After many decades of being divided by highways, community members in National City, CA are building capacity to reconnect their community in a project that will also acknowledge their community’s heritage and future.

The National City Southeast Greenspace Corridor Project is receiving support from the Community Connectors Program, led by Smart Growth America in collaboration with Equitable Cities, the New Urban Mobility Alliance, and America Walks with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Learn more about the Community Connectors Program.

Often romanticized in the media, Southern California has been the home and the template for the modern US highway that we know today. Media portrays these highways as facilitating economic growth and safer and speedier commutes for area residents. However, the underbelly of that media portrayal fails to acknowledge the divisiveness those highways create, separating communities, destroying cultural and economic assets, and exposing many vulnerable road users to deadly conditions.

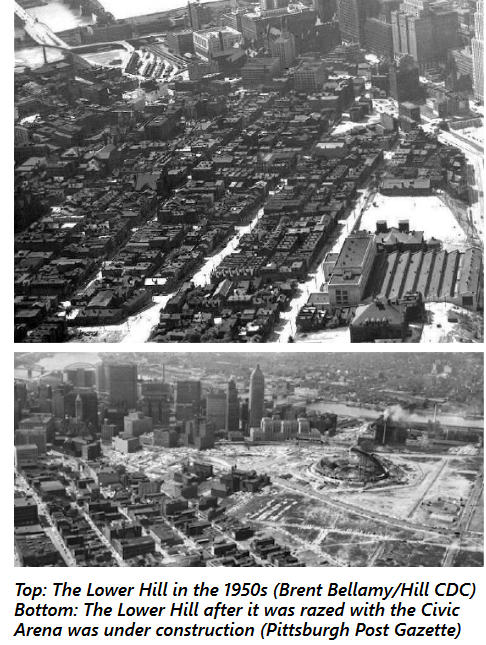

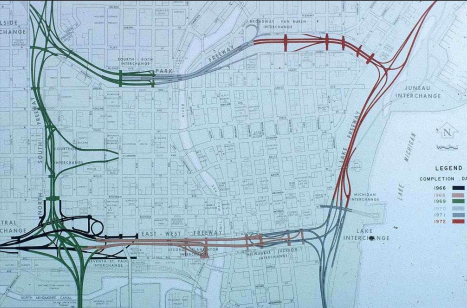

However, Southern California, especially the greater San Diego region, didn’t have divisive highways when those communities were initially developed. For San Diego and the greater Southern California region, one only has to look to the Robert Moses of the West, Mr. Caltrans, Jacob Dekema. Dekema came to the San Diego region in 1955 as its first Caltrans district director. At the time, the region was home to only 25 miles of highways. When Dekema retired in 1980, he had overseen that network growing into 485 miles of highways and entrenched a culture dependent on the car.

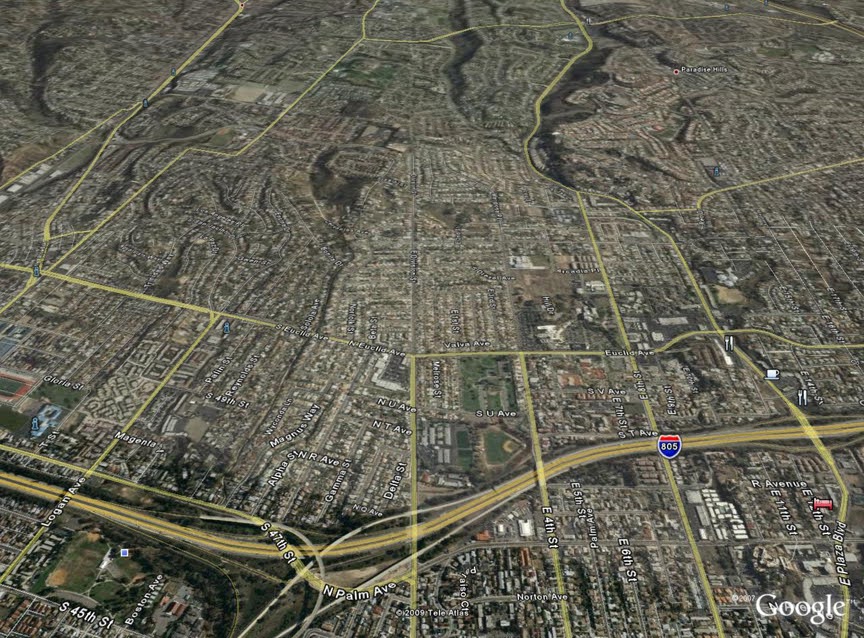

One of those communities in the shadows of, and sliced by the intrusive, life-sized sculpture dedicated to the car, is National City, CA. This diverse community of 56,000 as of the 2020 census, had its community sliced and diced by the sprawling highway creation. I-5 divides the city from it’s waterfront to the west, and I-805 runs through the heart of the city’s east side.

