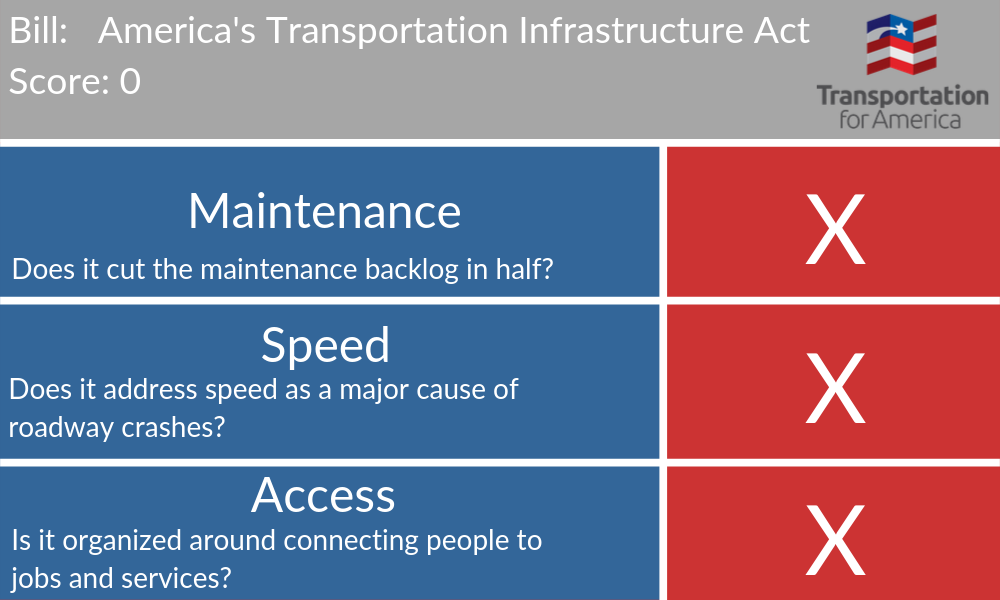

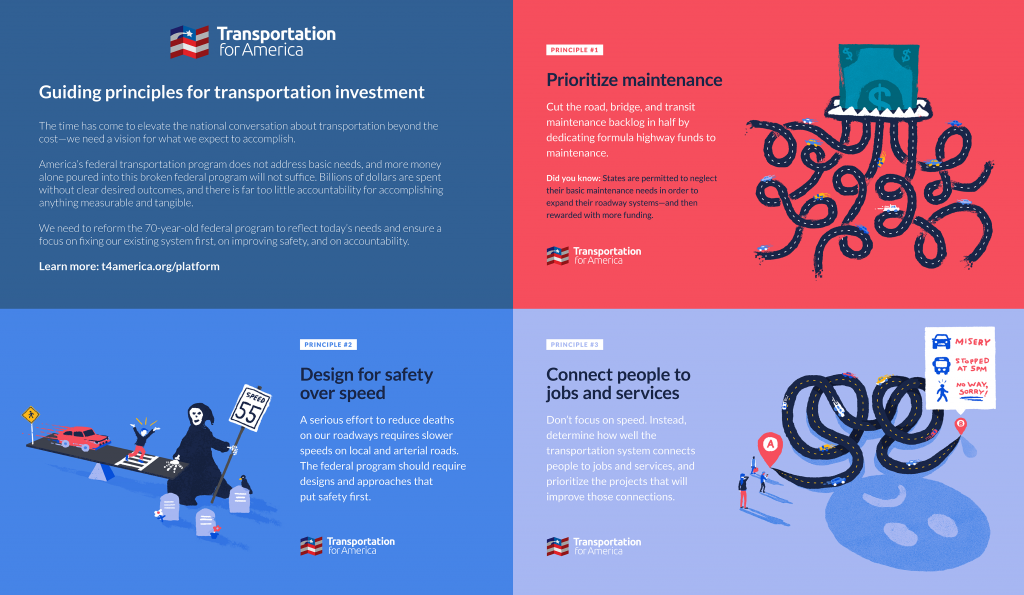

Last week was “maintenance week” at T4America, a week spent focusing on our first new principle for transportation investment to prioritize repair and commit to reducing the repair backlog by half. After a Twitter chat on Wednesday, on Thursday we joined a briefing on Capitol Hill for congressional staffers focused on the issue.

