When ridership plummeted at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, transit agencies across the country experienced substantial operating budget deficits. The federal government responded by rolling out multiple relief packages to help agencies make it through the worst of the pandemic. Now, in early 2023, funds are running out. We surveyed transit agencies nationwide to see where they stand as federal support dwindles.

What is the transit fiscal cliff?

According to the American Public Transportation Association, in the five years leading up to the pandemic, ridership was slowly declining across a range of transit agencies. Even with relatively stable ridership, transit agencies were already struggling to make ends meet.

When the Covid-19 pandemic caused national lockdowns, ridership plummeted, causing revenues from fare collection to drop to almost zero. Without fare revenues, transit agencies no longer had the funding to cover their operating costs. And the federal government stepped in, rolling out three separate emergency relief packages, and incorporating increased support for transit agencies in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). (Learn more about what the IIJA could accomplish for transit here.)

However, this funding alone was not enough. Ridership still hasn’t returned to pre-pandemic levels, and workforce shortages have only applied additional stress. Some local and state leaders also misinterpreted the new influx of federal cash as an opportunity to cut back on their own spending on transit, further delaying the recovery.

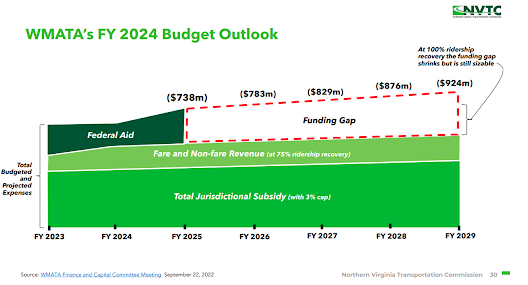

These combined stressors have created the transit fiscal cliff: the operating budget deficit expected at transit agencies across the country once their federal relief runs out. And for many transit agencies, the cliff is coming very soon—in some cases, as early as next year.

How bad is it?

The National Campaign for Transit Justice (NCTJ) and T4America conducted a sample survey to paint a picture of the fiscal health of transit agencies around the United States as they approach the two-year anniversary of the last emergency relief package. In an effort to hear from a representative sample, we contacted about 40 transit agencies across the country, operationally diverse in size, around the country.

Out of the agencies we contacted, we received 27 responses. Here’s what we found:

1. Urban ridership recovery lags behind rural ridership.

We started our analysis by separating agencies into groups based on geographic area. 5 survey participants serve rural populations, 19 participants serve urban populations, and 4 participants serve both rural and urban populations.

While there is a broad range, the majority of urban transit agencies report recovery levels lower than 75 percent of pre-pandemic levels. Rural agencies reported a range of ridership recovery as low as 60 percent and as high as 90 percent. Meanwhile, jurisdictions that serve both rural and urban populations hovered near the top, reporting ridership around 80 percent of pre-pandemic levels.

Increased workplace choice might explain the slow ridership recovery in urban areas. Workers who have greater workplace choice could have the option to work remotely and no longer rely on public transit to commute. We also found that urban riders are experiencing less reliable service due to workforce shortages. Service reliability is imperative to workers dependent on public transportation, and a lack of reliability could push riders to other travel options.

2. Most agencies are experiencing workforce shortages.

Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, workforce shortages have been a major issue across sectors, including public transportation. We knew that the agencies participating in our study might be experiencing shortages, but we were unprepared for the prevalence of workforce issues.

Of our 27 participants, 24 continue to experience workforce shortages, starting when the pandemic began. Some agencies are short over 800 operators and maintenance workers who are vital for the day-to-day operation of transit agencies. As a result of the limited personnel, some agencies have had no choice but to cut service.

To address these shortages, agencies are working to incentivize workers to join their team. See this blog post for more information on their efforts.

3. Two-thirds of transit agencies predict budget deficits by 2025.

We separated participants into three groups based on their timelines for expected operating budgets. An overwhelming majority of transit agencies expect budget deficits with start dates rapidly approaching. Transit agencies began running out of funds as early as Fiscal Year 2022, and only 5 of our 27 participants didn’t project an operating budget deficit.

10 out of 27 projected deficits starting in Fiscal Year 2024, and an additional 10 projected deficits starting in Fiscal Year 2025. Only 3 transit agencies projected operating budget deficits starting in the Fiscal Year 2026 or later and expected funds to last long term without intervention.

4. Transit agencies are implementing unique tactics to address budget shortfalls.

Participants varied in how they plan to address their deficits. Seven participants plan to increase fare prices, five plan to cut services, three are discussing ballot measures to increase funding, and the remaining are looking at solutions unique to their situations. One agency is looking to change service hours to reflect new traffic patterns. Another is looking to create a coalition of local businesses and institutions to philanthropically support the transit system, which would help replace missing fares.

It’s clear that transit agencies know the fiscal cliff is coming, and they’re not turning a blind eye. To continue delivering the service communities need, these agencies are offering creative solutions, showing a steadfast commitment to the operation of public transportation.

Help transit succeed

The Stronger Communities Through Better Transit Act (H.R. 3744), sponsored by Congressman Hank Johnson of Georgia, would allocate $20 billion annually to transit agencies’ operating budgets for four years, starting in FY23. The additional federal funding would empower agencies to make significant improvements to transit service. This could mean providing additional service or developing services for underserved communities. You can show your support for this legislation by calling your congressional representatives.

In addition to calling for federal funding, you can contact your state legislators and tell them to support similar legislation at the state level. In some states, that may mean advocating for constitutional and statutory changes that would allow the state to provide funding support for transit and alternative modes of transportation.

Another way to advocate for transit is by getting involved with your local government meetings. Providing feedback for members of local government is an integral step in improving transit service.

For too long, transit agencies have struggled to provide necessary service to our communities. So that all Americans are able to take advantage of this valuable resource, transit agencies must be given the support they need to deliver quality, reliable service.