Transportation emissions are on the rise

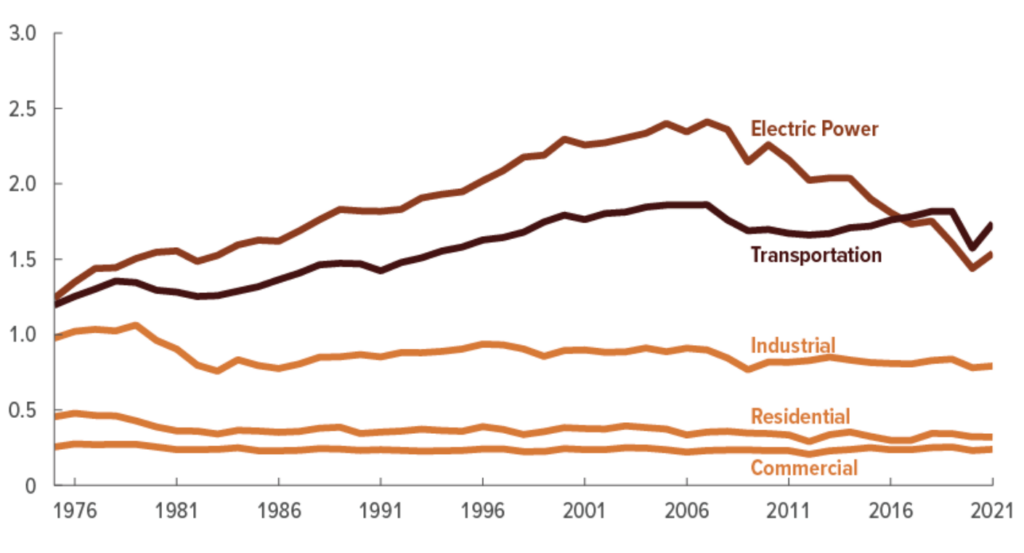

Tackling climate pollution emissions at scale requires major mitigation of emissions from transportation. The transportation sector accounts for the largest share of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the United States, contributing 31% of total GHG emissions in 2023. As the economy has rebounded after the COVID-19 pandemic, emissions across other major sectors are declining, while US transportation emissions are still rising, bucking the economy’s broader trend toward emissions reduction.

In recent decades, transportation emissions have continued to rise despite significant increases in light-duty vehicle fuel efficiency. This is a result of transportation and land use policies that push jobs and necessities further from where people live, necessitating longer and more frequent trips, made worse by the increasing proliferation of larger, inefficient vehicles.

From 1990 to 2022, there was a 19% increase in total transportation emissions from fossil fuel combustion, partially because of the 47% increase in total vehicle miles traveled (VMT) during that same period. In direct connection with this and over a similar period of time, lane miles grew faster than population, yet travel delays grew enormously.

As we discussed in our Driving Down Emissions report, these expensive and inefficient transportation and land-use policies encourage more and wider highways, lead to sprawling development, cause people to live farther away from the things they need and the places they go, and lead to longer trips and more driving merely to accomplish the same tasks. These policies are also bad for the climate and public health—polluting air and water, creating heat islands, and displacing green space and natural habitats. Inefficient transportation policies also increase transportation costs, a burden with inequitable racial disparities that also falls hardest on low-income households. Funding highway expansions, which prove time and time again to increase emissions, directly works against the strategies we are pursuing to mitigate transportation’s impact on the climate.

Electric vehicles alone won’t achieve our climate goals

The US Department of Transportation itself admits that we “will not be able to decarbonize the transportation sector without addressing increased demand.” It is undeniably necessary that we electrify vehicles but we are unlikely to reach our climate goals by only electrifying vehicles. Without reforming the same car-dependent land use patterns and sprawl-enabling transportation policy that fundamentally shaped the built environment in the 20th century (and today continues to drive up emissions), we risk undermining the climate goals of transportation electrification.

Electrifying the vehicle fleet is an undeniably massive part of strategies to reduce transportation emissions. However, the longer the transition to electric vehicles takes, the more important emissions reducing modes like walking, biking and transit are to meeting our goals. At the current pace, EVs alone are likely not enough to reduce emissions in time to stave off a 1.5-2 degree Celsius increase in average global temperatures. If not paired with reforms to reduce how much people need to drive and land-use reforms that make walking, biking, and public transit safer, more convenient, and more affordable options, the net climate and environmental benefits of the EV transition will be lost.

And while there are empirically strong climate benefits of EVs, at the end of the day, they do not solve key problems that car-dependence creates. Whether the fuel source is clean or carbon emitting, the further, faster, and more often people need to drive, the more energy from the grid or gasoline is required. The US vehicle fleet is in the midst of a trend toward increasingly larger vehicles, increasing vehicle weight. Larger vehicles put pedestrians and cyclists in greater danger during collisions and EVs are not immune to this larger automotive industry trend. Heavier vehicles, EV or gas-powered, take more energy to move their own weight and inflict more damage to roadways.

