When Maryland’s Intercounty Connector (ICC) highway opened in 2011, it did more than create a new east-west toll road between I-270 and I-95 in the northern suburbs of Washington, DC: It also severely hampered Maryland’s ability to build other large-scale transportation projects for years to come. But now there’s significant momentum to raise new state revenues for transportation to ensure that the state won’t have to shelve their plans for a 21st century transportation system.

Update 4/3/12: The Senate passed the House bill (HB515) last Friday, heading to Gov. O’Malley for his signature. The separate “lockbox” bill will require a conference to reconcile the differences in House and Senate versions.

With MAP-21 out the door, attention has shifted from Washington to the states. In many cases, states are deciding that they need more money for transportation and are embarking on ambitious and often groundbreaking plans to raise additional revenues for transportation. This post is part of a longer series we’ll be doing in 2013 examining how states are addressing the need for more transportation dollars, along with key policy changes. Visit the home for state plans here, where we’re tracking all of the news. – Ed.

While half of the ICC’s almost $2.6 billion cost was paid for with future tolls that don’t really impact the state’s transportation budget year to year, the other half ($1.3 billion) was covered by sources that have huge impacts on Maryland’s ability to build any other significant large transit or road projects.

The state spent $265 million in general funds and though the $180 million from the state’s Transportation Trust Fund represents only about 10 percent of what the state gas tax and vehicle fees bring in each year, Maryland is also devoting $750 million in future federal funds they haven’t yet received to the project — or almost 130 percent of what the state receives from the feds each year for all of their state highway needs. ($580 million in FY12.)

That means that a large share of Maryland’s future federal transportation dollars under MAP-21 — which itself represents a loss in real dollars over previous transportation bills — are already spoken for by this mammoth project.

The ICC under construction in 2011, Creative Commons Flickr photo by Dougtone.

Even without building the ICC, like a lot of states, Maryland would certainly have to make some tough decisions. But with it, it’s easy to understand how state and independent analysts have been saying that by 2018, Maryland will only have enough money to cover maintenance and repair, making it nearly impossible to fund any new highway projects or any of the long-awaited and much needed public transportation projects, including the new Red Line subway in Baltimore, the Purple Line rail link for Metro and the innovative Corridor Cities Transitway rapid bus line in the DC region.

Get Maryland Moving, a new coalition of advocates of all stripes from across the state, coalesced around the urgent need to keep these worthy projects (and many others) from being relegated to a perpetual “wouldn’t that be nice” wish list, providing Marylanders with other options for getting around, and ensuring that Maryland doesn’t have to cease all investment in their transportation network.

Since the (state) gas tax was set at its current level of 23.5¢ in 1992, construction costs have doubled, according to this report from the CA DOT. Simply put, just like the federal gas tax that was last increased in 1993, inflation has far outpaced the value of the gas tax, and with Americans driving fewer and fewer miles each year in more fuel efficient vehicles, they each bring in less revenue.

A rally in Annapolis at the State House organized by Get Maryland Moving in March 2013.

Urged along by the diverse Get Maryland Moving coalition, the current proposal started from a plan put forward by Governor Martin O’Malley, the President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House, though it has been modified as it has moved through the state legislature. The House passed the bill (HB1515) just last week, and the Senate is due to debate and vote on it soon.

You can view the Governor’s initial plan on our page of state transportation funding plans, but here is the deal as it currently stands in the Maryland legislature. The plan would:

- Index the gas tax to inflation starting immediately (with a ceiling of 5 cents maximum increase in any given year.)

- Add a three percent sales tax at the gasoline pump, phasing that in over a period of three years starting this summer.

- There are other provisions that could change the sales tax rate on gasoline that have to do with internet sales tax. In short, if Congress allows states to tax internet sales, Maryland will devote that revenue to transportation. If not, they’ll raise the sales tax on gas to five percent.-=

- Raise $4.4 billion for transportation over six years (including the ability to borrow against increased future revenues.)

A popular argument against the tax has been the supposed increase that residents will see at the pump — 13-20 cents per gallon as reported by state analysts and trumpeted loudly above the fold by the Washington Post and other outlets. But gas prices fluctuate wildly even within submarkets — many places may see gas prices go up by 20 cents a gallon in just a few weeks at certain times of year.

Along those lines, the Get Maryland Moving coalition visited a bunch of Maryland gas stations on one particular day to show the wild variety in prices, sometimes at locations within sight of one another, and produced this terrific graphic.

The Get Maryland Moving coalition consists of some of T4 America’s core local partners in the region as well as strong representation from local elected officials and business groups that don’t want to see Maryland drop the ball on projects like the Purple Line that would create a vital (and decades overdue, many would argue) east-west transit connection in the region that would also eliminate long rides through the core of the Metro system to reach the opposite end of the Red line.

Most of the leaders of the suburban counties in the DC metro region have been strong advocates for the plan in the legislature. From The Washington Post:

“This is a big problem, and we need a big solution,” Montgomery County Executive Isiah Leggett (D) testified at a hearing of the Senate Budget and Taxation Committee. “My view is go big or go home.”

Leggett appeared on the same panel with Prince George’s County Executive Rushern L. Baker III (D) and Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake (D). All three praised a bill introduced by Senate President Thomas V. Mike Miller Jr. (D-Calvert) but said they remain open to alternative methods to raise more money for transportation.

The moment of truth is coming soon for Maryland’s transportation future. The 90-day legislative session ends in just a few weeks in early April.

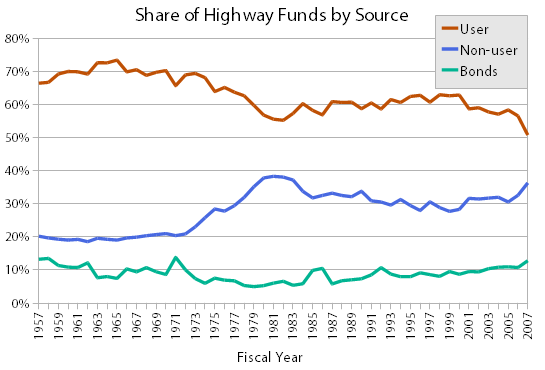

Critics of public transportation often cling to the canard that government should not subsidize a transportation option that cannot pay for itself. These naysayers reference “self-sustaining” roads and highways, which receive funding from user-fees – in this case, the federal gas tax.

Critics of public transportation often cling to the canard that government should not subsidize a transportation option that cannot pay for itself. These naysayers reference “self-sustaining” roads and highways, which receive funding from user-fees – in this case, the federal gas tax.

A recent California Supreme Court decision could restore billions in funding for public transportation in the nation’s most populous state.

A recent California Supreme Court decision could restore billions in funding for public transportation in the nation’s most populous state.