DATE EFFECTIVE: FEBRUARY 17, 2017

[FEDERAL REGISTER NOTICE, HERE]

Overview

Less than one year after the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) first proposed outdated measures of congestion (see T4America’s blog post here) and after thousands of our members and partners provided comments, FHWA is now finalizing this rule. Published on January 18, the final rule rolls back some of the redundant, vehicle-focused measures initially proposed in the notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) and incorporates some significant changes, many of which we advocated for.

In response to comments from T4A and others, the final rule adds two new measures – a carbon dioxide emissions measure and a multimodal measure. To better reflect the number of people traveling on the system, two of the other proposed measures were modified so they are based on person-travel instead of vehicle travel.

In addition, the faulty measures for percentage of the interstate freight mileage uncongested and Peak Hour Travel Time Reliability (PHTTR) included in the NPRM were both deleted from the final rule. The final rule also simplifies the required data processing and calculation of metrics.

While the final rule is much improved, changes to the speed thresholds for the congestion measure may have some negative impacts on signalized downtown roads with low speed limits.

Background

On the same day that FHWA released this final rule on system performance and congestion, FHWA also released its final rule establishing regulations to assess pavement and bridge conditions. (See T4America summary here). These final rules are the last of several regulations issued to implement the performance management framework established by the recent national transportation authorizations bills, known as MAP-21 and the FAST Act.

In addition to these two rules, FHWA published rules on safety performance measures and the integration of performance management into the Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP) in March 2016 and published a rule on asset management plans in October 2016. In May 2016, both FHWA and FTA published a joint rule implementing changes to the planning process.

Together these rulemakings establish regulations for state DOTs and MPOs to evaluate and report on surface transportation performance across the nation.

Final measures

In the draft rule, 7 of the 8 proposed measures were based on vehicle travel time data. Now, only four of the final measures are derived from vehicle travel times, three of which are weighted to reflect all people traveling on the system.

The seven measures established in the final rule include:

- Three measures of system performance

- Percentage of reliable person-miles traveled on the Interstate

- Percentage of reliable person-miles traveled on the non-Interstate NHS

- Percent change in CO2 emissions from 2017, generated by on-road mobile sources on the NHS

- A measure for freight movement on the Interstate system

- Average truck travel time reliability index (TTTR)

- Three measures to assess the CMAQ program, including two measures on traffic congestion

- Total emission reductions for applicable criteria pollutants, for non-attainment and maintenance areas

- Annual hours of peak hour excessive delay per capita

- Percent of non-single occupancy vehicle (SOV) travel, including travel avoided by telecommuting

Timeline and enforcement

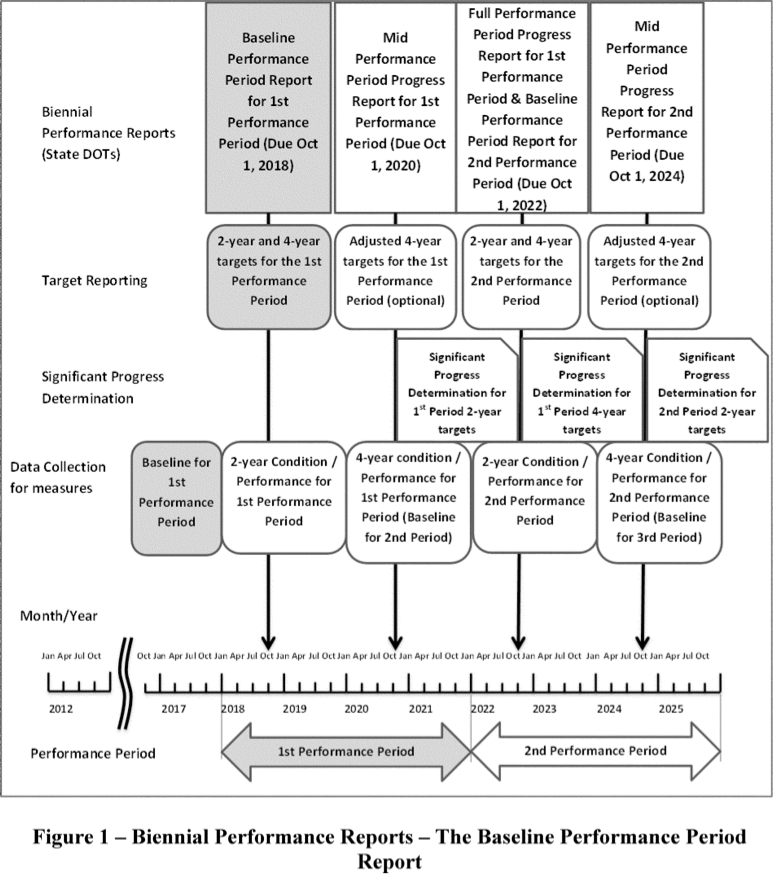

State DOTs will establish their first statewide targets one year after the effective date of this rule, February 17, 2017. MPOs have up to 180 days after state DOTs establish their targets to establish their own targets.

