New mobility services have enormous potential to change the transportation landscape and increase access for all residents. But, only a few projects are actually focused on that.

As new mobility models continue to have an impact on our transportation system and shift how our cities are designed and operate, cities and transit agencies are launching new pilot projects to test everything from microtransit to ridesourcing to automated vehicles and understand how these services can best function in and benefit their communities.

One of the most promising areas to capitalize on new mobility services is around increasing access for people most in need; people who live in areas that are currently underserved by transit, do not have bank accounts or cell phones, require wheelchair access, or commute during off-peak hours. Depending on how they’re deployed, these services could help community members more easily reach jobs, school, medical appointments, grocery stores, or wherever people need to go.

Many of these individuals are already dealing with a transportation network that has often been designed without their needs in mind—whether it’s infrequent transit, a lack of affordability, or inconsistent paratransit options. This has grown worse in recent years as many lower-income individuals, faced with the high cost of living, have been forced to move from city centers to inner and outer ring suburbs, with fewer jobs and resources and where reliable, affordable public transportation is even less likely to exist.

New mobility services have the potential to provide additional access to these communities, but have to be designed with those goals in mind. Often, projects across the country are sold on these outcomes, citing increased access to opportunity as a direct benefit, but simply piloting an automated vehicle shuttle or a microtransit service or setting up permitting processes for scooters or dockless bikeshare won’t produce these outcomes. Without careful deployment, these new services won’t help communities realize the potential benefits and could even exacerbate current inequalities.

For example, some cities have chosen to subsidize transportation network companies (TNCs) like Lyft and Uber to save money on fixed-route transit or used TNCs in place of transit altogether. While these experiments claim “improved access” as a benefit, few are designed with this as a primary goal or measurable outcome. In other cases, cities and transportation agencies design projects around the shiny new technology, next select a pilot area, and only then focus on the problem it could solve—the problem (and people being served) should come first.

For a city to truly solve its mobility challenges and actually create additional access for its residents, it needs to focus on its long-term outcomes, make thoughtful decisions about why and how it will deploy a new service, and understand how it will lead to those outcomes. This requires starting with a thorough understanding of the problems a community is facing, particularly its most disadvantaged residents, and then developing potential solutions from there.

We spoke to two communities that are currently running pilots designed to increase access to better understand how they developed their project scope, what their outcomes are, and where they think other cities and agencies could emulate their efforts.

Pinellas County, Florida—TD Late Shift

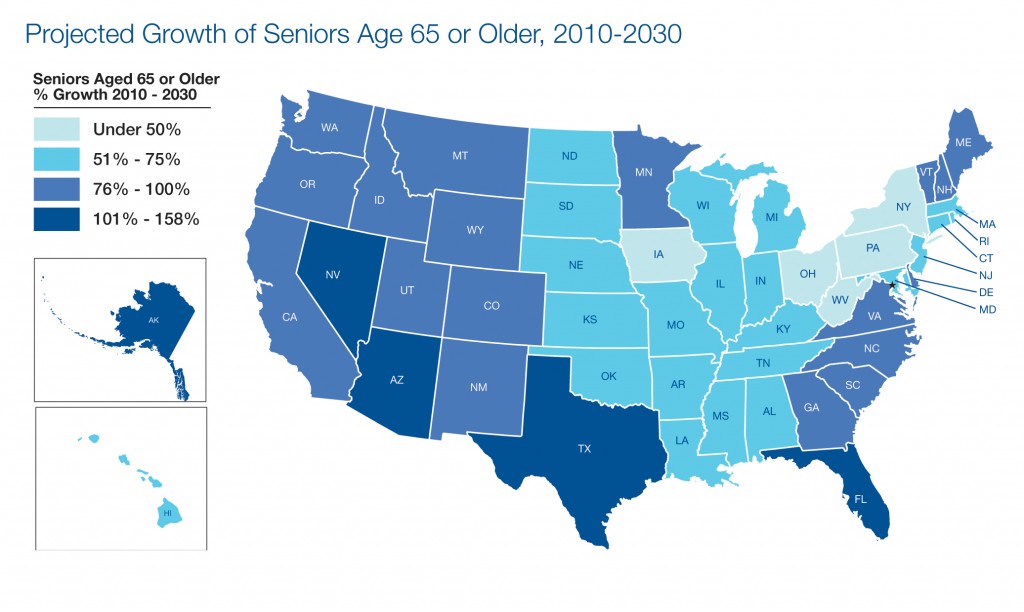

Pinellas County sits on Florida’s Gulf Coast, just west of Tampa, with a population of nearly one million. Given that beaches, tourism, and nightlife make up a major part of the county’s economy, a large share of local workers have hours that run late into the night or start early in the morning—when many transit services (including Pinellas County’s) don’t operate.

“We don’t have the density or funding to operate fixed-route service overnight, but we do have a lot of workers in the service industry,” said Bonnie Epstein, Senior Planner for Pinellas Suncoast Transit Authority (PSTA), the county’s transit provider. “We have beach bars and hotels and restaurants that stay open pretty late, so there’s a huge need for [additional] service.”

