Rhode Island’s first ever statewide transit ballot measure would issue $35 million in bonds to invest in the state’s transit infrastructure and improve bus service statewide, including new and reworked transit hubs to bring together different modes of travel.

The transit bonds (Question 6) are part of a larger $275 million package backed by Governor Chafee. The money would largely be invested in building and modernizing existing and new transit hubs — with a primary focus on building a statewide multi-modal transportation center adjacent to Providence Amtrak Station, the 15th busiest station in Amtrak’s national network and the 3rd busiest station in the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority’s commuter rail network. And it could serve as a source of local funds required to “match” most federal grant programs as well as for leveraging private investment, helping bring even more transportation investment into the state.

Credit: Jef Nickerson on Flicker

Currently, there are few direct connections from one transit system to another in Providence. Building the hub will eliminate an inconvenient walk outside in the elements to get from the bus to the train, making travel and connections much more convenient and efficient.

Local and statewide business officials have identified improving the state’s transportation and infrastructure system as a necessity for staying competitive in the future.

Michael Lewis, director of the Rhode Island Department of Transportation, told the Providence Journal, “In any urban area, in any city, any state in the country, your transportation systems are critical to the economic health and vitality of any region.”

Even though most work is focused in Providence, these connections will expand access at key points throughout the state, says Lewis, including a complete re-vamp of RIPTA, the state bus system.

Having local dollars to match federal funds is a requirement for most federal grant programs like TIGER, and it can also help bring in other investment.

“This bond issue is going to enable Rhode Island to bring money to the table to leverage federal and private dollars so we can create the kind of transit system that’s going to make Providence and Rhode Island competitive,” Lewis said in an interview with WPRI News.

The “Move RI Forward – Yes on 6” campaign is spearheaded by Grow Smart RI and includes 63 members including the local and statewide chambers of commerce, businesses, construction and real estate companies, environmental organizations and even the American Automobile Association Southern New England. Scott Wolf, the executive director of Grow Smart RI and spokesperson for the “Yes on 6” campaign, said, “We believe a stronger transit system will attract new businesses and talented workers to Rhode Island, while also creating badly needed construction jobs, reducing congestion, and improving our air quality and our overall environment.”

Supporters argue that to stay competitive with other midsized cities such as Indianapolis and Eugene, Oregon, the state must attract and retain high-growth companies and highly talented workers. Wolf says Providence isn’t able to do that without the “boost to our public transportation system that this bond would provide.”

In September Rhode Island was awarded a $650,000 TIGER Grant to begin designing the multi-modal transit center, helping lay the groundwork to make these future bond dollars go as far as possible.

While there has been no organized opposition to Question 6, the Rhode Island Center for Freedom and Prosperity is against the bond package as a whole, arguing the state can’t afford to take on more debt.

“We start programs, the feds fund it for a limited period of time, the federal funding goes away,” said Mike Stenhouse, a member of the R.I. Center for Freedom and Prosperity. “We’re stuck with maintaining or keeping up payments that were started.”

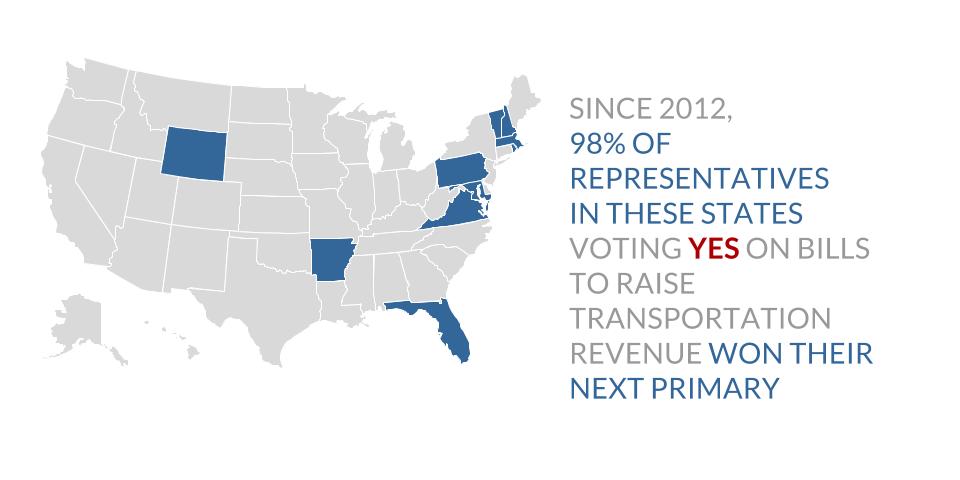

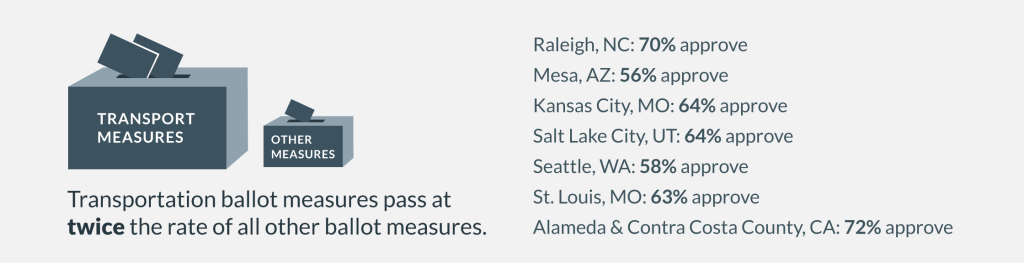

Rhode Island is just one in a series of states looking to voters to approve greater investments in their transportation system. For more information on important ballot measures being decided this November, make sure to check out our full Transportation Vote 2014 page.

To better serve the states and localities that are currently campaigning (or hope to campaign) for smart transportation investments, we are hosting the Capital Ideas Conference in Denver on November 13-14th. There’s still time to register for this event.

To better serve the states and localities that are currently campaigning (or hope to campaign) for smart transportation investments, we are hosting the Capital Ideas Conference in Denver on November 13-14th. There’s still time to register for this event.

If you’ve been working on a transportation measure as part of a funding campaign, working to overcome a legislative impasse, or defending a key legislative win, this conference will offer a detailed, interactive curriculum of best practices, campaign tactics, innovative policies, and peer-to-peer collaboration to help your initiative succeed.