Visiting communities other than our own can remind us to envision more for transportation in our own communities. This is especially important now, with so much infrastructure funding starting to flow that could actually make these visions reality.

When people travel, they shed routines and become open to new experiences. They’re likely to use various modes of transportation from carshare services and bike rentals to exploring the nearby environment on foot. For me, doing so gives me a more complete experience of the place I am visiting, and I often learn something.

For example, I recently visited a U.S. city which has made major strides to improve its transit and biking infrastructure. To get around, my family took advantage of a great new train line and enjoyed biking on separated paths. But my kids were quite frightened when we struggled to make it across a gap in the bike network the day we rented bikes. In addition, two of my children were very nearly hit by a right-turn-on-red driver speeding through the right-turn-only slip lane and failing to stop on time as we crossed a busy arterial road with the walk signal and the right-of-way. I was impressed by some of the improvements, but appalled by the gaps in networks, which mostly existed on dangerously fast arterial streets with little improvement to make them safer for people outside of cars.

I’m not naming the city in question because that’s not the point. Instead I want to emphasize that the perspective of the outsider, or visitor, is so valuable in helping us to see the infrastructure of our own communities with fresh eyes and fresh perspectives.

So how can you get this sort of new or fresh perspective on the transportation options and infrastructure in your community? You might think about how a newcomer navigates your community, or even someone with different physical abilities or a different race. How would a blind person or someone in a wheelchair navigate this intersection? A child on a scooter? Do wide streets without adequate crossings result in speeding or jaywalking? Does enforcement on those streets fall disproportionately on Black community members?

There are great examples of people doing exactly this all over social media. Vignesh Swaminathan (or Mr. Barricade, as he’s known on social media), who joined us at Smart Growth America’s Equity Summit last January, uses Tiktok to explain how street design can better meet the needs of all members of the community.

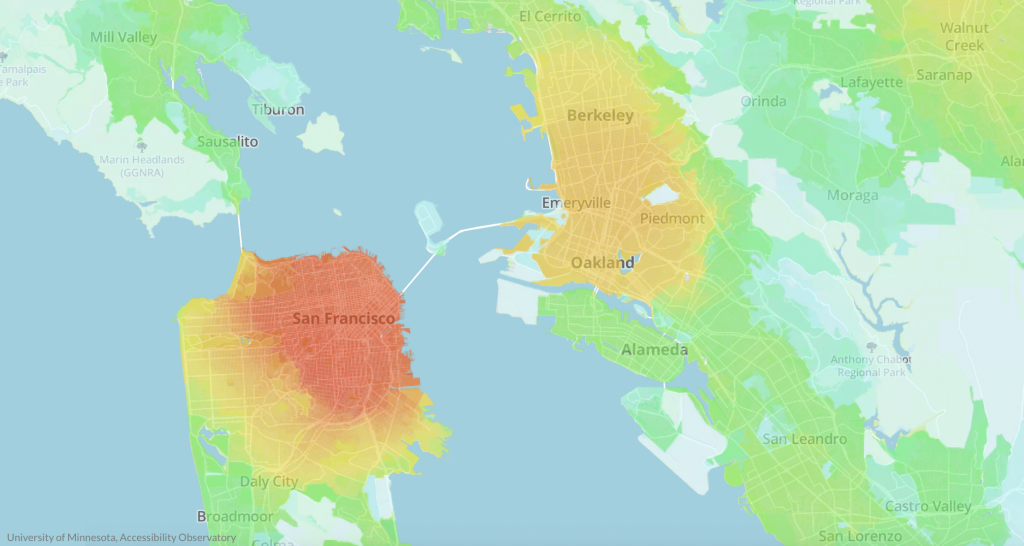

When you try to take on the perspective of someone different than you, or a visitor or tourist perhaps, and see your community with new eyes, you may see some of your successes (as Swaminathan often does), but you may also see the gaps in the network, confusing intersections and missing or confusing wayfinding. These are real barriers for your neighbors who may be thinking of trying out transit, biking or walking for the first time in their and your own community and people who are already get around in those ways. Maybe it renews your outrage at arterial streets that still lack safe bike infrastructure and safe pedestrian crossings, the longstanding gaps in the bike network, and the infrequent transit service.

Seeing your community’s infrastructure with this sort of “beginner’s mind” can help you better see how the status quo is failing to serve us. We’ve become so used to our transportation system being dangerous, inconvenient and expensive, that sometimes that terrible reality just fades into the background. But let’s face it. Aliens from outer space would give America’s transportation infrastructure a D- at best, and so would visitors, outsiders, and a lot of people living in the community that might be getting overlooked.

Try looking at your own community anew. If you travel, bring that fresh perspective back home and challenge the status quo in your own community. Take a walk audit. Talk to visitors about what they see. Reach out to decision makers to fill safety gaps, and stay wise to the strategies they use to deter change. Use our guide to implementation of the infrastructure law to think about how the infrastructure law’s historic funding can be spent to make transportation systems more accessible, safe, and intuitive.

We’re fighting a long fight and making incremental progress, but let’s not let go of making our transportation system truly great. We should imagine and fight for a time when the visiting alien analogy no longer works. It no longer works because we’ve built a transportation system that is so safe and sensible that anyone would be able to navigate it safely, without so much as a second thought.

Transportation is fundamentally about connecting people, but America’s transportation system focuses on moving cars instead. Madlyn McAuilffe from the

Transportation is fundamentally about connecting people, but America’s transportation system focuses on moving cars instead. Madlyn McAuilffe from the