On the surface, President Trump’s FY26 “skinny budget” framework, released on Friday, May 2, 2025, suggests limited implications for the nation’s transportation funding. However, a closer look reveals that the budget, if implemented, stands to have outsized funding impacts on programs tied to Complete Streets, active transportation, transit, transportation electrification, and capacity building.

The FY26 budget season is kicking off in earnest on Capitol Hill, amid the ongoing budget reconciliation process. As part of the process, the Trump administration has a chance to lay out its priorities to Congress on how it should deliver on the federal government’s national role. Congress will debate and adjust that budget framework before it is voted on and ultimately signed into law.

On May 2, 2025, the Office of Management and Budget presented a FY26 “skinny budget” framework to Congress, outlining investment priorities for the next fiscal year. The budget request has drawn headlines as it proposes to cut $163 billion in programs, including those that would slash vital housing and community development programs, with the remaining allocated domestic funding further reorganized to advance the administration’s domestic priorities.

On May 2, 2025, the Office of Management and Budget presented a FY26 “skinny budget” framework to Congress, outlining investment priorities for the next fiscal year. The budget request has drawn headlines as it proposes to cut $163 billion in programs, including those that would slash vital housing and community development programs, with the remaining allocated domestic funding further reorganized to advance the administration’s domestic priorities.

On the surface of the budget framework, transportation spending remained relatively unchanged, allocating nearly $1.2 billion more than the existing IIJA allocation for INFRA, rail safety, and rail infrastructure grants. But digging into the framework and its impact on the transportation system, the administration’s recommendation would entrench car culture and delegate transportation strategies to the states. The framework explicitly calls for over $300 million in cuts to essential air service, which serves rural communities. Whatever the reason for these cuts, without enhancing passenger rail service and infrastructure investments in parallel, these rural communities stand to lose connection to vital access to jobs, services, and health care.

However, our concerns for the transportation program come more from what is not spelled out in the President’s recommendation. Not all programs in IIJA have guaranteed funding from the Highway Trust Fund, meaning they rely on annual federal appropriations. These programs include grants for passenger rail, transit, Complete Streets, and other multimodal transportation initiatives. The lack of reference to these transportation programs in the budget framework seems to strongly suggest that these programs are not priorities for the administration. The administration’s budget framework also would rescind $4.1 billion in IIJA advanced appropriations. The budget framework provided little clarity as to which targeted advanced appropriations would be cut, nor which timeframe (whether just FY26 or clawing back past years’ funding), but fact sheets from the administration indicate much of it could come from the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure program.

The budget framework also goes after capacity building, technical assistance, and infrastructure funding to advance Complete Streets and active communities. The CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion is proposed to be eliminated, as part of $3.6 billion in cuts from the Department of Health and Human Services. The Center provides critical support to lower-capacity communities to advocate for and build Complete Streets, while encouraging thriving active communities. The administration argues that the states and localities should be responsible for their own capacity building and investments for Complete Streets. That isn’t always possible, often due to a lack of local/state resources to recruit and maintain adequate capacity to plan, design, and build Complete Streets. For many communities across the nation, the mayor and a few key staff may be juggling multiple municipal roles to keep essential services running.

Lastly, the budget framework further targets investments and tax credits that support the growth and transition to electric vehicles, cutting more than $15 billion in IIJA funding from the Department of Energy. Within this cut, there is overlapping funding with USDOT that advances EV infrastructure and EV manufacturing capacity in the U.S.

What’s next?

President Trump’s budget proposal is an opening conversation from the administration to Congress, and will likely create debates on national investment priorities. Transportation advocates should keep an eye out for the next step in the process, with the administration anticipated to deliver a detailed FY26 budget proposal to Congress by the end of May. That’s when the details of the budget framework will reveal which programs are recommended to be cut and the associated program policy changes that the administration will work to advance. Given the massive cuts to important programs, Congress will likely face heated debates over what the final FY26 budget will look like—if it doesn’t default to another continuing resolution as we‘ve seen in past budget cycles.

