Already standing in sharp contrast to the House’s approach to funding transportation for the next fiscal year, leaders in the Senate are working to further improve the smart Senate transportation funding bill through a handful of amendments to the bill as it reaches the floor.

With the approval by the full Senate Appropriations committee, the Senate’s yearly transportation (and housing) funding bill is now being considered on the full Senate floor.

Which means amendments…lots of amendments.

Senator Schumer (along with Sens. Gillibrand, Menendez, and Cardin) proposed an amendment (No. 1763) that would allow rail and transit bridges to also be eligible for the $500 million in the Bridges in Critical Corridors program. Our most critical corridors aren’t always just highways, and this allows states and local communities to apply for flexible funding that can meet their greatest local need, whether that a bridge carries trains or cars.

There was another predictable attempt by Senator Rand Paul to take away the tiny slices of money that local mayors and communities often use to invest in popular trails and protected bikeways like Indianapolis’ downtown Cultural Trail or Washington, D.C.’s Capital Crescent trail that commuters depend on daily and spend those relative pennies on bridge repair. (Streetsblog covered this troubling amendment yesterday.)

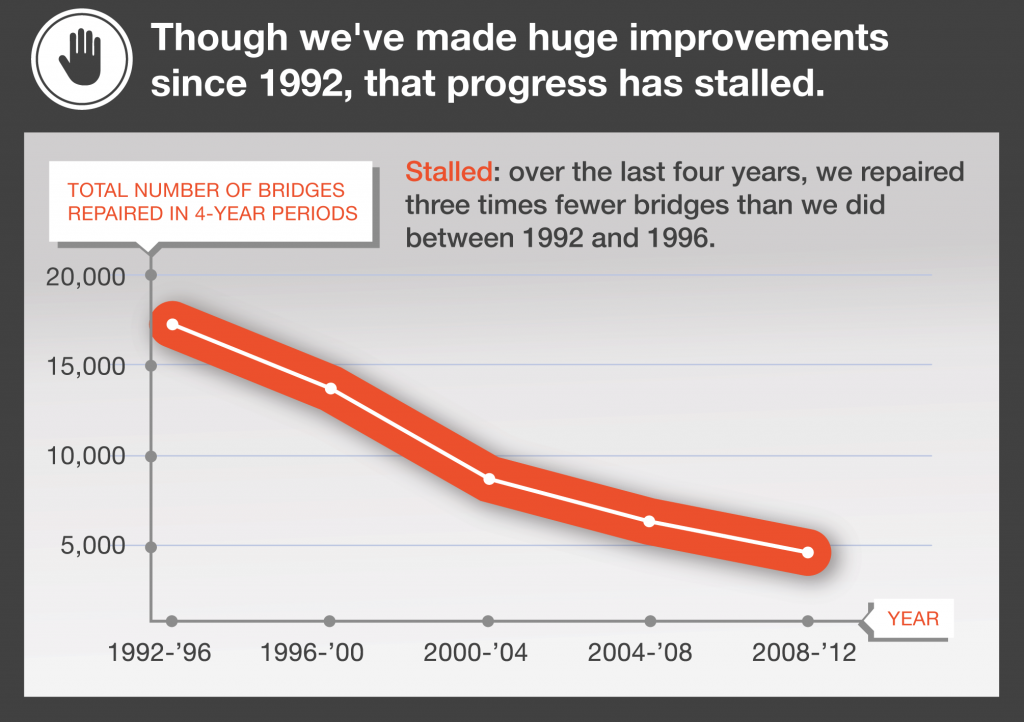

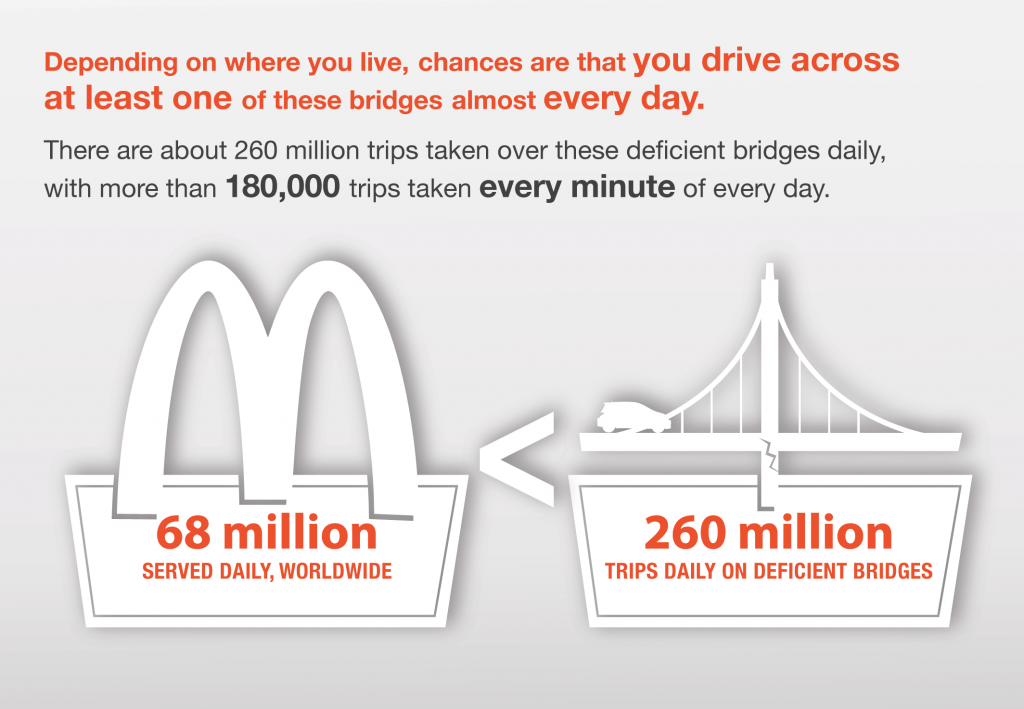

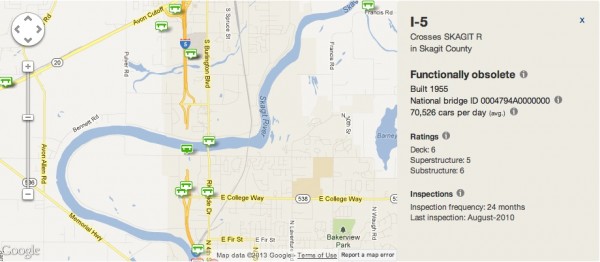

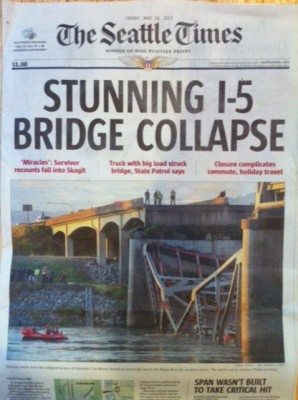

We should do a better job of repairing our aging bridges. As noted before, the Senate bill contains a new $500 million grant program to do exactly that. But which bridges? Senator Rob Portman from Ohio succeeded in having an amendment included that would ensure that the money can only to to repair bridges that are structurally deficient or functionally obsolete. That’s a done deal.

