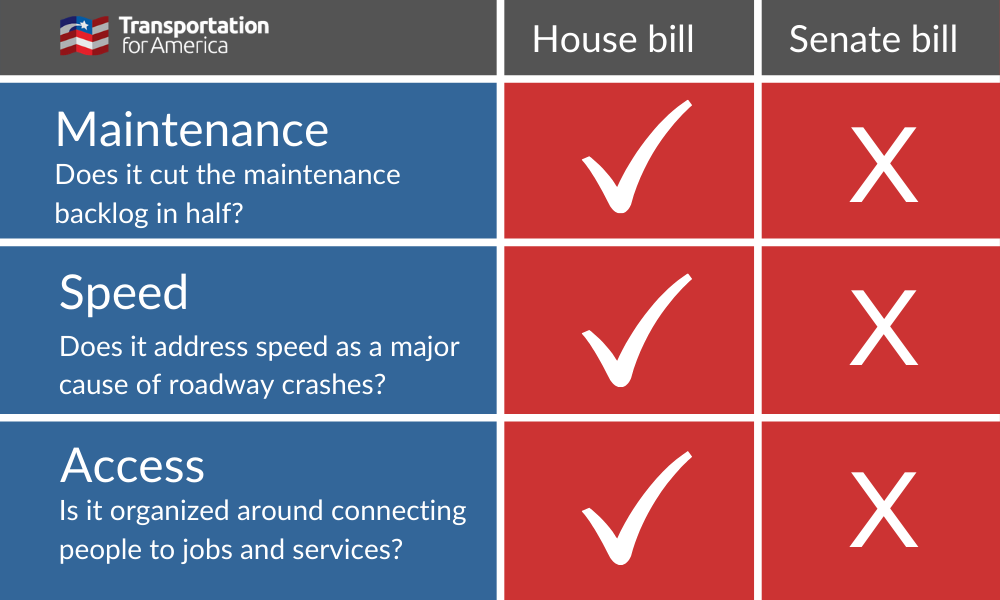

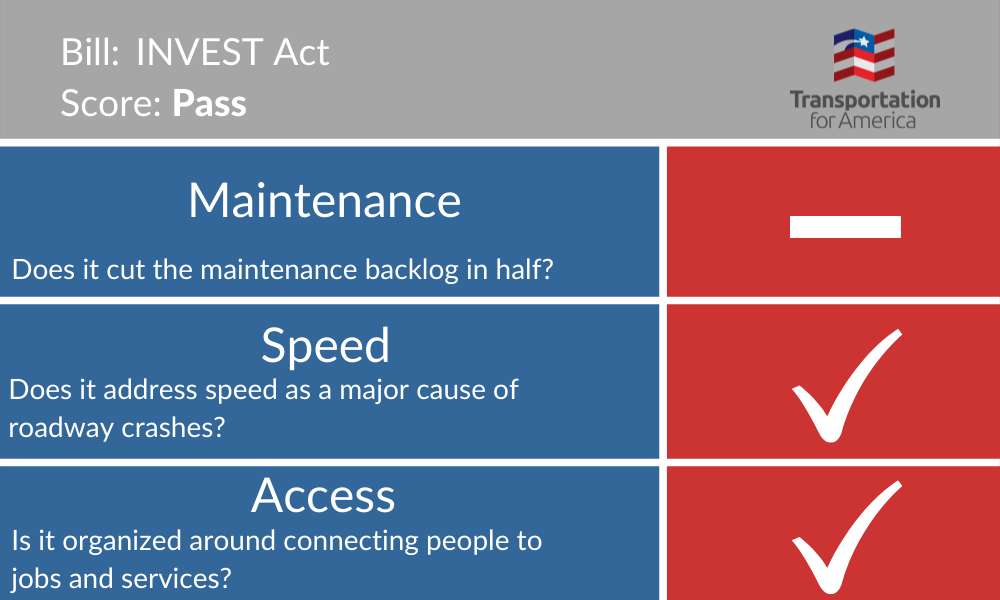

Last week the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee released their transportation reauthorization proposal. Third Way and Transportation for America unveiled a scorecard earlier this week to show how the new House reauthorization proposal and previous Senate proposal stack up against the recommendations in our new Transportation and Climate Federal Policy Agenda. The House bill makes significant strides in several areas in line with our federal policy agenda:

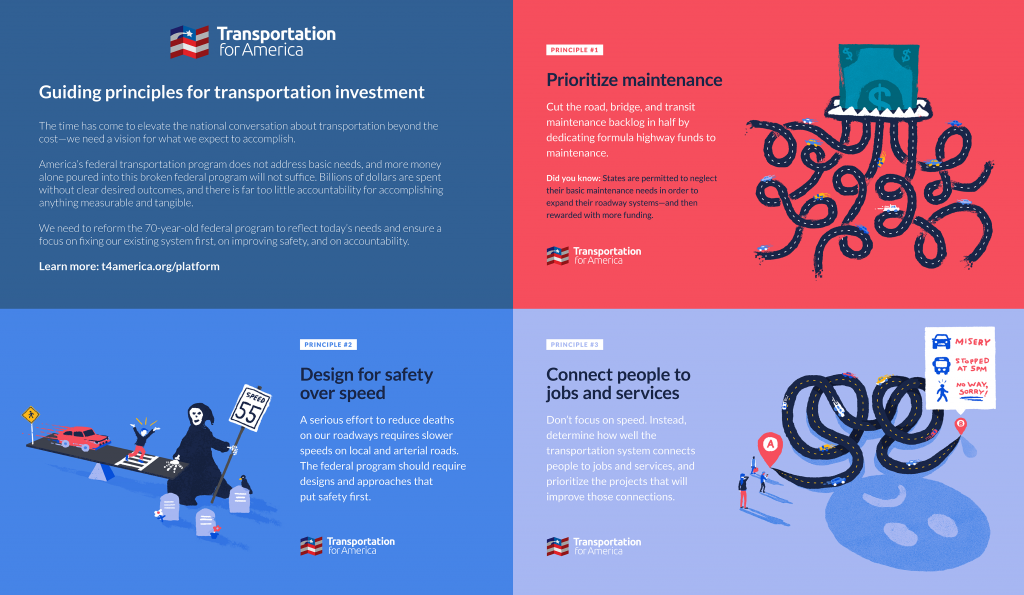

Measures and tracks important outcomes

We measure all the wrong things in our transportation system and therefore get the wrong outcomes. Instead of measuring whether people can get where they need to go (e.g., jobs, healthcare, and grocery stores), we measure how fast cars are moving. Rather than being required to reduce transportation emissions, states are distributed more money if their residents drive more and burn more gasoline.

The House bill takes important steps in reversing these perverse incentives. It requires states to measure and reduce greenhouse gas emissions from their transportation system (a similar requirement from USDOT was rolled back early in the Trump administration). States that reduce emissions can be rewarded with increased flexibility, while states that fail to reduce emissions will face penalties. This is a major shift, and it will lead to significantly different outcomes if states are truly held accountable to these requirements.

In addition, the bill requires a new performance measure to help states and MPOs evaluate how well their transportation systems provide access to jobs and services. This access measure is monumental. For the first time at the national level, recipients of federal transportation funding will be required to measure whether their transportation system is performing its most essential function: connecting people to the things they need, whether they drive, take transit, walk or bike. This will have profound impacts in communities, including directing more funds to projects that shorten or eliminate the need for driving trips. It also happens that providing a high level of access, especially for nondrivers, correlates with lower GHG emissions.

Makes significant progress towards electrification

Decarbonizing our transportation system will require us to transition quickly to zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs)–and that means making sure we have the infrastructure ready to support those vehicles. The INVEST In America Act establishes a new $1.4 billion program to deploy electric vehicle charging and hydrogen fueling infrastructure in public places where everyone will have access. The grant program will focus on projects that demonstrate the most effective emissions reductions. We believe the program should additionally focus on ensuring this infrastructure is accessible to low-income communities; this, combined with policies to make ZEVs more affordable, will help ensure all Americans can benefit from the air quality improvements and other benefits of clean vehicles.

The bill also reorients federal funding for transit buses towards electric vehicles by boosting funds for the Low- and No-Emission Vehicle Program five-fold, incentivizing the purchase of electric fleets, and requiring a plan for transitioning to a 100 percent electric bus fleet. This improved program, and other transit reforms, will help transit agencies procure electric and other clean buses, as well as the refueling infrastructure to support them. Transit is already a lower-carbon alternative to driving, and shifting our fleet towards clean buses will make it even more so. Ultimately, all federal funding for bus procurement should go towards low- and no-emission buses, but the significant increase for this program is a good start.

Supports transit with more money and better policy

Too many Americans must drive because they either are not served by transit or only have access to infrequent, unreliable, and inconvenient service. Transit has been underfunded for decades at the federal level despite the significant benefits it provides to communities: reduced emissions, improved economic opportunity, a way out of congestion, cleaner air, mobility choice, better health outcomes, and improved quality of life. Our failure to invest sufficiently in transit has disproportionately impacted low-income people and people of color, who are more likely to rely on transit to access jobs and services.

