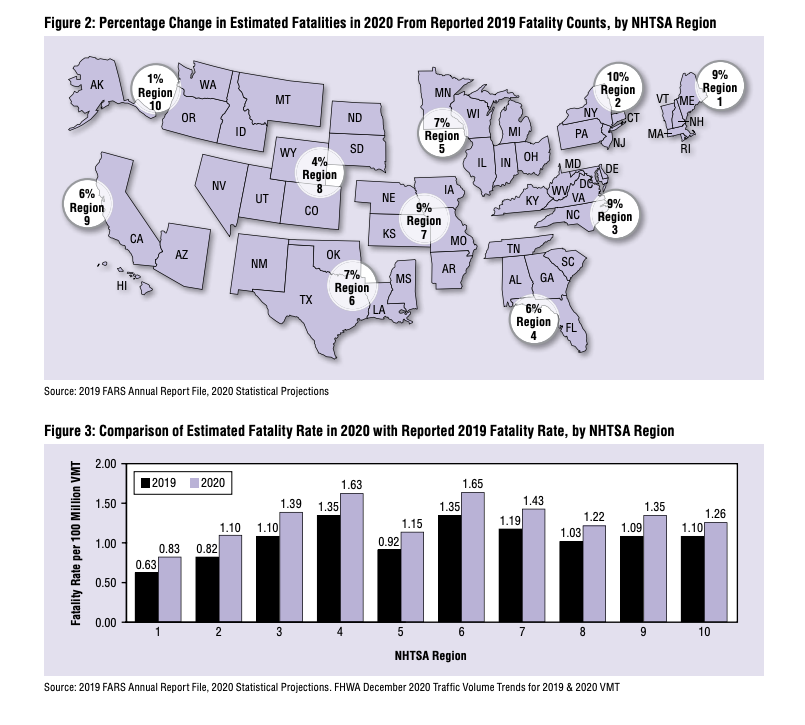

Driver expectations, higher speeds resulting from less congestion, major gaps in infrastructure, and a systemic criminalization of pedestrian and cyclist traffic on the road have contributed to the alarming, record increases in the deaths of people struck and killed while walking or biking, according to researchers.

Whether for recreation or simply to get from point A to point B, Americans have been walking and biking more, and thanks to COVID-19, this pattern has only intensified.

As more people walk and bike, we’ve also seen a historic increase in the numbers of people struck and injured or killed by vehicles while walking or biking. Researchers have been delving into this worrisome trend and the factors that may be contributing to this pattern, and at the same time, municipalities are rethinking their roadway safety or Vision Zero strategies.

