Investments and policies that support car travel at the expense of all other transportation options have helped create a culture of driving in the U.S. Investing in a variety of transportation choices, like opportunities to bike, walk, and take public transit, would improve safety and accessibility for all.

The ghost of walkable streets’ past

Before the car started to take off in the early 1930s, streets were for everyone. Wagons, walkers, bikers, horses, they all utilized the street to get to daily activities and destinations. Pre-Industrial Revolution Americans would walk between 10,000 and 18,000 steps per day, and high rates of walking and biking to work or school continued throughout the late 60s. Because the street was so widely used by many different forms of transport, it functioned as a public space, a place where children could play as much as cyclists could bike to the store.

When cars began rising in popularity in the 1920s, they entered a space not designed for them, posing a danger to other travelers. The public grew alarmed at rising death tolls and vehicle crashes, calling for reduced vehicle speeds and more protections from the car. Automakers, dealers, and enthusiasts flipped their narrative, advocating for legislation and funding campaigns that sought to regulate and restrict where people could walk and bike.

The latter campaign succeeded, but it didn’t make our streets safer. Instead, streets ultimately became a place where quick, convenient car travel is often prioritized over the safety and comfort of all other road users. In 2022, the number of people hit and killed while walking reached a 40-year high.

The illusion of choice

Post-WWII in the United States was a time of world-building, of focusing on creating a brighter future for the country in the aftermath of destruction. The infrastructure that came along with this shift made suburban lifestyles the ideal, and the car a symbol of freedom. A combination of economic incentives and a deprioritization of dense, mixed-use development led to sprawling cities with destinations spread far apart, connected by high-speed roadways.

