New nationwide survey shows that prioritizing road repair, improving transit, and reducing driving are more popular options for spending transportation dollars

WASHINGTON, D.C. (June 29) — A new nationwide survey of American voters’ attitudes reveals a significant divide between voters’ attitudes about the best short-and long-term solutions for reducing traffic, versus the actual priorities of their state and local transportation agencies.

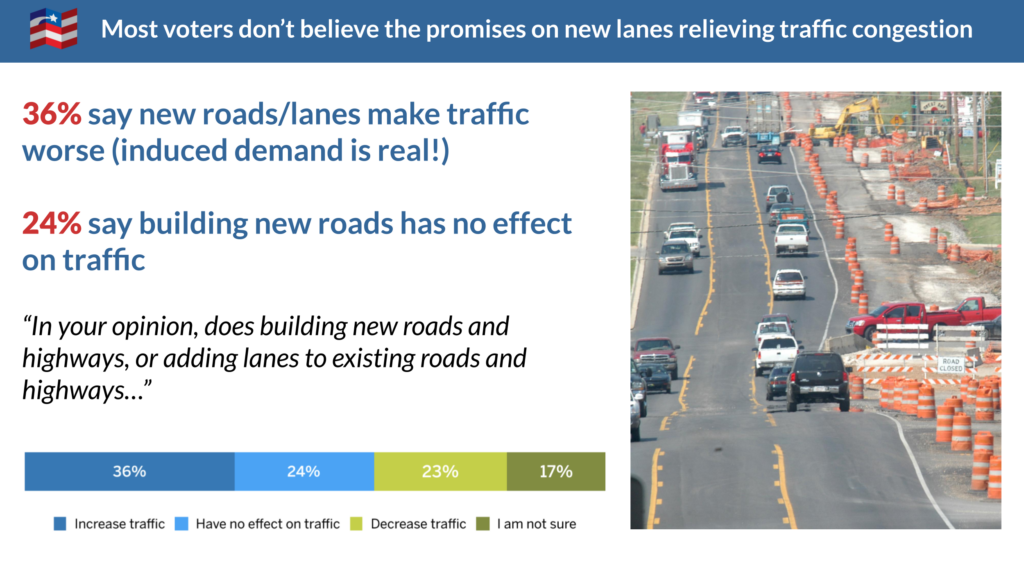

In 2021 The Washington Post estimated that highway widening and expansion consumed more than a third of states’ capital spending on roads (over $19 billion). These projects were backed by promises to reduce congestion. The public isn’t buying it. The results of a national survey of 2,001 registered U.S. voters—90 percent of whom own a car they drive regularly—underscores a widely shared belief that highway expansion doesn’t work as a short- or long-term strategy for reducing traffic and that we should invest more in other options.

- 70 percent of respondents agree that “providing people with more transportation options is better for our health, safety, and economy than building more highways.”

