Building from conversations with business, civic and elected leaders in communities throughout the country, Transportation for America has developed a platform of seven broad policies to reboot the nation’s federal transportation program and put it, and the nation, on a sound footing.

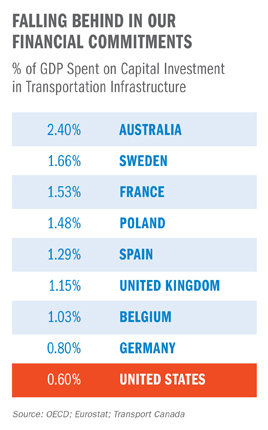

The nation’s trust fund for transportation is teetering on the brink of insolvency, potentially bringing scores of projects planned for the next fiscal year to a grinding halt. Lawmakers in Congress need to pass a new federal transportation bill before it expires in September.

Even more needs to be done. While MAP-21 made important changes to the federal transportation program, the program still needs a reboot in the update due this fall.

Our cities, towns and suburbs across the country — the local centers of commerce that form the backbone of America’s economy—are also facing serious challenges: They know they must have top-notch transportation networks to attract talent, compete on a global scale and preserve their quality of life. They know they need to get workers of all wage levels to their jobs. They also know they need to eliminate crippling bottlenecks in freight delivery. These communities are stretching themselves to raise their own funds and to innovate, but without a strong federal partner the twin demands of maintaining their existing infrastructure and preparing for the future are beyond their means.

These challenges, as difficult as they are, present an opportunity to re-evaluate—and reinvigorate— the federal transportation program in ways that will boost today’s economy and ensure future prosperity.

The local leaders we’ve been speaking with have made it clear that if Congress wants support for raising more revenue for transportation, they need to give these folks at the local level more reasons to believe that it will be to their benefit.

Q: So how do we improve their confidence that more money for transportation will flow down to the level where it’s needed the most?

A: By adopting policies to refocus the federal transportation program on innovative, locally driven transportation solutions. For example, the second group of policies from our platform:

Here’s what T4America’s Beth Osborne had to say about using competition and incentives to direct more money down to the local level while also generating better projects in the Atlantic Cities just this week:

At the moment, though, these centers of our economy have access to only a fraction of the money they pay into the nation’s transportation program. What would they do with the money if they had access to more of it? We have had a chance to see over the last five years with the TIGER program, which I helped oversee during my time at U.S. DOT. …Many excellent projects made the cut, and made a big difference. …All solved multiple problems at once, and almost none would have been funded under existing silos. The big lesson: Competition spurs innovation that formula funds never ever will. Competition generates incredible excitement and a desire to outdo your neighbor. As a result, federal dollars are made to go farther, more non-federal funds are brought in from both public and private sources, and every penny is targeted to accomplish multiple goals.