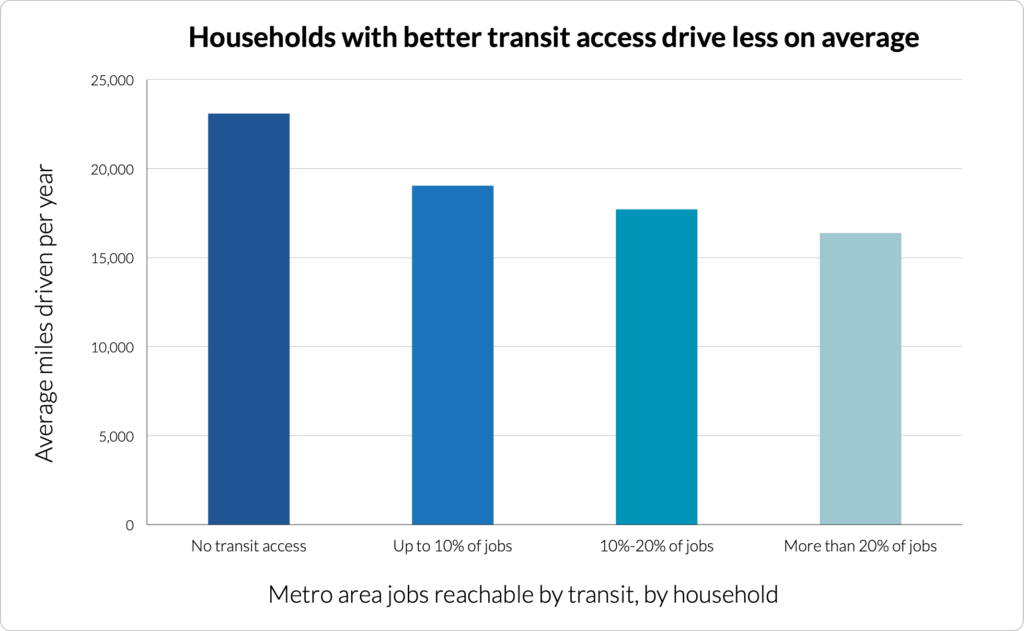

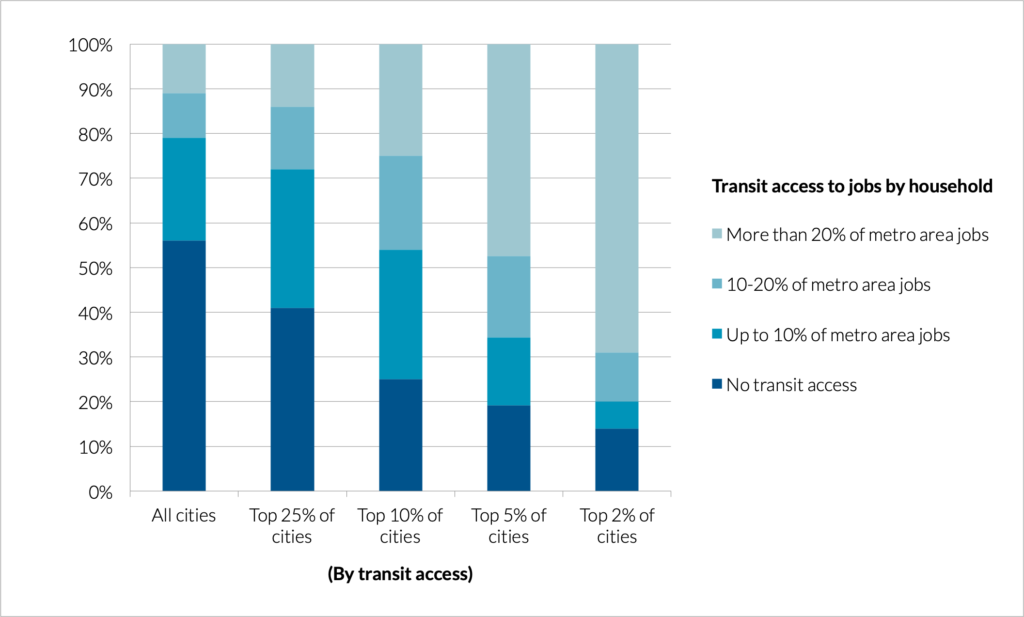

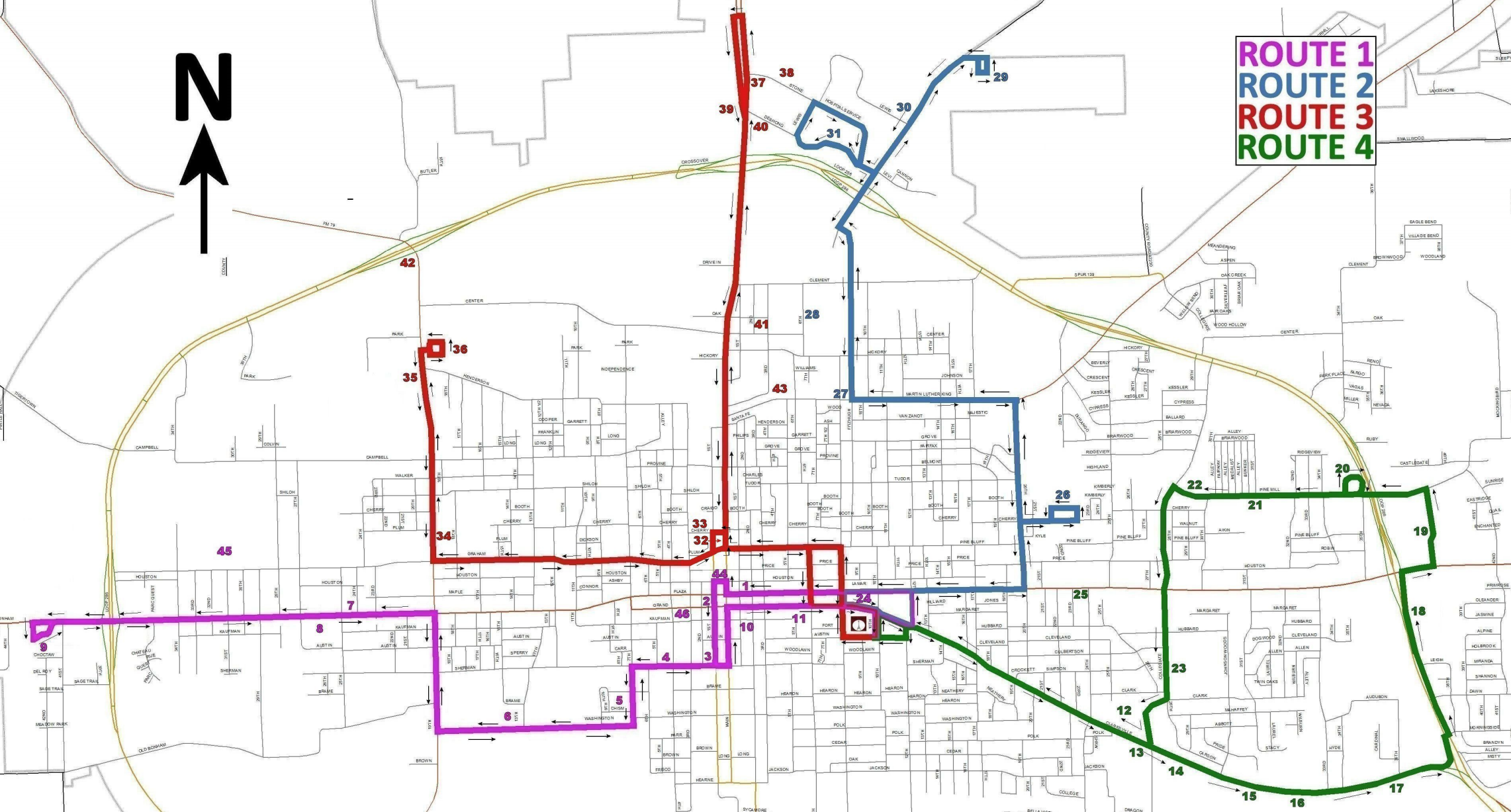

Today, Americans are driving more for the same basic tasks. Research from Transportation for America and Third Way found that households in both rural and urban areas are driving significantly farther per trip as of 2017 than they were in 2001 to accomplish their commutes and daily tasks. Often, driving is the only convenient, safe, and reliable transportation option available, requiring households to shoulder the cost of a vehicle in order to access their daily needs. When people can’t afford regular access to a vehicle, when their car breaks down, or when they otherwise don’t have the ability to drive, they must navigate a transportation system that wasn’t built for them.

A lack of safe transportation options leads to reduced access to economic opportunity, increased risk of being hit by a vehicle, and higher rates of air pollution. These trends are felt by everyone, but they have the harshest impact on low-income communities and communities of color.

Reminder that we destroyed our own cities.

— Culture Critic (@Culture_Crit) September 1, 2023

(Main & Delaware Street, Kansas City) pic.twitter.com/2SojGFDPbp

We need Complete Streets

Decisions made in the past have left our streets incomplete, prioritizing one way of travel over a wealth of other options. Complete Streets are streets that are safe for all users and that connect community members to the resources they need. This blog is the first installation of a four-part series on the Complete Streets movement. Keep an eye out for our next blog, where we’ll dissect the origins of the Complete Streets movement and what it aims to achieve.