Yesterday the Senate passed the bipartisan infrastructure deal, which incorporates the Senate transportation reauthorization in all its good and all its flaws. We outline what’s in it and where to go from here.

Mostly lip service for climate and equity

The bipartisan infrastructure deal includes a lot of new spending, but that spending isn’t directed toward outcomes, much less the priorities that the President articulated in The American Jobs Plan. Though this bill mentions safety, climate, and equity often, as it stands, it will fail to produce meaningful shifts. “The White House will soon discover that they’ve dealt themselves a challenging hand in their long-term effort to address climate change and persistent inequities, while kicking the can down a crumbling road that’s likely to stay that way,” T4America director Beth Osborne said in our full statement after Tuesday’s final vote.

Overall, despite all the headlines about the $1.2 trillion total investment, the bulk of the bill’s five-year funding for transportation will be governed by the two reauthorization proposals approved by Senate committees earlier this year and folded into this deal. (Here’s some of what we had to say about the highway title, and the Commerce committee’s rail and safety title. A transit title was never produced by the Banking committee.)

Some funds ($1 billion) will go to reconnecting communities separated by highways, an important step in undoing the ongoing damage of urban renewal programs. However, these funds are a fraction of the $20 billion originally proposed by the House and are dwarfed by historic increases in highway spending, without any guarantee that future highway expansions won’t separate more communities. (This isn’t just some historic, old problem from the Civil Rights era—it continues today. See I-45 in Houston, I-49 in Shreveport, I-5 in Portland, etc.)

There’s language supporting Complete Streets and vulnerable transit users, but the overall status quo approach to safety will undermine those modest improvements. States are still allowed to shift safety funds for non-safety projects and set annual “safety” targets for increasing numbers of people to die on their roads, with no penalties or accountability for doing so. Competitive funding is offered for states, regions, and local governments, but local leaders still have very little control over the projects and the designs of projects that will be built in their neighborhoods with formula funds.

This bill includes a climate program that many states can opt out of, so long as their population and economy is growing faster than their carbon emissions. It offers funding for electric refueling stations, but a late change diverted one-third of those funds to emissions-producing natural gas and propane stations. And the freight program is still written to have states identify their biggest freight needs and then require the majority of the available freight funding to only address the highway projects on that list.

There were four amendments that could have significantly improved the bill’s repair, climate, and equity outcomes (listed below). Along with nearly all of the 400 amendments offered, none of these four were even considered.

- Sen. Kaine (VA) offered a proposal to require a “fix it first” approach to highway funding

- Sen. Klobuchar (MN) offered a proposal to eliminate regressive safety performance targets

- Sen. Cardin (MD) offered a proposal to create a greenhouse gas performance measure

- Sen. Warnock (GA) (and Sen. Cardin (MD)) offered a proposal to increase funding for the Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program to $5 billion

Rail is the deal’s silver lining

The Senate Commerce Committee’s plans for rail, which we praised in June, made it into the final deal, increasing funding for passenger rail across the board. Amtrak is rightfully treated as a valuable national service deserving of federal funding. The mission of Amtrak is to now maximize convenience and service to the customer, not to cut costs making the experience difficult to those traveling on rail. Plans to duplicate the success of the Southern Rail Commission across the country also made it into the final deal.

This bill doesn’t meet the moment

The only major cut made to the original bipartisan deal announced with fanfare in June was to transit, by $10 billion.

The deal’s $39 billion is still more than what the current FAST Act has been providing over the last five years, and the White House believes that the overall increase is a win. But Transportation for America cares far more about how the money is spent. This bill provides every category of spending with more funding, but it doesn’t change the balance nor does it create accountability to the taxpayer for results.

The administration believes they can run any program so well that the flaws don’t matter. This is an admirable goal, but one that’s putting them in a bind. There are a record number of competitive grant programs, which provides great opportunity for this USDOT (and future ones) to implement their priorities, but they’ll have to battle the flaws in their own legislation. We are not sure that an administration that struggled to do things like call for state road safety targets that would improve safety, or stand on their laurels to make long overdue safety updates to the manual that guides street design is really up to the challenge of, for example, stopping every project that harms a minority neighborhood. We certainly hope they are and will do all we can to help. But the administration has put themselves in a challenging position.

The IPCC’s latest climate report calls for transformative, immediate change—less emissions, less waste. This bill is far from transformative. It adds some new money for programs to fix some problems while spending far more perpetuating those same problems.

