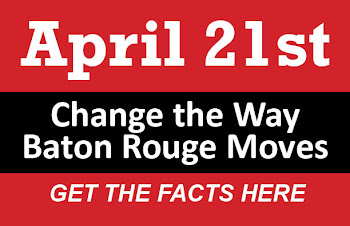

Last month, the citizens of Baton Rouge, LA, voted to raise their taxes to preserve and expand their struggling bus system. The landmark measure will nearly double transit funding — saving the system from meltdown while laying the groundwork for dramatically improved service.

To pass it, churches, faith-based groups and local organizers teamed up with businesses and institutions. As we’ve seen in similar local measures, they won by explaining exactly what taxpayer money would buy, building a diverse coalition and getting out the vote.

This in-depth story is part of our Transportation Vote 2012 coverage. Communities across the country are preparing to vote on the people, plans and projects that will set the tone for transportation progress in the months and years to come. These are the places that will provide the energy, innovation and inspiration for the next national vision for transportation. Transportation Vote 2012 will help educate voters, advocates and candidates and keep abreast of transportation-related issues as they unfold.

A crisis point

Even before the prolonged fiscal crisis hitting governments everywhere, Baton Rouge’s Capital Area Transit System (CATS) struggled to do more with less. Over the last few years, service had degraded to the point that the wait for a bus exceeded 75 minutes and average rides were over two hours long. The system was saved repeatedly only by last-ditch city budget shuffles, creative grants and even private donations.

The biggest recent blow came when Louisiana State University backed out of the CATS system after years of student complaints and contracted with a new (more expensive) private operator. That meant a loss of $2.4 million from the CATS annual budget.

In 2010, a parish-wide tax to support the transit system failed at the ballot box, in part because large parts of the parish (same as counties in other states) don’t use or have access to the service. When projections came in that the transit agency would be so far in the red they’d have to shut down in summer 2011, it became painfully clear that something major needed to be done.

After cobbling together grants and funding to make it through 2011, the mayor appointed a Blue Ribbon Commission to make recommendations not only to save the service, but to create something much better. But the first job was to save the system, as Rev. Raymond Jetson, the chair of that commission, told the Baton Rouge Advocate: “Before there can be a robust transit system, before you can do novel things like light rail between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, and before you can have street cars from downtown to LSU, you have to have a backbone to the system,” he said. “And that backbone is a quality bus system.”

The commission learned that Baton Rouge was the largest city of its size in the country to have a transit system without a dedicated revenue source, subsisting on annual local government appropriations.

But before putting a funding measure to voters, the commission recommended significant reforms to the composition of the transit board and an end to the ability of the Metro Council to veto the board’s decisions. “Governance reform and long term accountability … helped separate it from the previous failed measures,” said Broderick Bagert of Together Baton Rouge, a broad, multi-racial, faith-based coalition of institutions backing the measure.

Photo courtesy of Frank McMains, www.frankmcmains.com

So how did they do it?

Coalition building

The first step was to build the core coalition that would push this measure to victory.

Enter Together Baton Rouge, a relatively new organization of churches, faith-based groups, social workers, and university students and groups. Together Baton Rouge led the way as the grassroots behind the measure, coordinating call banks, get-out-the-vote rallies, more than 120 educational “transit academies” and door-to-door canvassing of tens of thousands of homes by hundreds of volunteers. (Note that LSU students chose to get actively involved even though CATS was no longer the provider of their transit service on campus.)

They began with three informational meetings with 300-400 people each, where “community members told other community members why things were bad and what the new plan was,” said Bagert.

“We asked two questions on the sign-in card: ‘Do you want to be part of a voter outreach campaign?’ and, ‘Are you part of an organization and would you be willing to organize one of these sessions?’ We built a strong base of people that wanted to help do outreach and educate their fellow community members.”