The House bill gives transit a big increase in overall funding: 47 percent. Equally importantly, however, it changes some policies that have long obstructed transit as a truly viable option in communities. For years, federal transit funding has incentivized lowering operating costs (usually accomplished by offering less or infrequent service) at the expense of building transit that best serves people’s needs. The new bill includes policies that shift those incentives, focusing instead on frequency of service. This will make transit a real option for more people in more communities.

Supports biking and walking with a comprehensive approach to improving safety

Dangerous road conditions pose one of the biggest barriers to taking short trips by walking or biking in many communities, leading to unnecessary driving trips that increase traffic and emissions. Between 2008 and 2017, drivers struck and killed 49,340 people walking on streets nationwide, and pedestrian fatalities have risen by 35 percent over the past decade. People of color, older adults and people walking in low-income communities are disproportionately represented in these fatal crashes.

The House proposal takes a comprehensive approach to make walking and biking safer through a combination of increased funding, policy reform, and better provisions to hold states accountable. For example:

- The bill requires Complete Street design principles and makes $250 million available for active transportation projects including Complete Streets.

- It proposes changes to how speed limits are set to prioritize safety results over a faster auto trip.

- It requires states with the highest levels of pedestrian and bicyclist fatalities to set aside funds to address those needs.

- The bill would also prohibit states from the current practice of setting annual targets for roadway fatalities that are negative—in other words, targets that assume the current trend line of increased fatalities is unstoppable, essentially accepting more fatalities every year as an unavoidable cost.

The House bill isn’t perfect, but is a significant improvement over the Senate’s proposal

While the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee’s proposal takes many steps in the right direction, it still misses the mark in some areas based on our agenda. It still includes significant funding for highways without the proper restrictions in place to avoid unnecessary buildout of new lane-miles we can’t afford to maintain, and congestion relief is still a primary goal embedded throughout the proposed program. This ultimately prioritizes the same types of transportation investments we have seen for decades.

Yet, the House bill takes significant steps that the Senate EPW bill introduced last year did not. In contrast to the broad, holistic approach the House bill takes to addressing emissions, the Senate bill introduced some new (but relatively weak) stand-alone programs to address emissions, congestion, and other important topics. Importantly, the Senate bill did not make any needed changes to the core federal formula programs, continuing to direct the vast majority of funding into programs that incentivize building high-speed roads and making travel by any means other than driving — and emitting — impossible for most Americans.

Bottom line: the House’s proposal could be a game-changer for climate, equity, and safety goals

The House’s proposal introduces more substantial reforms to our national transportation program than we have seen in years, and many of the changes will directly support reduced emissions, environmental justice, and other important goals. This is a big deal, but the magnitude of the changes may not be readily apparent. Many of the most transformative proposals do not sound like climate initiatives because they do not specifically reference emissions or address electrification. Instead they change funding formulas, policies, and performance measures that, over decades, have produced a transportation system that requires more and longer car trips and greater emissions.

Climate advocates and climate leaders on the Hill should recognize the strides taken with this proposal from Congress and fight to protect those changes in the bill. Advocates for preserving the status quo are preparing to fight these important changes. We need climate advocates to do the same to defend them.

We won’t be able to increase fuel efficiency and electrify cars faster than VMT is rising, reducing the impact of electrification particularly in the next 10-20 years. And VMT is rising because the current federal transportation program—the broken program that the Senate is proposing to effectively renew with more money for five years—

We won’t be able to increase fuel efficiency and electrify cars faster than VMT is rising, reducing the impact of electrification particularly in the next 10-20 years. And VMT is rising because the current federal transportation program—the broken program that the Senate is proposing to effectively renew with more money for five years—

It’s time for Democrats and Republicans—and more of the press—to think about what a transportation program can and should achieve: access to jobs for rich and poor, a safe travel environment for those in and out of a car, and a well-maintained system. None of these goals are partisan. Democrats and Republicans may come to each priority for slightly different reasons, but there is a new bipartisanship that can emerge around creating a better transportation system if we just look at what we are building and not just how much we can build.

It’s time for Democrats and Republicans—and more of the press—to think about what a transportation program can and should achieve: access to jobs for rich and poor, a safe travel environment for those in and out of a car, and a well-maintained system. None of these goals are partisan. Democrats and Republicans may come to each priority for slightly different reasons, but there is a new bipartisanship that can emerge around creating a better transportation system if we just look at what we are building and not just how much we can build.