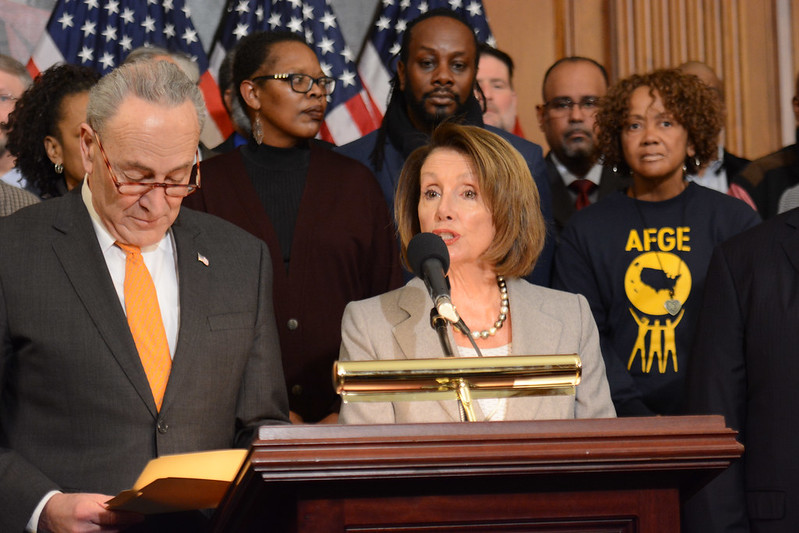

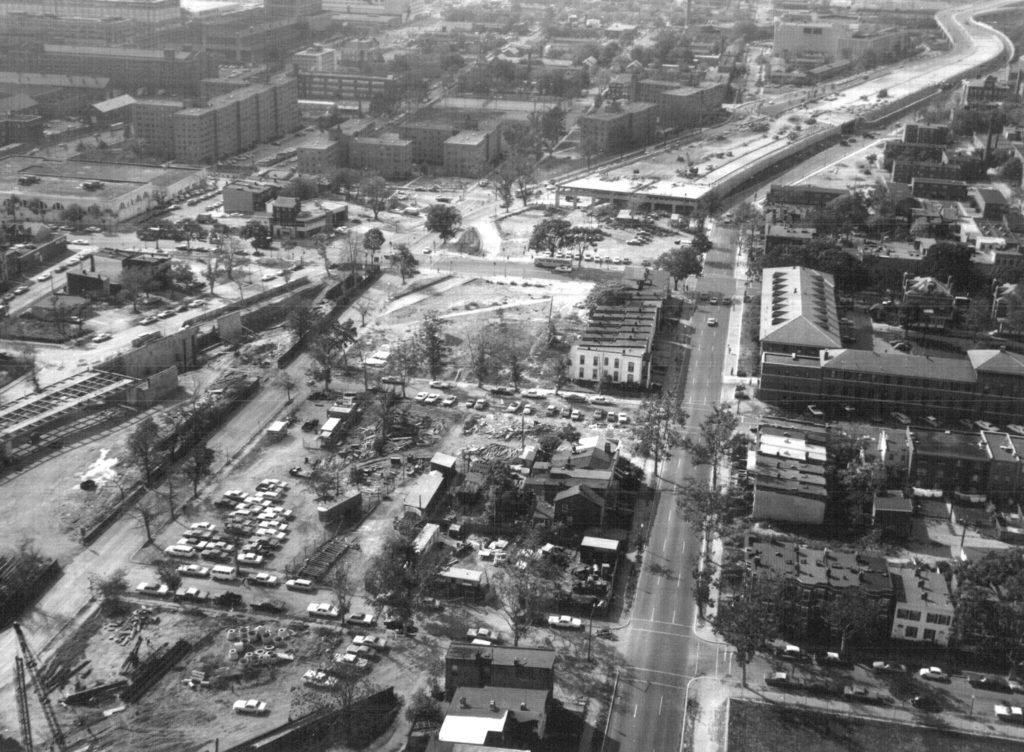

Photo on left: An open street in Georgia. Photo by Joe Flood via Flickr.

Research out of the University of Toronto highlighted a worrisome trend of drivers failing to acknowledge cyclists or pedestrians, especially at turns and intersections. “The results were quite surprising,” said Professor Birsen Donmez. “We didn’t expect this level of attention failure, especially since we selected a group that are considered to be a low crash-risk age group…. Drivers need to be more cautious, making over-the-shoulder checks, and doing it more often…. The takeaway for pedestrians and cyclists: drivers aren’t seeing you.”

They go on to postulate that there is an increased intensity and diversity of demands for drivers’ attention, including signage, diverse modes of transport and their evolving technology, and the presence of more cyclists and pedestrians. (Others have noted that the increase in deaths was coupled with increases in speed overall during the first half of the pandemic as streets emptied out, showing the connection between speed and greater numbers of deaths.) This demand for attention is at odds with the complacency of drivers, many of whom are not accustomed to having to worry about pedestrians and cyclists, and now they’re struggling to adjust. Making matters worse, the pedestrian and cyclist infrastructure that could clue drivers into the need to make room on the road is inconsistent, making it harder (not easier) for drivers to recognize when they’re sharing the road.

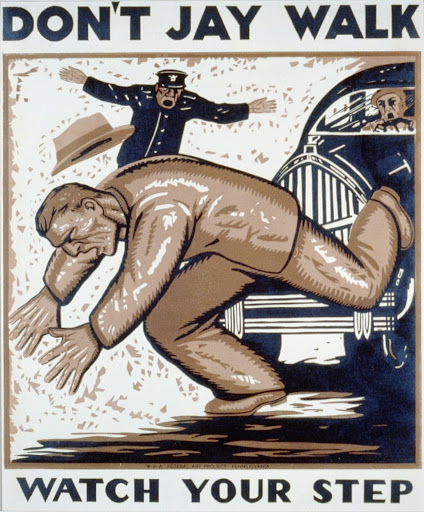

The need for consistent pedestrian and cyclist infrastructure is a twofold problem. One, roadway design and transportation policy makes safety and convenience for cyclists and pedestrians secondary to the auto, and at times, normal cyclist and pedestrian behavior is deemed outright illegal, according to Peter Norton’s book Fighting Traffic: “In the early days of the automobile, it was drivers’ job to avoid you, not your job to avoid them…. But under the new model, streets became a place for cars — and as a pedestrian, it’s your fault if you get hit.”

This encourages false assumptions about what belongs and what doesn’t belong on our roadways; as if streets aren’t meant to be shared with other users. If drivers assume pedestrians and cyclists shouldn’t be in the road, they’re less likely to be on their guard.

Image on left: An anti-jaywalking poster created in 1937. From Wikimedia Commons.

Secondarily, according to research by J. M. Barajas‘, the existing engineering, education and enforcement approaches to Vision Zero do not address the root of the issue with pedestrian and cyclist traffic fatalities that are overrepresented by people of color. This disproportionate impact is the result of a failure to invest in safe bike and pedestrian accommodations in marginalized communities.

Simply adding bike lanes and sidewalks won’t be enough. Safety from crime is another issue of concern for people of color, who often opt to travel on higher visibility corridors, which is where bike lanes and sidewalks are rarely considered because of the impact on the traffic engineers’ sacred cow of vehicle speed. Instead, this necessary infrastructure is more commonly placed on low-volume roadways, which have less public visibility. And for those who do bike, they are subject to police harassment, as cops are more likely to stop Black cyclists than white cyclists.

Since the spike in traffic deaths during the pandemic, pedestrian and cyclist fatalities are getting more visibility. The way we respond to this issue matters. Will we continue to push for only more ineffectual traffic enforcement, which disproportionately harms people of color? Will states and localities continue to push education campaigns that do nothing to address the root causes of driver inattention? Will we finally address unsafe designs as a primary culprit? Under the infrastructure bill, we could easily turn up the dial on these failing approaches and claim progress, even as fatalities continue to worsen.

What pedestrians and cyclists really need isn’t more tickets for jaywalking or lectures about wearing reflective gear. They need infrastructure that consistently makes room for them, prioritizes their safety and comfort above vehicle speed, and that provides greater visibility for all road users when they do mix with traffic, so that when drivers need to share the road, it doesn’t come as a surprise.