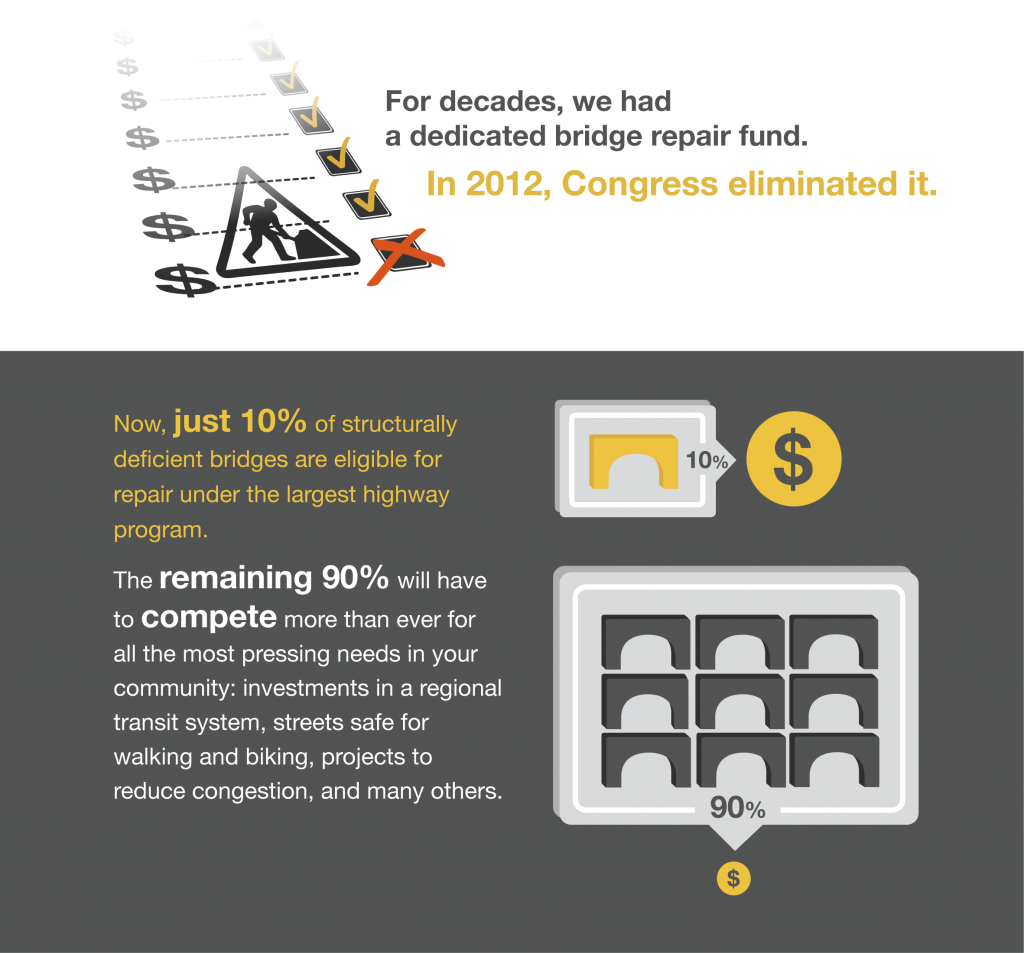

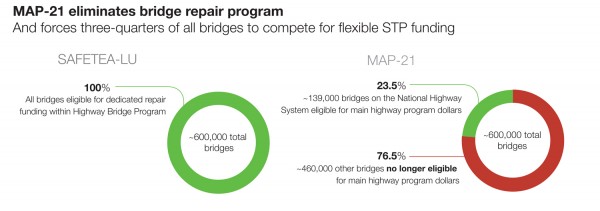

Lastly on bridges, Senator Cardin and Senator Gillibrand also proposed an amendment (No. 1760) requiring FHWA to report on highway and bridge conditions in each state as well as the amount of funding states are spending on highway and bridge repair — something that states once had to do before MAP-21 eliminated the dedicated bridge repair program. This would restore a requirement for states to closely track the conditions of their bridges and most importantly, how much they spend to repair these bridges compared to spending on new construction, helping taxpayers and citizens hold state leaders accountable for making progress.

There are some other amendments detailed below, which we’ll report on in the coming days.

It’s not too late to write or call your Senator and urge them to pass the Senate transportation funding bill when it comes before the full Senate. There were crucial swing votes on the committee that will be imperative to preserve when the full vote happens.

—

Other notable amendments we’re tracking:

- Flake 1764 (and Flake 1796) – Prohibits use of funds to subsidize cost of food service and first class service on Amtrak

- Flake 1765 (and Flake 1772) – Requires Amtrak to submit a report on losses in food service and first class service by route and line

- Flake 1766 – Eliminates the $15M in funding provided for the public transit emergency relief program

- Flake 1767 (w/ McCain) – Requires Secretary of Transportation to submit a report on programs carried out under chapter 2 of title 23 – which includes the Federal lands program and Transportation Alternatives

- Inhofe 1771 – Requires that at lease 20% of the funding in the “Bridges in Critical Corridors” program be used in rural areas

- Vitter 1775 – Requires the Secretary of Transportation to establish and publish selection criteria for TIGER including any required documentation. It also requires notification of awards within 3 days

- Vitter 1776 – Allows any project awarded funds under the “Bridges in Critical Corridors” program to proceed with a categorical exclusion from NEPA requirements

- Murphy 1783 (w/ Rockefeller and Blumenthal) – Requires that in any postings for Buy America waiver USDOT ‘assess the impact on domestic employment’ of the proposed waiver

- Coons 1788 – Increases funding for Amtrak from 1.452 billion to $1.565 billion

- Cochran 1794 (w/ Wicker) – Creates weight exemption for trucks on portions of Route 78 designated as an interstate after the effective date of the bill (this provision is similar to Wisconsin bill truck weight bill recently approved by the House)

.jpg)

With

With