In the United States, where and how traffic deaths occur are painfully predictable. But even with historically high levels of funding available, traffic engineering standards and federal policy combine to create a safety catch-22, ensuring that a transportation agency walking the walk on traffic safety is the exception, not the rule.

If you’re somebody who walks or rolls to get to work, school, or any of your other daily needs, chances are that you know the most dangerous parts of your local transportation system: the crosswalk that cars don’t stop at because there’s no light, the bike lane that ends abruptly, or the sidewalk ramp pointed to the middle of an intersection instead of the crosswalk. When you go through these areas, you might think that they’re oversights, mistakes made by an inattentive traffic engineer or planner who would make the adjustment needed if they just walked or rolled a mile in your shoes. But in reality, these flaws are part and parcel of a broader system that requires either reckless behavior or deaths to make the case for safety.

Instead of proactively asserting a right for people to walk and roll safely and conveniently outside of a vehicle, the standards that DOTs use to determine when and where they put safety infrastructure actually require people to either risk their bodies or experience harm before any paint or concrete are poured.

Transportation for America is a program of Smart Growth America, an organization that empowers communities through technical assistance, advocacy, and thought leadership to realize our vision of livable places, healthy people, and shared prosperity. See how Smart Growth America is engaging with National Pedestrian Safety Month here.

The safety infrastructure catch-22

One hot summer morning in 2021, I went to an unsignalized intersection in Northern Virginia and watched people wait for a break in traffic to cross a road that was 60-feet wide, dividing homes and a bus stop from a food bank. Though state law makes it legal for people to cross on foot at unsignalized intersections, it’s obviously a risky, unsafe thing to do.

But this is the catch-22: For the state DOT (VDOT) to paint a crosswalk there, they require that at least 20 people choose to cross that dangerous street each hour.1 Put another way, if enough people engage in risky, unsafe behaviors, the state might decide to make it safer. But when it’s unsafe to walk and roll, fewer people are going to do so. And with fewer people walking and rolling, DOTs like VDOT think that there’s little demand for safe infrastructure.

This unproductive cycle is the product of street design standards and manuals that your local traffic engineer relies on and navigates in order to make their decisions. In some cases, as NACTO says about the Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), it can actually “require multiple people to die at an intersection before a pedestrian signal is ‘warranted’.”

Why did the pedestrian cross the road?

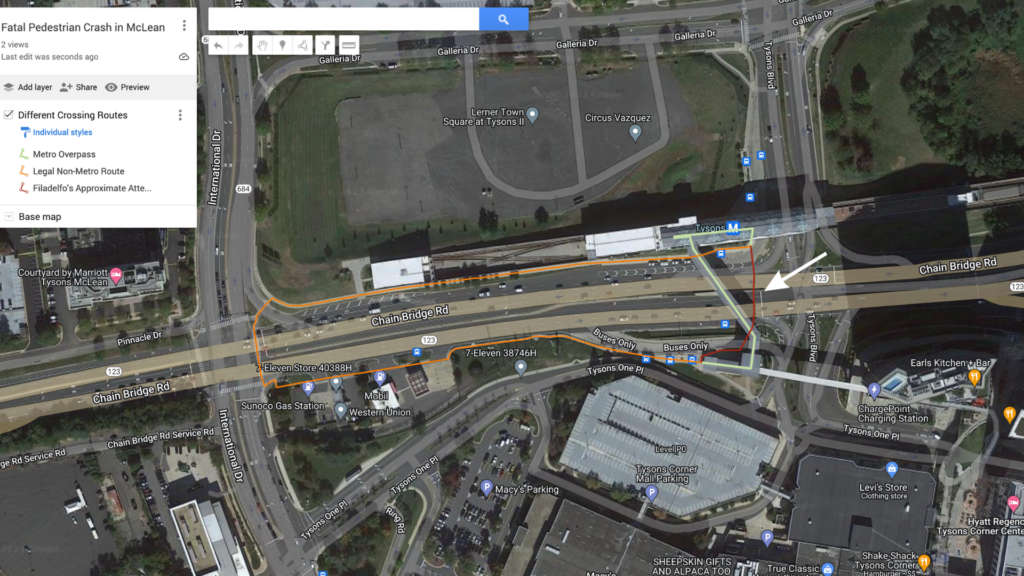

The people who pay the price for this nonsense approach to safety are people like Filadelfo Ramos Marquez. Filadelfo was killed in December 2021 while crossing an eight-lane road in Tysons Corner, Virginia. Those responsible for the street’s design can choose to blame the victim for not using a crosswalk as a way of abdicating their responsibility, or they can ask: why did he cross where he did, and how do we make it safer?