Photo courtesy of Together Baton Rouge

In part because of the groundwork of the Blue Ribbon Commission and other partnerships, the Baton Rouge Area Chamber got on board along with other business groups. Hotels and hospitals, whose leaders realized how much of their workforce depended on CATS each day, joined in.

Colletta Barrett, vice president of missions for Our Lady of the Lake hospital system told the Advocate that 10 percent of OLOL’s staff, or 400 people, use CATS.

It is imperative, she said, that a transit system is available to move people from North Baton Rouge to the medical corridor in the southern part of the parish.“It’s unacceptable that it takes an hour and 45 minutes to get to this side of town,” she said. “We have told our employees that we have an individual social responsibility to take care of each other.”

And:

Ralph Ney, hotel general manager for Embassy Suites [hotel], said about 15 percent of his workforce uses CATS to get to work, which sometimes results in his employees being late.

“It’s difficult to hire and maintain employees who don’t have transportation,” said Ney, who was a member of the Blue Ribbon Commission. “It’s evolved to where a lot of our employees don’t even take the bus because they can’t get to work on time, so they’re riding bikes or catching rides.”

A key part of the coalition was the Center for Planning Excellence (CPEX), a T4 America partner and non-profit that helps Louisiana communities with planning issues and addressing complex problems with effective, forward-thinking, implementable solutions. They became involved through their CONNECT initiative to build a diverse coalition across the New Orleans to Baton Rouge super region to advocate for smarter housing and transportation investments. The CONNECT initiative concluded that one of the critical pieces for regional connectivity is a viable, robust transit system serving the metro area. This was also strongly recommended in the new comprehensive plan for Baton Rouge, called FutureBR.

CPEX worked with many of the former members of the Blue Ribbon Commission to create the Baton Rouge Transit Coalition, a diverse set of partners who provided information, resources and conducted educational outreach to the Baton Rouge community. They hosted numerous outreach meetings, advocated for the changes to CATS governance in the state house, created a website that became a clearinghouse for facts and research during the campaign, and worked closely with the Baton Rouge Area Chamber to solicit support from the business community — in addition to being a strong part of the grassroots effort led primarily by Together Baton Rouge.

In the end, the boosters of the transit measure had built a coalition that had strong grassroots, wide reach, and a diverse range of interests. Without the participation of any one of the core coalition members — Together Baton Rouge’s grassroots and trusted community members, CPEX and their coalition of transit boosters and others, and the area Chamber and the business community — the effort would not have had the same success.

Trusted messengers — and message

Broderick Bagert of Together Baton Rouge summed up this strategy simply: “We let the community leaders be out front leading the way. Not professionals, not paid staff, not elected officials, not transit officials.”

Broderick Bagert of Together Baton Rouge summed up this strategy simply: “We let the community leaders be out front leading the way. Not professionals, not paid staff, not elected officials, not transit officials.”

“One of the strengths of this effort was that the plan was created by community leaders and many of the important people were already behind the plan,” said Rachel DiResto of CPEX. “It certainly took some effort to get new folks on board, but the important pillars were already on board. We didn’t need to convince them.”

For the message, especially in the key districts with heavy transit usage and service, the campaign kept it very basic. “Save our system.” They noted that Baton Rouge was the only city of its size without a decent transit system, and talked about the people who depend on it each day: Perhaps the nurse who cares for your mother at the hospital, or your neighbor or friend. The campaign steered clear of some of the typical statistics in transit campaigns about reducing traffic congestion, gas prices or environmental impacts.

The above story about the hospital and hotel workers shows how the advocates built a larger, inclusive narrative and a vision for the community’s future. The events were filled with personal stories and made the impact of the system (and the potential impacts of not having it or having it improved) clear to everyone, regardless of who they were, where they lived, or whether or not they rode CATS.

Success wasn’t due to being the smartest person in the room armed with the most data and facts. It was about making the impacts real and relatable through powerful stories helping people realize the bonds and impacts of community.

