Beth Osborne

Performance measures should be used to prioritize and account for public spending and, through this, demonstrate to the public that their dollars are being used wisely. There are four ways to deploy performance measures: 1) create a dashboard, 2) prioritize projects, 3) optimize investments and 4) check on the performance of past investments.

This is the fourth post in a series on performance measures by Beth Osborne, T4America Senior Policy Advisor. Catch up on the series with a high-level overview of the concept, find out how and why you should go beyond the federal requirements and learn more about choosing the best measures for addressing your priorities. -Ed.

A dashboard

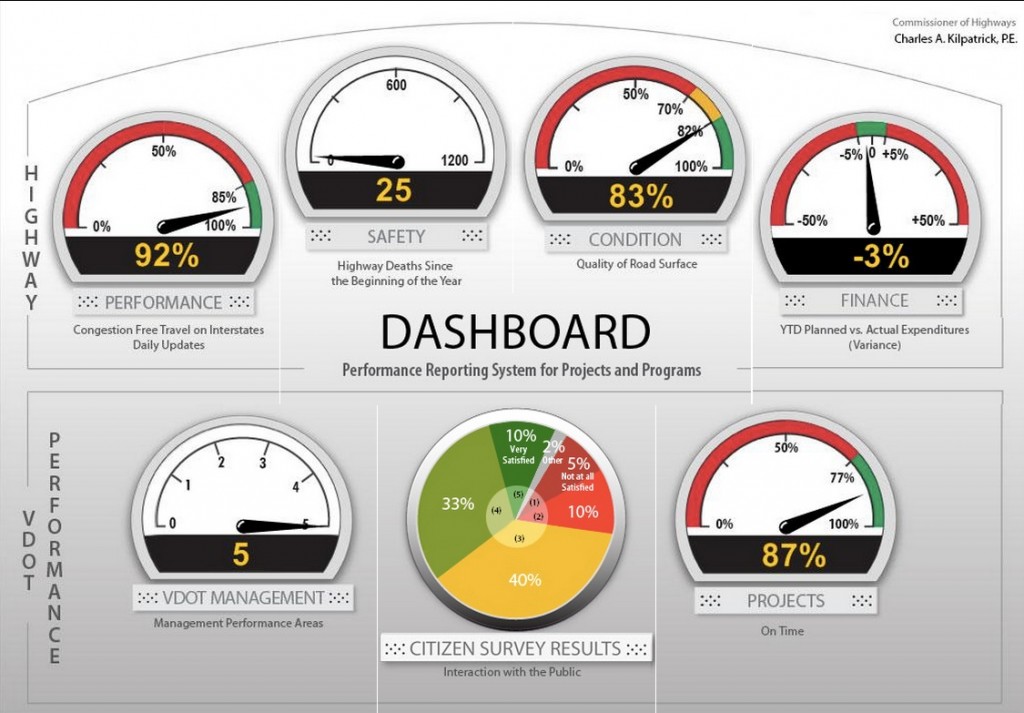

A visualization of data or metrics known as a “dashboard” can be a useful snapshot of current conditions or the direction an area is moving. Dashboards are useful because they are visual and quickly lay out in one glance the region’s goals and the current status. Two examples are Salt Lake City and the Virginia Department of Transportation.

The development of a dashboard can help determine what the public wants to prioritize — the public has an easy-to-digest summary of core statistics about your transportation network to help them choose what’s important. But this tool has a notable limitation: it’s not responsive to those public priorities if it isn’t also connected to decisions about public spending. After all, you could have an elegant dashboard that’s easy for anyone to understand rating the safety of the roadway…while making no investments in roadway safety.

A dashboard doesn’t automatically make it clear that any investment decisions are being made to impact the statistics being measured or displayed.

Prioritizing projects

The State of Virginia recently decided to take steps to ensure that the public’s priorities were better reflected in their process of selecting projects. Their legislature passed a bill in 2014 requiring all new capacity projects to be weighed against each other based on five priority areas: congestion reduction, economic competitiveness, access to opportunity, safety and environmental protection. They created a process — now available to the public —for ranking these outcomes based on significant public input.

Optimize investments

Spurred on in part by funding uncertainty, The State of Tennessee took a step back and analyzed their entire list of planned projects with a critical eye. They looked closely at the expected outcomes of their planned projects and then searched for other less expensive ways to accomplish the same things. The results were quite impressive, with multi-million dollar projects replaced by projects that cost just hundreds of thousands, saving millions and still bringing 80-90 percent of the benefits of the more expensive project. (A presentation on their new process can be found here.)

How have past investments performed?

In the world of transportation planning where everyone is always looking forward, forward, forward, it can be incredibly useful to take a look backwards on a regular basis and see if past choices have met projections and brought the benefits promised — and recalibrate the process if they have not.

Transportation agencies do their best to project the outcomes of each investment, but no one can get it right all the time. The agencies that are making the most of their dollars are the ones that check back on their investments to see if they performed as expected and, if they did not, make changes.

To do this, the goals of each project must be clearly stated and then reviewed at major milestones to see if the expected results materialized. The public notices when we make promises that don’t come true, and being right there with them and explaining what will change with the process is an important way to build credibility. We must check our own work and continually improve our performance, especially if we want the public to continue to invest in our programs.