The new Future of Transportation Caucus chaired by Representatives Ayanna Pressley, Jesús “Chuy” García, and Mark Takano held a briefing on Capitol Hill yesterday to hear firsthand from three state transportation officials about the importance of shifting the federal transportation program to focus on maintenance first. Here are three quick things we learned.

It’s hard to get people to focus on maintenance—much less get excited about it

Although there was a strong turnout of staffers, there were far fewer than our recent briefing on climate and transportation, reminding us yet again that maintenance is never sexy and it’s hard to get people excited about it—much less make it a fundamental organizing principle of the federal transportation program.

Even if you do get people together to talk about maintenance, it’s a struggle to keep the spotlight on the issue. Even in this setting, ostensibly focused 100 percent on discussing the importance and mechanics of prioritizing maintenance, when the floor was opened up to questions, many immediately turned to funding. “Do you think that a vehicle miles traveled tax would be easier to implement than raising the gas tax?” one staffer asked.

Unfortunately, this was not the last question about money. T4America director Beth Osborne tried to remind everyone that this is precisely backwards from how we should be doing business with the federal transportation program.

“Federal transportation policy is unlike anything else because we start things off by talking about money, not what we’ll do with it. States don’t do this. No one wants to talk about outcomes. It’s time to tell voters what we’ll do with their money before we talk about needing more of it,” she said.

Absent useful data, politics will always determine spending, and politicians want to cut ribbons more than anything else

Ed Sniffen with the Hawaii DOT shared a story about how they transformed the agency to focus on maintenance and started a new asset management program, which is just a fancy way to say that they started tracking the conditions of their assets and using data to prioritize funding.

As they started this shift, Sniffen said that the long-time promised projects that had been on the books for years were some of the biggest obstacles to a new approach focused on preserving and stewarding the things they had spent billions over decades investing their state’s wealth into. “We didn’t have an asset management program, so those who complained the most got their roads fixed,” he said. “But we changed that so data controls everything. Costs and benefits now matter.”

Current Mississippi DOT Commissioner Dick Hall shared that when he was once on the legislative side years ago, he also had a hard time fully grasping why the state couldn’t afford to both radically expand and also prioritize maintenance. To this day, when it comes to grasping why maintenance needs to be the top priority, “for some reason I can’t seem to explain it to members of our legislature. But the members of the rotary club get it.” When he explains why the lion’s share of state transportation money is now going to repair, the public gets it. But the elected leaders still want their ribbon cuttings.

Better data and clear priorities can help ensure that funds are better spent.

States won’t do it on their own — the federal government needs to be the one to make repair a priority

The conventional wisdom about state DOTs is that they have two priorities when it comes to transportation funding. More funding, and limitless flexibility to spend it however they want. And that was largely the deal struck by Congress with the influential state DOT lobbyists in MAP-21 in 2012 and the FAST Act in 2015: in exchange for a weak system of performance measures, states got even more flexibility for spending slightly more money however they wish.

So it was striking to hear state transportation officials practically begging the staffers in the room to make maintenance and repair a concrete, binding federal priority. When asked about the difficulty of selling a maintenance-first approach to elected leaders in his state, Commissioner Hall explained how internal political pressure so often leads to states spending money they urgently need for repair on new capacity projects. They’ve finally made some progress in Mississippi on making repair their number one priority, but he had a crystal-clear answer for the attendees at the briefing:

“If you want us to prioritize maintenance, then you’re going to have to tell us ‘you gotta do it!'”

The question remains: will Congress heed this request and render this debate moot in state transportation agencies across the country? Or will they allow states to continue buying things they can’t afford to maintain and then just return to Congress and beg for more money down the road?

That choice is in Congress’ hands.

Stay tuned next week for our “safety over speed” week, starting on Monday, November 4th. We’ll be diving deep into our second principle on why safety has to be the overriding consideration when it comes to street and road design.