Finally, building modern vehicles entails the extraction and processing of rare materials shipped from across the world, often at great human and environmental costs. Smart usage of existing materials and minimizing travelers’ need for personal vehicles with high-quality public and active transportation options would help minimize pollution and the negative externalities of transportation decarbonization. Providing more options for walking, biking, and transit allows households to drive less or not at all, avoiding lifecycle emissions and financial costs to build, drive, and maintain a personal vehicle.

How the federal government funds transportation

The federal government distributes funding through two major grant types: formula and discretionary grants. Formula grants are distributed to states by the federal government via the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) and Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). Apportionments are allocated via a “formula” based on factors such as the share of federal highway lane miles, population, and vehicle miles traveled. Rules for apportionments are determined at the onset of each transportation bill, and funded by the Highway Trust Fund and general revenues.

Discretionary grants operate differently, with funds distributed at the discretion of the awarding agency. US Department of Transportation subagencies, such as the Federal Highway Administration, Federal Transit Administration, or the Office of the Secretary of Transportation, competitively select applicants from a pool of submissions, based first on criteria set by Congress and then on the priorities of the awarding administration.

Discretionary grant programs, which include the Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program and Charging and Fueling Infrastructure Grants, require recipients to know of and apply for funding, have their application evaluated, and then finally be selected before beginning the process to enter into a grant agreement and receive funds. This process can be burdensome for many communities, especially disadvantaged ones, and discretionary grant selection pools can be biased toward communities that already have the resources to know about opportunities that are open during limited time windows. Under the Biden administration, USDOT has made significant commitments to prop up technical assistance to enable more rural, tribal, and other disadvantaged communities chances to access funding opportunities. However, these priorities could be as easily abandoned as they were adopted under future administrations.

Congress determines the funding levels for grant programs, policies guiding the use of funds, and the scope of programs included in the federal transportation program. Typically, this happens on a five- to seven-year basis as appropriated funds for programs authorized by Congress lapse, with the process commonly referred to as “transportation reauthorization.” In the time between reauthorizations, policy from the previous bill is implemented but major changes to policy are historically reserved for the next reauthorization bill.

Since 1991’s Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA), there have been five transportation reauthorization bills including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, but the structure of the federal program has remained largely the same. States receive formula funding with broad eligibilities and few measures for accountability attached, plus the ability to transfer, or flex, up to 50% of funds across core formula programs. Since ISTEA, the number of programs has increased under some transportation bills and been consolidated under others, ebbing and flowing with each authorization.

How the 2021 infrastructure law charted the wrong course

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act(sometimes known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, but referred to as the IIJA in this report) was signed by President Biden on November 15th, 2021, including the reauthorization of the nation’s transportation program. This transportation reauthorization included historic levels of funding and created scores of new grant programs to address needs like climate resilience, safety, equity, and electrification. However, it continued a long-running bipartisan tradition of pouring more money into state-controlled formula programs that have produced disappointing results, such as a worsening national state of good repair, with little in the way of guardrails to ensure that funds are being used efficiently or effectively.

The IIJA is not the wholly unique, once-in-a-generation bill we were sold in terms of its approach to surface transportation program policy. It is instead a bigger version of the status quo of federal transportation policy, with many new, relatively small programs tacked on that are improperly sized to tackle the scale of current problems.

What would eventually become the IIJA started out as dueling proposals from the House and Senate, which were markedly different. The House’s superior INVEST Act proposed bold, bipartisan reforms to how the transportation program operates—prioritizing maintenance, safety, and access to jobs and services.

Crucially, the INVEST Act reformed the law’s largest programs (controlled by states and distributed by funding formulas) to ensure that states would be required to address their repair needs before building new assets, which are in truth fiscal liabilities because of their long-term repair costs. This single key provision would have drastically changed the landscape of how federal funding is used to build new emissions-increasing highway infrastructure.

In 2021, the American Society of Civil Engineers estimated that it would take $560 billion to repair existing roads and bridges—and adding new roads only increases how much we need to fix in the future. T4America estimated in 2019 that it would cost $231.4 billion annually over a six-year period to bring infrastructure into a state of good repair, but every new lane mile from expansion would add an additional $24,000 per year in costs.

This total cost will have only grown with inflation and the addition of new lane miles since then. With new research evaluating the true costs and benefits provided by our already extensive highway network now putting our existing investments in question, we must ensure the assets we commit to are providing the best value to the public.

However, text in the Senate’s version of transportation reauthorization eventually won out (due particularly to White House pressure to exclude the House and the House bill from the process) and the Senate’s text was used as the base for what became the IIJA in final negotiations.

The resulting differences were stark: Dedicated repair funding in the IIJA is limited, and states have the flexibility to spend would-be repair funding on building new roads or other priorities—without having to fix existing assets first. While the IIJA has provided immense funding overall for the transportation program, policies that could have led to a substantive transformation were left out, missing a massive opportunity to build out a modern, resilient, and multimodal transportation system. The IIJA dedicated more money to the same old system, and we got what Congress should have expected: even more of the same negative results.