Now is the time to reach out to your elected representative and tell them how these changes would impact you. To make a strong case, advocates should gather and share stories and local data illustrating how the cuts would affect safety, access to jobs, and economic opportunity. As Congress begins shaping the final FY26 budget, local perspectives will be essential to protecting the programs that communities rely on.due

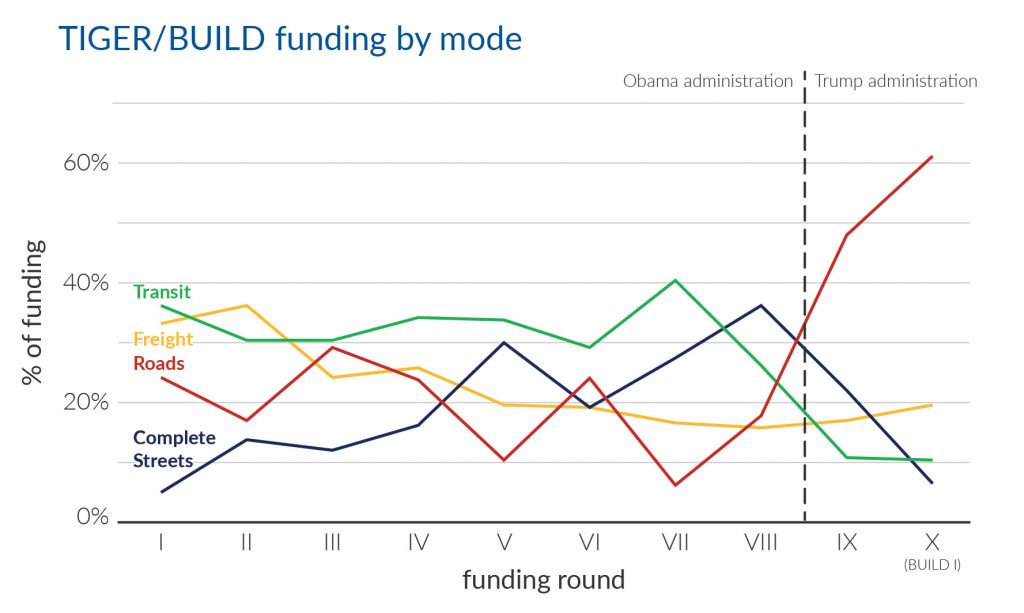

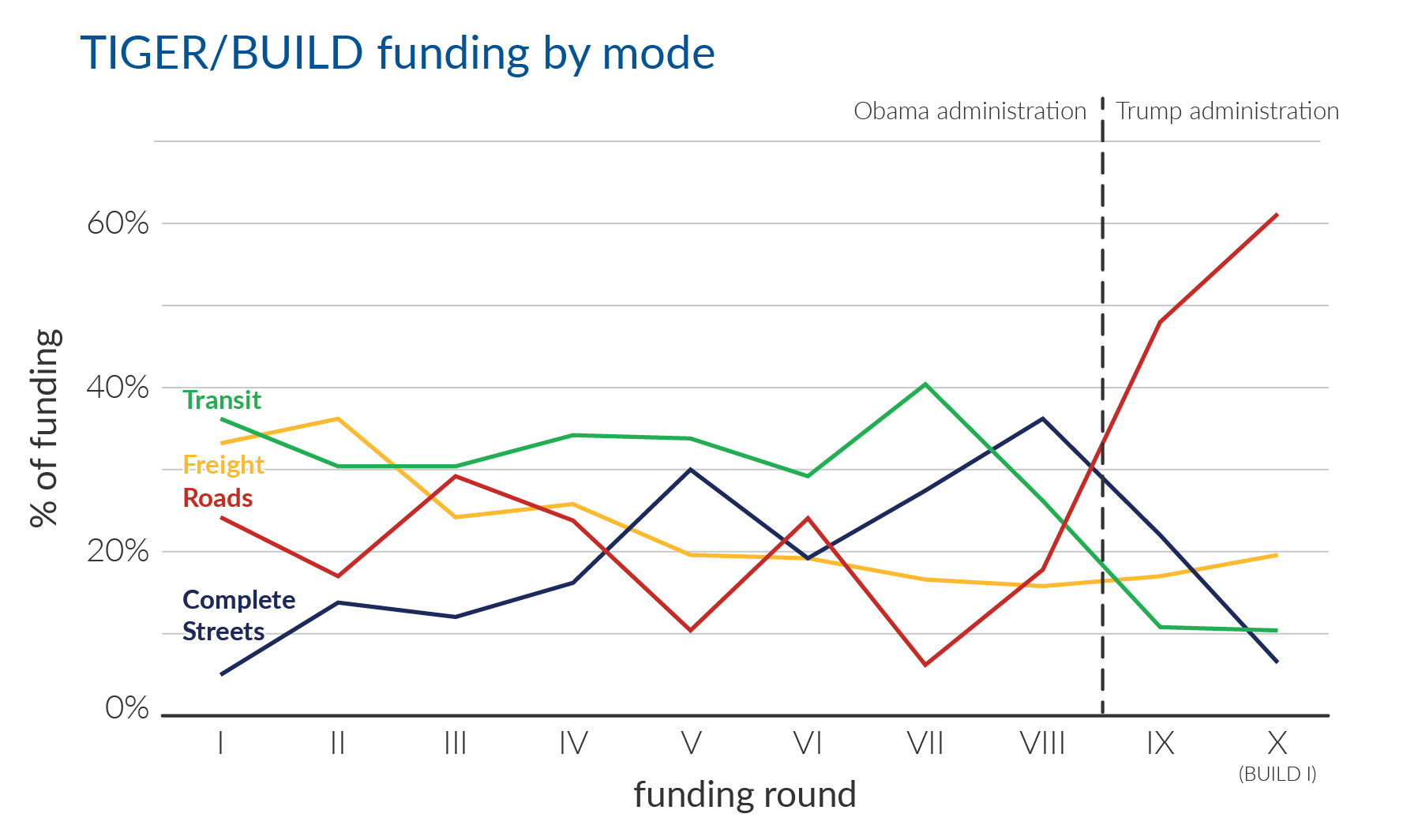

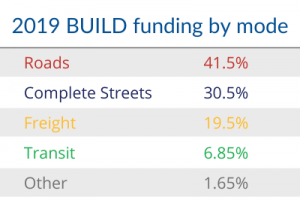

But there is a bit of a silver lining: Complete Streets & other multimodal projects racked up almost a third of the BUILD funding, the highest percentage such projects have received under the Trump administration. This is also particularly notable given the worrying rise in pedestrian and bicycle fatalities across the country, attributable in large part to the lack of safe infrastructure on our roadways for people without cars.