Understanding this challenge and with their problem clearly defined, PSTA launched the TD Late Shift pilot program in 2016. For $20 per month, many low-income county residents can purchase a monthly bus pass and also receive 25 free on-demand trips, through Uber, United Taxi, or Wheelchair Transport, to or from work anytime regular bus service isn’t running. The pilot is targeted at anyone who qualifies for the Transportation Disadvantaged (TD) program, a state-funded initiative. To qualify, residents must lack reliable transportation options and have a household income no greater than 150 percent of the federal poverty line.

Much of the thinking for TD Late Shift came out of PSTA’s Direct Connect Pilot, another ridesourcing project the agency launched earlier in 2016 that provides $5 discounts on rides to and from bus stops from the same providers as TD Late Shift. Direct Connect is open to anyone, but is only during regular transit service hours. After the Direct Connect pilot launched, the agency recognized that while it was increasing access during the day, late night and early morning commuters were still in need.

TD Late Shift was designed fill this need. According to Epstein, the goal is to improve job access by allowing people to work later shifts and know they can get to and from work, work additional shifts at different hours, and increase safety. Before the pilot, residents with late night or early morning hours didn’t have many options. “Some couldn’t get to work, some rode their bikes at 2am [often without adequate bike infrastructure], and some often had to wait late at night for someone to pick them up,” said Epstein. “With these on-demand, late night rides, residents have more time to spend with family, can sleep longer and are safer since they don’t have to wait outside late at night or walk or bike on potentially dangerous streets.”

So far, the program has proved popular as ridership has grown since its launch in 2016 and is slated to run through the end of June 2019.

Detroit, Michigan—Woodward 2 Work

The City of Detroit’s Department of Transportation (DDOT) launched a similar project in early May of this year that is also focused on increasing access for late shift workers. While Detroit does not have the beaches of the Gulf Coast, it has many residents working late shifts who lack reliable and safe door-to-door commuting options.

The Woodward 2 Work (W2W) pilot provides discounted Lyft rides to anyone going to or from an eligible bus stop on the Route 53-Woodward bus line. Route 53 runs 24 hours a day, beginning just south of Eight Mile Road at the northern edge of the city and connecting straight to the heart of downtown, an almost nine mile trip. DDOT chose Route 53 because of the large number of riders it could reach, especially those working later shifts.

To use the service, potential riders need to text “W2W” to the project hotline between 12am and 5am. In response, riders receive a code they enter into the Lyft app—or use over the phone through Lyft’s Concierge service—for a $7 discount on any ride.

This is the first partnership for DDOT with a TNC and the department wanted to make sure they got it right. Before the pilot started, DDOT conducted community outreach through surveys and personal interviews in order to clearly identify community challenges and build a project from those needs. “We didn’t want to pose a solution before defining the problem,” said Stacey Matlen, Senior Mobility Strategist at DDOT. “We knew there were a number of challenges for people walking to and from the bus stop at three in the morning, so we conducted interviews with late shift workers and created personal journey maps to understand everything these customers encounter.”

DDOT came up with a number of possible pilot ideas from the information they gathered during their outreach. Then, they took these concepts back to the community to see how well they might fit. “We saw that a lot of people were carpooling, so we thought about that [as a pilot], but received feedback from users through scenario testing that that’s not necessarily what either group of employees (riders and drivers) wanted,” said Kenny Fennell, also a Senior Mobility Strategist at DDOT. Through these conversations, DDOT developed W2W as a pilot that would make more sense with the community’s needs and desires.

Designing with access in mind

DDOT’s pilot is a great example of how cities can think about improving access from the ground up with the user’s perspective in mind and without a predetermined solution. Unfortunately, many cities develop pilot projects with a specific technology or service they want to deploy, such as automated vehicles or microtransit, and then go searching for problems it could solve. There is often no process of outreach and community engagement to determine how the service can best help improve access for their residents.

Instead of starting with a potential solution in mind, or a particular technology, PSTA and DDOT used a robust community engagement process to ensure the end user was involved from the beginning. They focused on their communities’ needs and put together a project that would best serve them.

With DDOT, the department made a clear decision from the start to bring these new services to the people who have the most to benefit from them. “To ensure equity, the design and decision making process should take into account how the most under-resourced user will be affected,” said Fennell. Matlen echoed this view, noting that “getting out of the building and interviewing stakeholders to know what their problems are and how our projects can help” is the most essential component of the process.

Both PSTA and DDOT did an excellent job of identify local mobility challenges, sourcing ideas from the community, and then designing an appropriate solution. For DDOT, the most important metric they’re tracking for the project is how many riders they’re getting to work and continuing to conduct interviews with riders in order to refine the pilot along the way.

With TD Late Shift, PSTA also designed the service specifically around the needs of its users that did not have access to fixed-route service or the Direct Connect pilot to get to work and made sure it was accessible for lower-income individuals, individuals without a bank account or credit, and wheelchair users. The agency has continued to learn from its efforts and has worked to continuously improve the pilot to better serve its users. As ridership continues to grow, PSTA is hoping to make it a permanent fixture of its service.

With both pilot projects, there are still plenty of questions over how best to gauge how well these pilots are meeting community needs, how they can improve service to include more riders, and how to more directly link them up to other long-term outcomes. But what’s most important is that they’re engaging with their communities to ask these questions and actively look for answers.