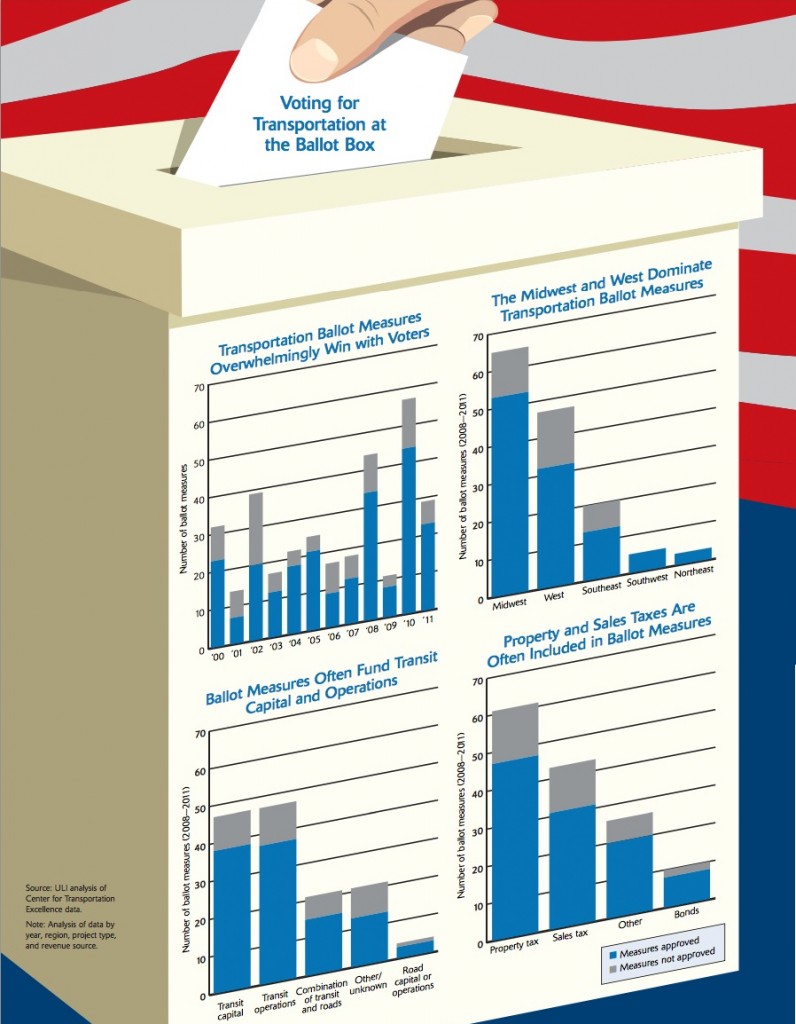

Visit t4america.org/policies to view the rest of the full platform and learn more about the proposals reflecting the needs expressed by local leaders across the country. They are reaching for economic opportunity with forward-looking plans, and going to voters to raise revenue, but they lack the access to enough resources to build the necessary 21st century infrastructure. Our communities need a dependable federal partner.

Incorporating their proposals into MAP-21′s replacement will help their cities, towns and suburbs prosper and flourish as places where businesses can thrive and people of all incomes and ages can live healthy and productive lives.

