With a new Congress preparing to take office—bringing hopes of an infrastructure stimulus with them—it’s time to end an outdated agreement keeping American transportation stuck in the ‘80s: restricting public transit to only 20 percent of federal transportation funding while highways get 80 percent. Sign our petition today to tell Congress to fund them equally.

Can you imagine what we could accomplish if transit was funded as much as highways? Photo of Metroway (bus rapid transit in Northern Virginia) by BeyondDC on Flickr’s Creative Commons.

It’s critical that Congress funds public transit and highways in the next transportation authorization, ending an outdated rule that makes it near impossible for states and local governments to deliver the high-quality public transportation Americans want. Sign our petition to urge Congress to fund transit as much as highways.

Since 1982, thanks to an agreement signed by President Reagan, spending from the federal Highway Trust Fund has followed this formula: 80 percent for highways, 20 percent for public transportation (though in reality, transit gets much less). The logic behind this was that since the Trust Fund’s funding came from the gas tax drivers pay at the pump, most of the funding should be spent on highways.

As our colleague Emily Mangan wrote this summer, this logic no longer applies because the Highway Trust Fund hasn’t been a trust fund by any definition of that term in a long time. It hasn’t been exclusively funded by the gas tax since 2008, when it ran out of money because the gas tax was no longer sufficient to cover expenditures. To stay afloat, the trust fund received huge infusions of general taxpayer dollars totaling over $144 billion—meaning that every taxpayer is funding transportation, whether they bought a single gallon of gas or drove a mile this year or not.

Yet we still applied this arbitrary funding split to the influx of new transportation funds in the Recovery Act of 2009, which was sourced entirely from deficit spending from the general fund and not a single dime from gas tax user fees. Yet roughly 75 percent of the Recovery Act dollars went to roads.

The consequences of not funding transit and highways equally

Even though highways receive the overwhelming majority of federal transportation funding, they fail to solve our transportation problems on their own. In fact, this huge amount of highway funding makes our problems—congestion, carbon emissions, dangerous roadways, reduced access to jobs and services—worse. Because there’s no rule requiring that states spend highway funding on maintenance before expansion, or any performance measures requiring that states improve people’s access to jobs and services by all modes, our highway investments wind up just increasing congestion and carbon emissions while disconnecting Americans from the daily services they need.

Guaranteeing that highways receive 80 percent of federal funding also reduces states’ and local governments’ freedom to choose for themselves what they want to build and how they want to solve their own transportation challenges. According to recent polling, voters overwhelmingly believe that their communities and the country as a whole would benefit from increased transit investment. But Congress has hampered states’ and communities’ ability to deliver this for decades by putting their thumb on the scale and incentivizing highway expansion with huge amounts of funding, making it incredibly difficult to choose a transit solution to a transportation problem.

This 80/20 split also leaves the transit infrastructure that already exists out to rot. According to the American Public Transportation Association, addressing the backlog of deferred transit maintenance backlog would cost $90 billion—or just two years of highway funding.

It doesn’t have to be this way. If Congress were to end the arbitrary 80/20 split and fund transit and highways equally, we could fix our aging public transportation infrastructure and provide the frequent and reliable service necessary to connect people to jobs and services. With more transit funding, states would be incentivized to make roadway investments that accommodate transit, not compete with it, such as investments in complete streets and land-use changes that make it safe and easy to bike and walk and therefore to access transit.

Meaningful and consistent investment in public transportation is critical to reducing our carbon emissions, improving public health, dismantling barriers to opportunity—especially those faced by people of color—and supporting our economic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. It’s time for Congress to free states and local governments from this arbitrary 80-20 split in transportation funding and let them invest in transit.

Congressional leadership and junior members offer hope

There are numerous elected officials in Congress who understand the power of transportation policy to strengthen our economy, save lives, dismantle barriers to opportunity, and reduce our greenhouse gas emissions. From the innovative Future of Transportation Caucus, to leaders like Rep. Peter DeFazio, and to bipartisan members of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, the incoming Congress has a real shot at reforming transportation policy to work for all Americans—regardless of if they drive or not.

The House of Representatives has a great jumping off point with the INVEST Act, a bill they passed this summer, that starts to finally connect transportation funding to the outcomes Americans want. Instead of pumping more general funds into the existing program, the bill employs performance measures and requirements to align funds with our goals: reducing our enormous backlog of roadway maintenance, decreasing congestion and carbon emissions, and making our streets safe for all road users. We strongly urge the incoming House of Representatives to pick up this bill again—and fund transit and highways equally this time.

To kick off that effort, next month Rep. Jesús “Chuy” García (a founding co-chair of the Future of Transportation Caucus) will introduce a resolution to the House of Representatives urging members to support funding transit and highways equally in the next surface transportation authorization. A resolution like this would have been unthinkable just three years ago—a real testament to the changing attitudes towards transportation policy.

Tell Congress: it’s time to end the 80-20 split

With federal transportation policy up for reauthorization this year and hopes for an infrastructure stimulus hitting the floors of Congress running high, now is the time for our elected leaders to solve our transportation problems and fund transit and highways equally. Sign our petition to urge Congress to end the 80/20 split and fund transit and highways equally.

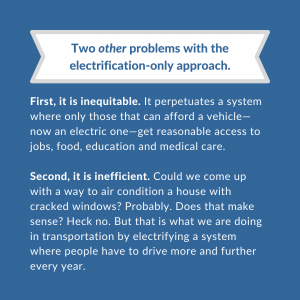

We won’t be able to increase fuel efficiency and electrify cars faster than VMT is rising, reducing the impact of electrification particularly in the next 10-20 years. And VMT is rising because the current federal transportation program—the broken program that the Senate is proposing to effectively renew with more money for five years—

We won’t be able to increase fuel efficiency and electrify cars faster than VMT is rising, reducing the impact of electrification particularly in the next 10-20 years. And VMT is rising because the current federal transportation program—the broken program that the Senate is proposing to effectively renew with more money for five years—

It’s time for Democrats and Republicans—and more of the press—to think about what a transportation program can and should achieve: access to jobs for rich and poor, a safe travel environment for those in and out of a car, and a well-maintained system. None of these goals are partisan. Democrats and Republicans may come to each priority for slightly different reasons, but there is a new bipartisanship that can emerge around creating a better transportation system if we just look at what we are building and not just how much we can build.

It’s time for Democrats and Republicans—and more of the press—to think about what a transportation program can and should achieve: access to jobs for rich and poor, a safe travel environment for those in and out of a car, and a well-maintained system. None of these goals are partisan. Democrats and Republicans may come to each priority for slightly different reasons, but there is a new bipartisanship that can emerge around creating a better transportation system if we just look at what we are building and not just how much we can build.