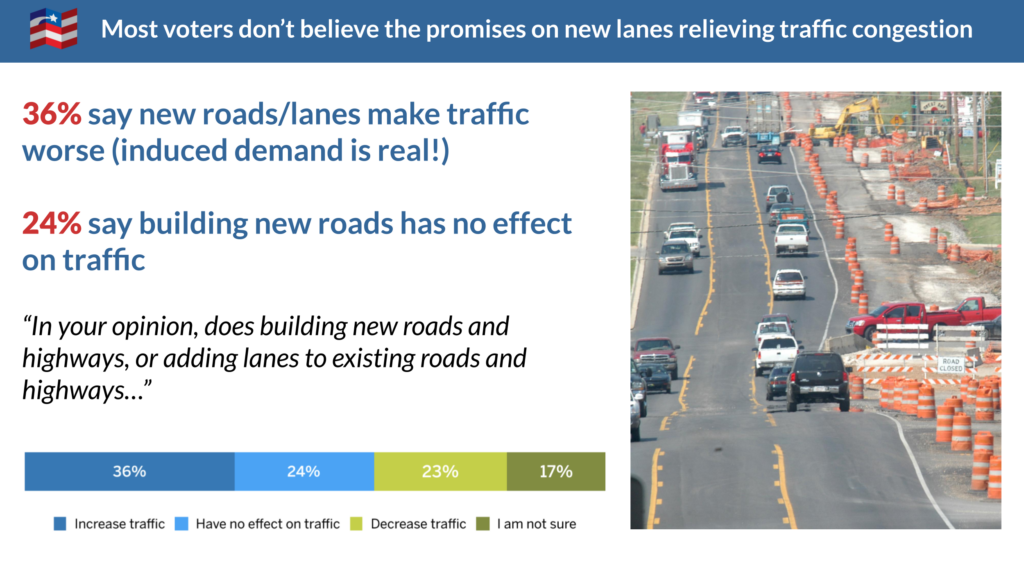

- 67 percent of respondents agreed that “expanding highways takes years, causes delays, and costs billions of dollars.” The same percentage believes that “widening highways attracts more people to drive, which creates more traffic in the long run.” Only 11 percent felt state DOTs actually deliver congestion relief with highway expansions. In other words, the public understands the concept of “induced demand,” which is widely ignored by state legislatures, DOTs, Congress, and federal agencies.

- 69 percent of respondents agree that “it’s more important to protect our quality of life than to spend billions of tax dollars on expanding highways. By removing a few miles of highway and adding more transportation options, like trains, buses, bike lanes, and sidewalks, we can have healthier communities.”

- 71 percent of respondents agree that “no matter where you live, you should have the freedom to easily get where you need to go. Almost all government spending on transportation goes to highways. Instead, states should fund more options, like trains, buses, bike lanes, and sidewalks.”

The survey revealed a deep dissatisfaction with the overall status quo of state and local transportation spending which overwhelmingly prioritizes spending on new roads, often at the expense of keeping roads and bridges in good condition, investing in transit and safe streets for walking or biking, or reducing the need to drive overall. Given seven choices for the best short- and long-term solutions for reducing traffic, the least popular option was “building new freeways and highways,” even as states are poised to spend tens of billions on new highways thanks to the 2021 federal infrastructure law.

“Our country remains on a highway spending spree while requests for basic investments in walkability and transit are given low priority. I hope this survey serves as a wake-up call to politicians that the public is clamoring for reasonable investments in our health, climate and quality of life, not traffic-inducing polluting highways,” said Mike McGinn, Executive Director of America Walks.

Prioritizing the repair of existing roads and bridges first was the top option for how states should be investing their transportation funding (selected by 22 percent of respondents), though Congress has long agreed—in a strong bipartisan fashion—not to institute any binding requirements to prioritize repair first.

“We’re repeatedly told by leaders on Capitol Hill that requiring states to prioritize maintenance first is just too controversial,” said Beth Osborne, director of Transportation for America. “But this survey shows yet again that there’s no controversy among the people they serve—they’re beyond ready to retire the last generation’s playbook when it comes to improving mobility and getting them where they need to go.”

While “reducing congestion” is the top policy goal that shapes the spending decisions of most state DOTs, traffic is not a huge stumbling block for most people to access what they need. Just one in four said they find it difficult to get around.

Survey respondents expressed positive feelings about a range of messages about spending transportation money differently, demonstrating that voters are looking for new ideas, policies, and/or investments that address their problems and deliver meaningful benefits to people and communities—instead of just doing the same old things over and over again. (See attached PDF for full results on pages 19-22, all of which were supported by over 60 percent of respondents.)

“These results are clear: Americans are eager to see the transportation investments that can connect and repair their communities,” said Rabi Abonour, a transportation advocate at NRDC (Natural Resources Defense Council). “Federal, state and local leaders should follow the lead of the public and invest in the public transit and related projects that will really improve mobility, clean the air, and address climate pollution.”

About the poll

Hattaway Communications, a strategic communications firm based in Washington D.C., was retained to conduct this survey of 2,001 registered voters and assess their awareness of relevant issues, attitudes toward transportation projects, and aspirations for their communities. The survey was fielded online, between February 23–March 7, 2023, and reflects the demographic and geographic composition of the United States.

This survey was supported by the Natural Resources Defense Council and a grant from the Summit Foundation.

###

Transportation for America is an advocacy organization made up of local, regional, and state leaders who envision a transportation system that safely, affordably, and conveniently connects people of all means and ability to jobs, services, and opportunity through multiple modes of travel. T4America is a program of Smart Growth America. Learn more at t4america.org

America Walks is leading the way in advancing walkable, equitable, connected, and accessible places in every community across the U.S. We are the national voice for public spaces that allow people to safely walk and move. At the regional, state, and neighborhood levels, America Walks provides critical strategic support, training, and technical assistance to partner organizations and individuals to effectively advocate for change. https://americawalks.org/

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) works to safeguard the earth—its people, its plants and animals, and the natural systems on which all life depends. https://www.nrdc.org/about