“Outreach, outreach, outreach”

To deliver that message, Together Baton Rouge and the coalition held an insanely ambitious number of community outreach sessions they called “transit academies” or “civic academies” in churches, community centers and other venues. In the four-month campaign leading up to the April 21 vote, they hosted 120 of these sessions.

“Anywhere anyone wanted to hear more, we did a presentation,” said DiResto of CPEX. “And it paid off with more people who hadn’t been active voters showing up at the polls for a special election.”

Photo courtesy of Together Baton Rouge

These meetings were largely targeted to areas and precincts where support and heavy turnout would be needed to shift the outcome of the vote. “The diversity of those meetings was a huge plus,” DiResto said. “People who would never ride CATS were sitting in the same meetings with those who ride it every day. And their stories really impacted the former.”

The Advocate told one such story, about Fred Skelton, a 70-year-old Baton Rouge homeowner who had never ridden a CATS bus before. But during one community meeting he said he would be “first in line at his voting precinct to support” the 10-year, 10.6-mill property tax. The reason, he said, is because before his mother died, she used to stay at a nursing home where he’d visit her. When he visited, he said, he remembered frequently seeing groups of employees waiting for the bus.

“Those people who were waiting for the bus are the people who were taking care of my mother,” he said. “If we shut down the transit system, who will take care of those people?”

Strategic precinct targeting

Resources are always limited in a campaign, and therefore best deployed where they can make the most impact. The overall strategy — change minds of people on the fence, increase support from typically opposed groups, or focus primarily on the base — determines where resources should be targeted.

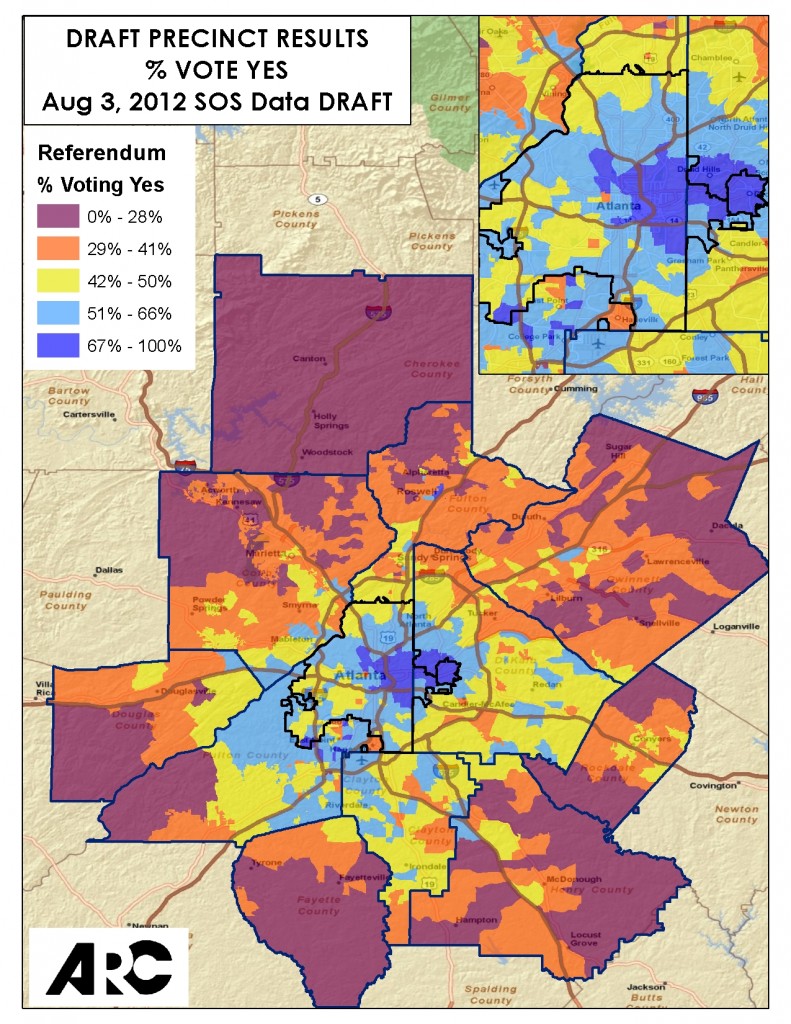

One of the biggest differences between this successful measure and the recent failed measure in 2010 was the use of more strategic targeting of resources in key precincts. Though the campaign did deploy some resources in suburban areas with small amounts of service, mostly to blunt opposition, the brunt of their efforts focused on getting out the vote in their strongest precincts.