Although this intersection has traffic lights, the only way to cross it on foot is via a pedestrian bridge. However, when the metro station that the bridge connects to closes, so does the bridge itself. If Filadelfo thought that the station was already closed at 9 p.m., or that he had to pay a metro fare in order to use the bridge, then he had two choices: cross where he did, or add a third of a mile to his trip in order to use a painted crosswalk.

This leads us to the broader point: We do not currently measure OR care about the travel time of people who walk and roll. Pedestrians’ time isn’t just worth less than that of drivers, it’s not measured at all. In VDOT’s standards for an unmarked crosswalk at an unsignalized intersection, like the one I went to in summer 2021, the agency effectively says (starting on page A4) that saving pedestrians time is fine, so long as it doesn’t affect too many drivers.

The intersection where Filadelfo was hit, with signals for cars but no accommodations at all for pedestrians, illustrates this biased tradeoff just the same. When this metro station was built, planners and engineers could’ve viewed it as an opportunity to improve the pedestrian experience, both around this one stop and along this entire corridor where crosswalks are routinely over 130 feet long. Seeing as Tysons Corner has two huge shopping malls, is one of the largest job centers in Virginia, and aims to be home to 100,000 residents by 2050, some might say this would’ve been prudent. But that would have required deprioritizing the 46,000 vehicles per day that drove here pre-pandemic. So instead of building the much shorter, much less expensive straight-line street-level crossing, they built the longer, more expensive pedestrian bridge. And now, instead of asking why pedestrians like Filadelfo still choose to cross roads like this, DOTs like VDOT simply pray they don’t.

Potential pedestrian routes in the area where Filadelfo was hit and killed. The green line shows the path using the pedestrian bridge that connects to the metro station. The orange line shows the route to the only marked crosswalk nearby. The red line and white arrow show Filadelfo’s route and the general area where he was hit.

The safety funding catch-22

One reason agencies seem to prefer the thoughts and prayers approach to traffic safety is that federal policy encourages them to. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) poured over $400 billion into roads and streets across the United States, but with few requirements for anyone to measurably improve safety. Although all of that money could be used to ensure the safety of all road users, most of it won’t be.

Instead, in exchange for billions in largely flexible formula grants they control, states are required to set safety performance targets each year. But the reality is almost laughable: states can literally set targets for more people to die without penalty, and there is almost no penalty for failing to meet even the most unambitious targets. Failing to meet targets just requires those states to spend their Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP) dollars on highway safety improvement projects. And if vulnerable road users (VRUs) make up more than fifteen percent of all fatalities in a state, that state has to spend fifteen percent of their HSIP funds the next year on safety projects for VRUs. (However, most states aren’t even obligating all the safety funds they need to.)

In contrast, if local governments want to access funds specifically earmarked for safety, they usually have to spend time and money applying for competitive discretionary grants, like the Safe Streets and Roads for All program. Although this is better than nothing, and there’s additional marginal progress being made, the IIJA has the same double standard for safety that it does for climate: projects that improve safety are the exception, whereas projects that don’t are the rule.

And so long as making streets safer comes with tangible costs but traffic deaths do not, people will pay with their lives. The day before Filadelfo was struck, Matthew Jaeger was killed while riding a bike a few miles down that very same road.

To get to the other side

Changes need to come from the top down and the bottom up. Congress needs to stop creating small new programs for improving safety. After giving them billions to spend, Congress should hold states accountable for reducing fatalities. For states that fail to do so, this could mean requiring them to transfer money out of block grant programs (like the the National Highway Performance Program and Surface Transportation Block Grants) and move it to HSIP for every year that they don’t meet their targets.

USDOT can finish updating the MUTCD and improving the Green Book. In the meantime, if states can prove these documents interfere with achieving safety targets due to their erroneous assumption that speed is safety, USDOT should waive these design standards. The agency can also ensure regulations like the New Car Assessment Program look at how the weight, size, visibility, and marketing of vehicles keeps all road users safe.

States control the most dangerous streets, and they stay dangerous because states continue to prioritize speed and vehicle throughput over safety—as with the corridor that killed Matthew and Filadelfo. States actually addressing this danger would see immediate results in pedestrian safety.

And while cities press their states for action on the deadly state-owned arterial roads within their borders, they are free to make the streets they do control safer. They can pass Complete Streets policies, discarding their state’s speed-first design guidelines, and adopt modern street design guidance that prioritizes moving people and creating safe streets for everyone. (The IIJA made a vital change to allow cities to adopt NACTO’s Urban Street Design Guide, even if their state prohibits it.)

Anything less than these changes isn’t prioritizing safety. It’s just a catch-22.

Find more recommendations to make our roadways safer in Dangerous by Design.