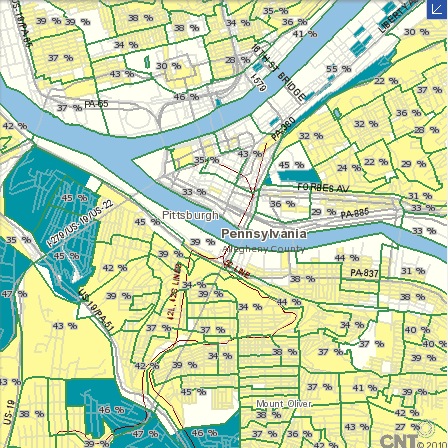

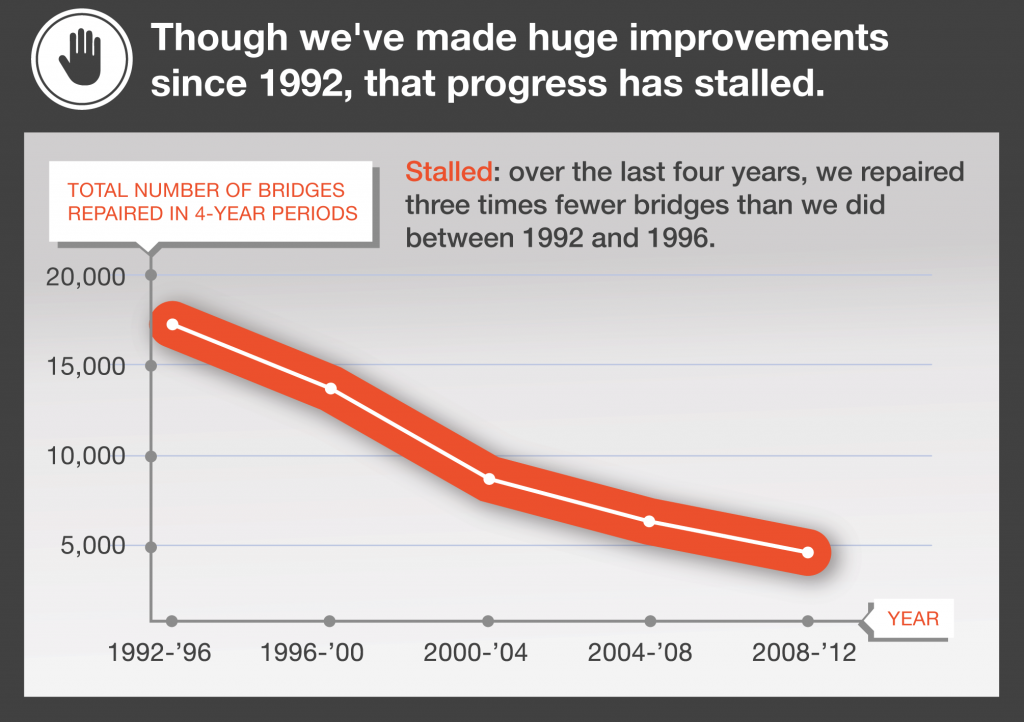

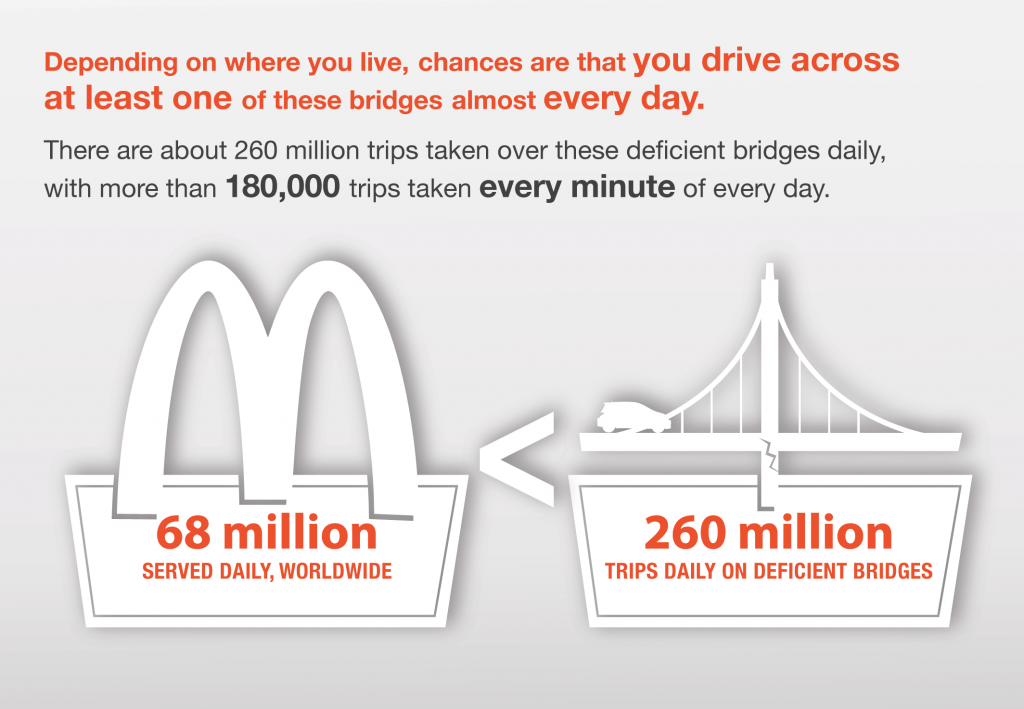

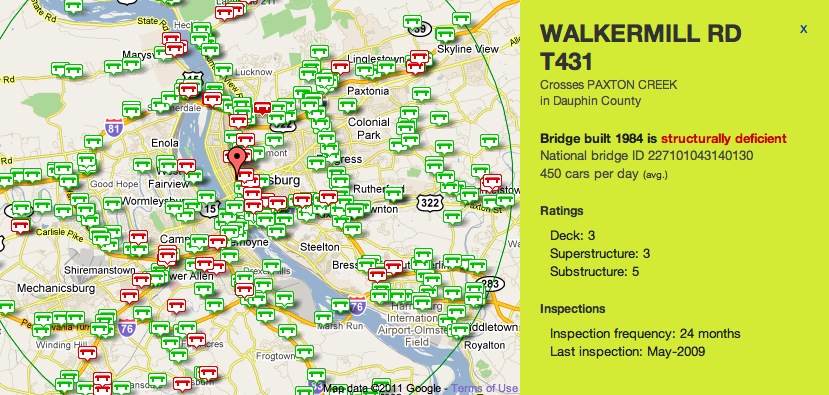

A report being released Wednesday by T4 America chronicles the state of our nation’s bridges, with accompanying data and reports for all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Our country is facing a backlog of deficient bridges that need repairs and maintenance to stay open and safe, with needs far greater than what we’re currently spending.

A report being released Wednesday by T4 America chronicles the state of our nation’s bridges, with accompanying data and reports for all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Our country is facing a backlog of deficient bridges that need repairs and maintenance to stay open and safe, with needs far greater than what we’re currently spending.