Canvassing team. Photo courtesy of Together Baton Rouge

“We did detailed analysis of the electorate,” said Bagert of Together Baton Rouge. “We referred to the recent failed measure for background, which helped analyze the lay of the land. We focused our direct energy on turning out the strongest [most supportive] precincts, leaving out voters that had no voting history in the last 4 years. We tried to get 10 percent of the 2008 presidential election voters to vote for the measure.”

As a result of this strategy, the campaign was well poised to bounce back and succeed when The Advocate threw a curveball late in the game and editorialized against the transit tax, which likely cost the campaign a significant amount of support in precincts with already low support or people and groups that were undecided.

Making the benefits tangible and measurable

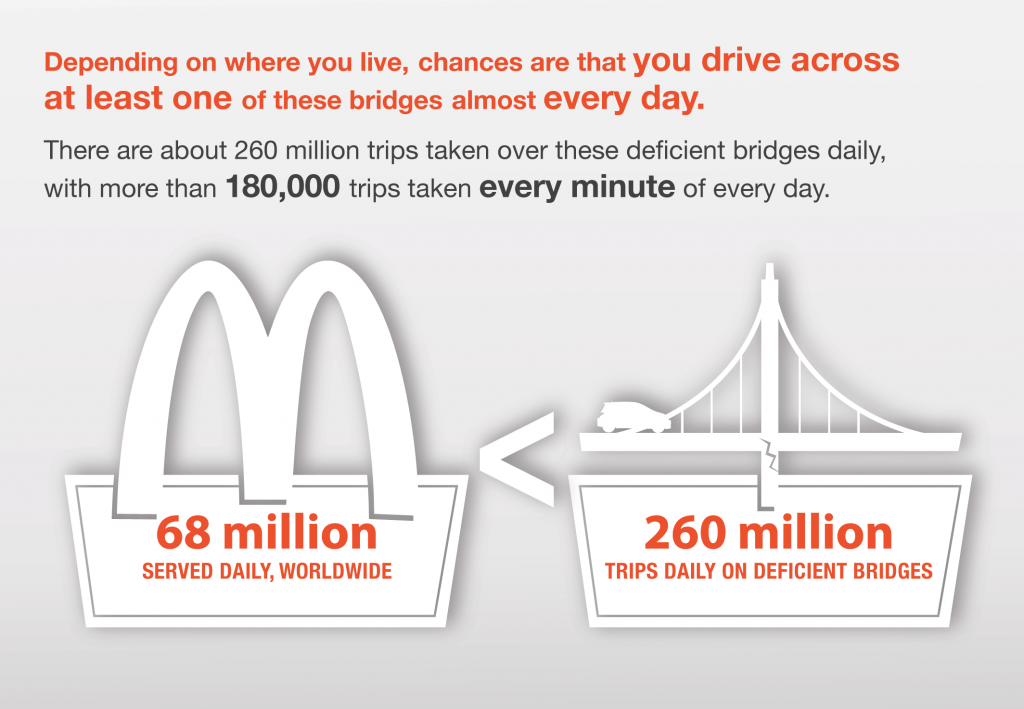

Whether it is the federal program or a local ballot measure, voters need to know what our dollars are really “buying” at the end of the day. Are they going to fix our bridges? How will they better connect workers with jobs, make their lives eaier, save them money?