State DOTs must establish both 2-year and 4-year targets. The MPOs are subject only to a 4-year target-setting requirement. MPOs must either: (a) agree to plan and program projects so that the projects contribute toward the accomplishment of the relevant state DOT target for the performance measure, or (b) commit to a quantifiable 4-year target for the performance measure for the MPA. FHWA will assess every 2 years to determine if a state DOT has made significant progress toward achieving their targets.

If States/MPOs fail to meet their targets after 4 years, they have to set new ones for the next 2- and 4-year performance period. If they fail again, there is no real consequence.

Under the new administration, the White House ordered a freeze on the regulatory process. For regulations that have been finished but have not taken effect, the order calls for temporarily postponing their effective date for 60 days or possibly longer. This order could delay the effective date of this rule.

System performance

In the NPRM, FHWA proposed calculating performance on the interstate and non-interstate system by using two metrics: (1) Level of travel time reliability (LOTTR), and (2) Peak hour travel time ratio (PHTTR).

T4America and others expressed concern about the PHTTR measure as a poor measure of performance because it assumes the goal is for roadways to operate in free flow conditions at all times of day – a prohibitively expensive and infeasible goal that can undermine local economic development and multimodal travel. There was already another congestion measure under the CMAQ program and a different reliability measure looking at how consistent travel was from one day to the next. Due to this, we recommended that this measure be vacated, which FHWA did in the final rule..

The final rule also changes the weighting of the travel time reliability measures from system miles to person-miles traveled using overall occupancy factors from national surveys. This prioritizes roadways that move more people through carpooling and transit over roads that only move SOVs.

New CO2 emissions measure

The final rule adds a new emissions measure – percent change in tailpipe CO2 emissions on the NHS from calendar year 2017. This measure applies to the NHS in all states and metropolitan planning areas. All state DOTs and MPOs that have NHS mileage in their state geographic boundaries and MPAs will be required to establish targets and report on progress.

State DOTs will calculate the measure by multiplying motor fuel sales volumes by the FHWA-supplied emissions factors of CO2 per gallon of fuel and percentage VMT on the NHS.

Freight movement on the interstate

The draft rule proposed two measures of freight movement on the interstate: (1) Truck Travel Time Reliability (TTTR), and (2) percent of the interstate system mileage uncongested. T4A and our partners were concerned that the TTTR measure would prioritize freight movement over the movement of people. In response, FHWA removed the TTTR measure from the final rule.

FHWA also changed the form of this measure from one based on the percent of the system providing for reliable travel to an overall average truck reliability index for the Interstate. This change removes the hard threshold in the definition of reliable travel for trucks and recognizes incremental improvements that could be made to improve reliability.

CMAQ program

Three measures are established for the CMAQ program, including total emissions reduction measure and two traffic congestion measures.

Traffic congestion

The NPRM proposed measuring traffic congestion under the CMAQ program by looking at annual hours of excessive delay per capita. As mentioned above, a separate peak hour travel time reliability (PHTTR) measure was also proposed for measuring system performance on the interstate and non-interstate systems. The PHTTR measured percent of the interstate system in large urbanized areas over 1 million in population where peak hour travel times meet expectations. These two measures merge in the final rule creating the Peak Hour Excessive Delay (PHED) measure.

In response to comments, a new multimodal measure – percent of non-SOV travel – was also added in the final rule.

APPLICABILITY

Both the PHED and the multimodal measure adhere to the same applicability requirements. As proposed, the CMAQ congestion measure applied to areas in nonattainment with a population over 1 million. The final rule expands applicability to also include areas with a population over 200,000.

The applicability of both CMAQ traffic congestion measures will be phased in, beginning with urbanized areas with a population over 1 million that contain any part of nonattainment or maintenance areas for one or more air pollutants in the first performance period (2018). It will be expanded to urbanized areas with a population over 200,000 that contain any part of nonattainment or maintenance areas for one or more air pollutants beginning in the second performance period (2022).

The final rule also moves up the date of measure applicability determination to one year earlier than initially proposed. FHWA will determine measure applicability based on the most recent available data on October 1, 2017.

PHED – SPEED THRESHOLD

As proposed in the NPRM, the traffic congestion measure would have established a 35 mph threshold for freeways and a 15 mph threshold for other NHS roadways. In the final rule, FHWA responded to concerns about these static speed thresholds by setting the excessive delay threshold to 60 percent of posted speed limit, with a minimum limit of 20 mph. This may be a slight improvement for measuring excessive delay for expressways, but this same threshold will also apply to non-expressway facilities. Particularly when applied to signalize urban roads marked at 25mph, vehicle speeds might fall below 60% of the speed limit even during free-flow conditions.