Going forward

Now that the reconciliation bill has passed in the Senate, the House is expected to come back during the week of August 23rd, before the end of August recess, to consider the infrastructure deal and the reconciliation package. Though it’s not clear yet if we can expect to see further policy changes to the infrastructure bill, it will be worthwhile to remain engaged in how additional funds will be distributed through the budget reconciliation process in the House. The budget resolution passed in the Senate gives the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure $60 billion in additional budget authority to appropriate how they see fit.

Beyond that, our eyes turn to the administration to see how they’ll manage this program. They’ll have control over a lot of money, and they’ll need to move quickly to provide better accountability for lowering emissions, improving racial equity, and increasing access to economic opportunity. They’ll have the power to provide greater control for local governments over what is built in their communities. We’ve been keeping tabs on what the administration has accomplished so far, and we’ll continue to do so from here on out. If they’re going to accomplish what they set out to do, they’ll need help from all of us to do it.

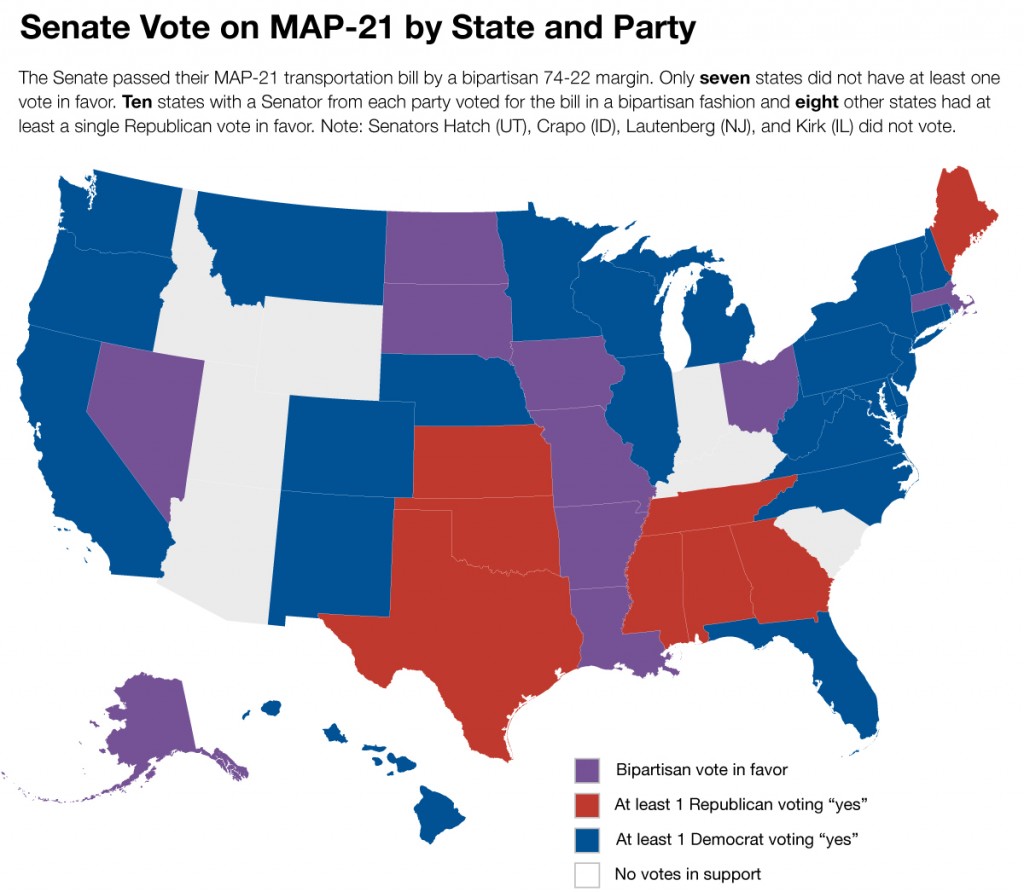

It’s time for Democrats and Republicans—and more of the press—to think about what a transportation program can and should achieve: access to jobs for rich and poor, a safe travel environment for those in and out of a car, and a well-maintained system. None of these goals are partisan. Democrats and Republicans may come to each priority for slightly different reasons, but there is a new bipartisanship that can emerge around creating a better transportation system if we just look at what we are building and not just how much we can build.

It’s time for Democrats and Republicans—and more of the press—to think about what a transportation program can and should achieve: access to jobs for rich and poor, a safe travel environment for those in and out of a car, and a well-maintained system. None of these goals are partisan. Democrats and Republicans may come to each priority for slightly different reasons, but there is a new bipartisanship that can emerge around creating a better transportation system if we just look at what we are building and not just how much we can build.