On this count, the coalition in Baton Rouge did an admirable job of making this crystal clear — backed in large part by the commission recommendations that had large buy-in from day one. In every meeting they offered a list of promised CATS improvements:

CATS promises the following changes if the tax passes:

- Decreased average wait times for buses from 75 minutes to 15 minutes.

- Eight new express and limited stop lines, serving the airport, universities, mall and other areas.

- GPS tracking on the entire fleet, with exact arrival times accessible on cellphones.

- New shelters, benches and signage at bus stops.

- Expanded service to high-demand areas and increased routes, from 19 to 37.

- Three new transfer centers operating in a grid system to replace the outdated route system that leads all buses back to Florida Boulevard.

- A foundation for Bus Rapid Transit, a system in which buses get their own right-of-way lanes.

The ambitiousness of the promised changes was part of the success. Given the (somewhat unfair) perception that CATS was a poorly governed money drain, simply offering up a plan to pour money into CATS and hope for the best was not going to fly. People had to be inspired to believe that things actually would get better.

Similar specificity and transparency, including a long-range map of projects, helped win 67 percent of the vote for Measure R in Los Angeles. Supporters in Atlanta hope that a pre-approved list of transit and road projects will help convince voters to support a regional sales tax this July. The Baton Rouge formula – specific improvements, accountability reforms and relentless grassroots engagement – could offer a path to similar success.

Wrapping it up

The transit ballot measure was approved on April 21 in Baton Rouge, 54 percent to 46 percent and the municipality of Baker, 58 percent to 42 percent. In Zachary, a more suburban area with little service, it was rejected, 79 percent to 21 percent. Early returns showed the measure losing with only 40 percent support, but “then the precincts we had worked came in and voted in historic levels, supporting the measure at around 90 percent in those key precincts,” according to Bagert. “The key was really getting strong vote in supportive precincts.”

The transit ballot measure was approved on April 21 in Baton Rouge, 54 percent to 46 percent and the municipality of Baker, 58 percent to 42 percent. In Zachary, a more suburban area with little service, it was rejected, 79 percent to 21 percent. Early returns showed the measure losing with only 40 percent support, but “then the precincts we had worked came in and voted in historic levels, supporting the measure at around 90 percent in those key precincts,” according to Bagert. “The key was really getting strong vote in supportive precincts.”

The story isn’t over, however.

The governance reforms for CATS, including changing the Metro Council’s veto power, are still passing through the state legislature. (The council’s veto power over changes in fares, routes, schedules and other operations was cited by the Blue Ribbon Commission as a key factor crippling the transit system.) The board nominating process will also change so that 13 different groups that have a stake in transit system (hospitals, businesses, etc.) can nominate members to the board.

Though some groups that were opposed are considering some legal challenges to the tax itself, the Baton Rouge story shows us a great success story of how a community rallied around their important transit system, fought to save it and improve it, and built a winning campaign to do exactly that.

Advice for others

Facing a ballot measure in your area? Planning one? Here are four last smart pieces of advice to take with you from Rachel DiResto from the Center for Planning Excellence.

- Bring core partners to the table early and find your champions who have to be willing to speak well to various audiences and who are willing to expend time and energy for your cause;

- Frequent communication with other partners is critical to maximize resources and not duplicate efforts;

- Focus on the voter outcome – grassroots advocacy is essential – target those folks who are supportive and mobilize them to show up to vote instead of spending all of your energy combatting those opposed.

- Frequent outreach to different sectors – know your message for various audiences

The election day team for Mid City. Photo courtesy of Together Baton Rouge

Excited? Encouraged? Learn something that you didn’t know before? Let us know in the comments.

Our sincere thanks go out to Broderick Bagert of Together Baton Rouge and Rachel DiResto and Lacy Strohschein of the Center for Planning Excellence for their time and information for the behind-the-scenes story of their success. And also to Rebekah Allen of the Advocate, whose solid reporting on the issue for the last few years was invaluable for understanding and background, as well as the source of valuable quotes.

Follow all Transportation Vote 2012 coverage here.

.jpg)

With

With