In the final rule, FHWA encourages state DOTs and MPOs to share their strategies using volume limiting techniques to address concern when extremely slow speeds exist. FHWA plans to make provisions within HPMS to capture posted speed limit data by adding a field that can be populated for the full extent of the NHS.

PHED – PEOPLE-CENTRIC CHANGES

FHWA agreed with comments that the measure should represent the cumulative delay of all people using the NHS and not just the delay experienced by vehicles. As a result, the PHED measure requires the use of average vehicle occupancy (AVO) factors for cars, buses, and trucks and hourly traffic volumes to calculate person-hours of excessive delay. To support this approach, FHWA will establish AVO factors for applicable urbanized areas using the National Transit Database for buses and national surveys, such as the American Community Survey, for cars. State DOTs and MPOs have the flexibility of choosing to use these AVO factors or substituting more specific AVO data that they may have.

In response to comments, including comments from T4A, the final rule requires the use of annual population estimates using U.S. Census estimates (i.e. most recent ACS 5-year estimates) as opposed to the decennial census populations to normalize the excessive delay measure. The most recent annual population estimate will be used each time the PHED per capita measure is calculated.

PERCENT OF NON-SOV TRAVEL

This measure includes modes that are in the ACS Journey to Work data, which includes travel avoided by teleworking. State DOTs and MPOs have three options for calculating modal share:

- use the ACS Journey to Work mode share data

- use locally specific surveys, or

- use volume counts for each mode.

FHWA encourages state DOTs and MPOs to report data not currently available in national sources, such as pedestrian or bicycle counts. For state DOTs and MPOs that chose to use count data, FHWA encourages this data to be voluntarily submitted to FHWA via national sources or databases (such as TMAS, NTD, or GTFS-RT).

On-road mobile source emissions

APPLICABILITY

While FHWA acknowledged T4A’s comments, FHWA did not agree that this emissions measure should apply more broadly to include all states or regions that receive CMAQ funds, or to consider all capital and operational opportunities to reduce emissions, not just those that receive CMAQ funding.

The measure is applicable to all states and MPOs with projects financed with funds from the CMAQ program, apportioned to state DOTs for areas designated as non-attainment or maintenance for ozone, carbon monoxide, or particulate matter. FHWA clarified in the final rule that the baseline non-attainment and maintenance area designations should be based on area status as of October 1, 2017.

FHWA narrowed the definition of ‘maintenance area’ to exclude any areas that have completed their 20-year maintenance plan for an applicable pollutant. States and MPOs can also request exclusion from this requirement at the midpoint of the performance period, if their designation changes (i.e. the 20-year maintenance plan is achieved, or the area is no longer designated as non-attainment or maintenance).

While state DOTs and MPOs can still use CMAQ dollars to fund projects where is it not possible or easy to quantify the emissions benefit, these projects will not be accounted for in this performance measure.

METRIC & TARGET ADJUSTMENT

The final rule removes the conversion from kilograms per day emissions data to tons per year data. The final rule calculates total emission reduction as cumulative reductions in emissions over 2 and 4 federal fiscal years.

As in the proposed rule, the final rule allows states or MPOs that believe they would not be able to meet a target due to a change in models to adjust the target at the performance period’s mid-point or explain in their final performance report why they were unable to meet their targets due to model-based emissions estimate.

TIMELINE

Consistent with CMAQ Program Guidance, state DOTs must enter their CMAQ project information for the previous fiscal year into the CMAQ Public Access System by the March 1 deadline. In this rule, FHWA adds a new July 1 deadline, for when all information must be in the CMAQ Public Access System. This due date will apply on July 1 after the final rule is effective.

States and MPOs must use projects in the 4 years prior to the first performance year as a basis for establishing a target for the first performance period. The projects entered into the CMAQ Public Access System during the 2-year and 4-year performance period will be taken as is to calculate the measure.

Additional measures

FHWA notes that state DOTs and MPOs may voluntarily report additional measures beyond their baseline requirement. Additional measures, or variations, could include metrics for per capita emissions, VMT-based estimates, or other useful indicators. Some of the priority outcomes not addressed by the Congressionally mandated measures promulgated by this rule are jobs access, freight movement off the Interstate, public health, stormwater runoff, and household transportation cost.

Review & analysis

FHWA will review this rule after the first performance period to assess effectiveness of the requirements and identify any necessary changes. FHWA also plans to revisit the reliability and congestion measures after the completion of its multimodal research study in Fall 2018.

USDOT made significant improvements in this final rule. However, the ability to set negative targets (e.g., a target of more fatalities) remains an area of concern as does the lack of real accountability for failing to meet any of the self-set targets. This is a flaw in the underlying legislation and not anything FHWA could have addressed in the rulemaking.

Furthermore, the progress made under this rule could be rolled back, if the new Congress overturns this rule under the Congressional Review Act (CRA). At a minimum, the effective date of this rule may be delayed for 60 days. T4America continues to monitor this rule and will provide updates as necessary.