The 805, like many highways across the country, came into consciousness around 1956, with its construction in the late 1960s that wrapped up by 1975. Parallel to the highway’s construction, efforts in National City in 1969 revisited zoning to facilitate auto-oriented strip mall development, further setting up a concrete jungle for residents.

The most disruptive and obsolete highway construction for I-805 is Exit 11A. This exit was built to facilitate a highway to future highway transfer (what was to be known as the El Toyon Freeway or SR-252). Through intense community advocacy and opposition, the Toyon Freeway project was canceled in 1980 and removed from consciousness in 1994. However, Exit 11A remained, today serving as the 43rd Street exit, which drops a driver off at the auto-oriented Southcrest Park Plaza.

Seeds of a movement

The multicultural tapestry that connects National City and Southeast San Diego (SESD) today has been left with a disproportionate share of challenges. The community lacks green space, has high levels of diesel particulate matter exposure, faces transportation barriers (due to the intricate web of highways around it), plus more and bigger cars zooming by community streets. These challenges have eroded the community’s quality of life, health outcomes, and well-being, particularly for those living in low-income households.

There is considerable acreage lying fallow under the shadow of the 43rd Street ramp. The land under the freeway occasionally is used by Caltrans as a highway maintenance and operations storage space, but otherwise remains a living scar for the community, overlapping National City and Southeast San Diego and preventing them from being fully connected to their fellow neighbors. With the economic decisions made in the 1960s, economic development opportunities remain poor in the area, with value generated in the area not fully captured and invested back into the community.

Even in the midst of an overbearing highway structure dividing various neighborhoods in northeast National City and Southeast San Diego, members of the community have worked to bridge infrastructure divides through cultural activities and streetscape beautification. One of those efforts, Joe’s Pocket Farm, has served as a catalyst for area advocates to push for a holistic community vision to reconnect the community.

Starting as a vacant land plot by I-805 and Division Street, Mr. Jose Nuñez cultivated a pocket garden near his home for many years before moving away from the area in 2008. This pocket garden fell into disrepair and turned into a dumping ground until community members organized to save the garden and turn it into a community asset. In late 2009, community members engaged the National City City Council to reclaim the vacant and dilapidated garden into what is today the Joe’s Pocket Farm. This advocacy and organizing ultimately led to the creation of a local-area nonprofit, community garden, and social justice organization, what is Mundo Gardens today, which is aimed at empowering youth and community members on cultivating solutions to address social determinants of health.

Not long after Mundo Gardens’ founding, the Urban Collaborative Project (UCP) was formed. Created in 2013 as a nonprofit organization serving redlined communities in National City and Southeast San Diego, UCP leverages a data-driven, community self-healing approach to tackle key issues, including building social infrastructure and capital, transportation and infrastructure equity, health disparity and environmental justice, cultural beautification, and housing and community development.

Developing and executing a community vision

Mundo Gardens and UCP are pieces of a larger community-driven movement that has been in the making over the past two decades on reconnecting their community and mitigating social determinants of health. Community conversations have scoped out the Greenspace Corridor Project, which would unify National City and Southeast San Diego through reforestation, cultural art, and community. This project aims to accomplish various tasks, including but not limited to, 1) dismantling the 43rd Street exit ramp from I-805 and the defunct SR-252 built segment, 2) creating a community park on the reclaimed highway land centered on community culture, community health, and the natural environment, 3) stimulate social equity investment in the community, and 4) reconnecting the greater community to its culture and heritage.

The National City / Southeast San Diego community coalition, which is advancing the Greenspace Corridor Project, has made great strides in building its community network, which now includes city staff from National City, Council of Equity Advocacy San Diego, Kumeyaay Community College, Tocayo Engagement, SANDAG staff, Caltrans District 11 staff, among others.

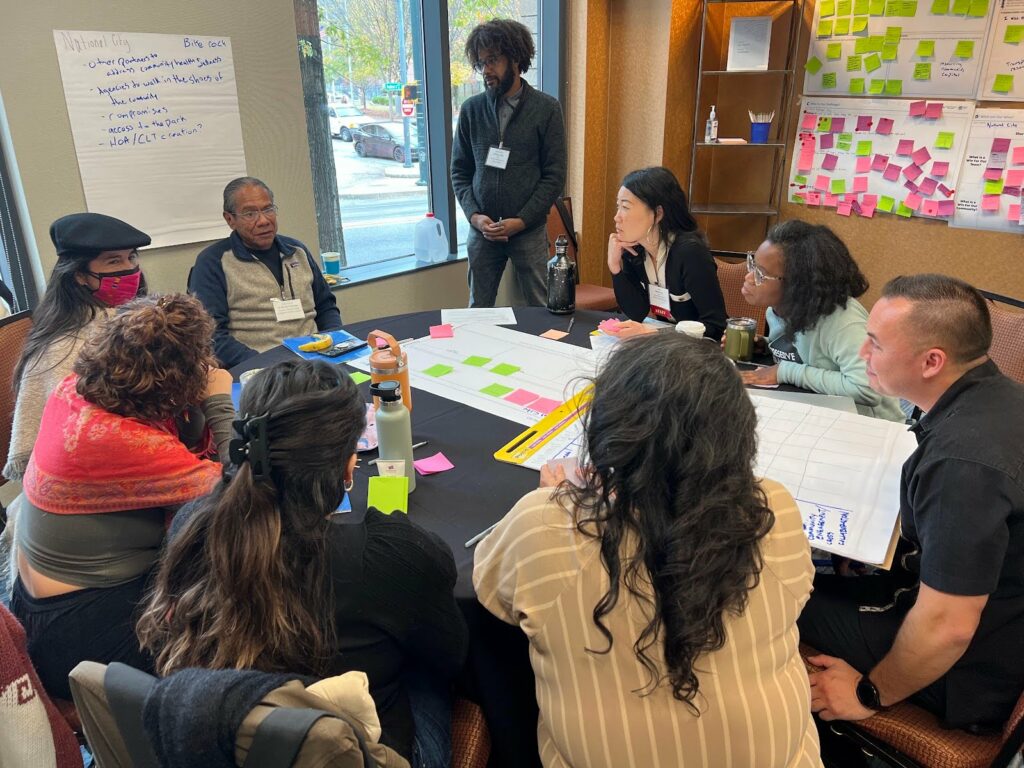

This coalition joins other community coalitions around the country selected in July 2023 to be part of the Community Connectors program. This program has allowed the National City / Southeast San Diego community coalition, alongside their peers, to access technical assistance and capacity building support to advance their community project. In November 2023, the coalition met alongside their peers in Atlanta for a Community Connectors convening. At that convening, the National City / Southeast San Diego community coalition was able to map out project challenges and possible wins, plus flesh out a preliminary implementation plan.

In March 2024, the community coalition received double good news: two major wins in their collective advocacy and outreach efforts to support and fund the Greenspace Corridor Project. On March 12, 2024, Caltrans announced the coalition as one of three grant winners of the state’s Reconnecting Communities: Highways to Boulevards pilot program, totaling around $50 million for planning and implementation efforts that advance the project. The very next day, USDOT announced the coalition also won a $2 million Reconnecting Communities & Neighborhoods Program planning grant.

Looking to the future

The Greenspace Corridor Project holds much promise with a strong and emboldened coalition that now has seed funding to actualize their project. However, the work is only beginning, as the coalition will now begin the figurative and literal cultivation of their community garden. Later in 2024, the National City / Southeast San Diego community coalition will organize and deliver a community convening aimed to advance the conversation held in Atlanta and more fully flesh out a project implementation plan. The coalition also aims to enhance community engagement, storytelling, and outreach to raise awareness on the project and broaden stakeholder support. Lastly, the coalition aims to continue to pursue additional local, state, and federal resources to realize the community park that is centered on community health, culture, and economic opportunity, expanding what started as a small pocket farm from the hands of Mr. Nuñez.