But there is a bit of a silver lining: Complete Streets & other multimodal projects racked up almost a third of the BUILD funding, the highest percentage such projects have received under the Trump administration. This is also particularly notable given the worrying rise in pedestrian and bicycle fatalities across the country, attributable in large part to the lack of safe infrastructure on our roadways for people without cars.

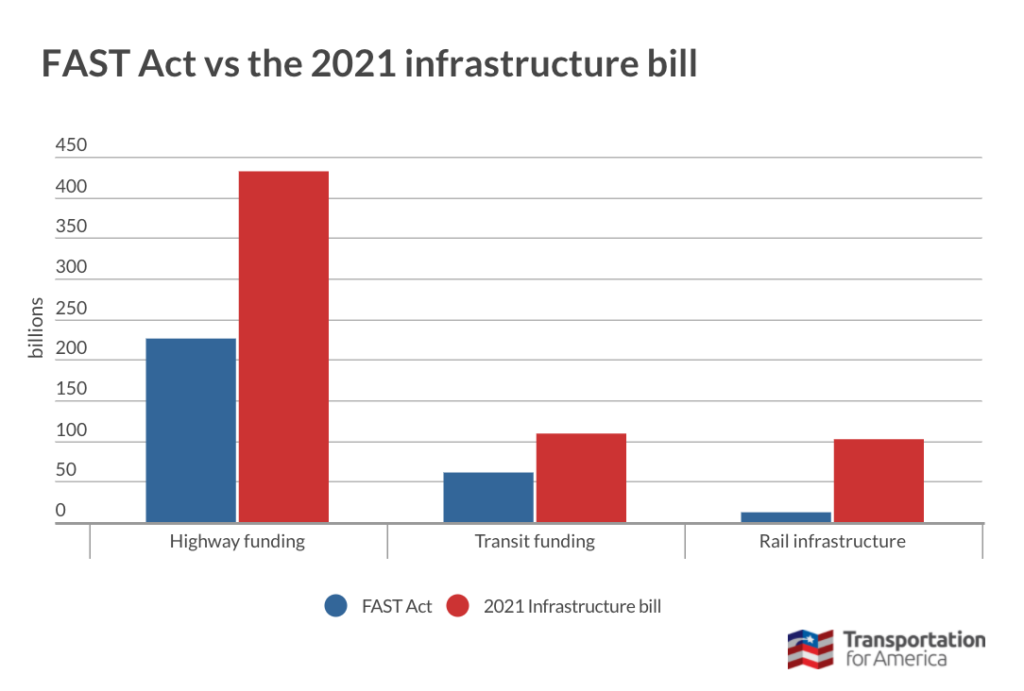

Rep. Garcia echoed this sentiment, saying, “It boils down to social justice. People cannot afford to get to where they need to go or stay where they grew up. We need to take a step back and start thinking about what it is we’re throwing hundreds of billions of dollars [at] every year.”

Rep. Garcia echoed this sentiment, saying, “It boils down to social justice. People cannot afford to get to where they need to go or stay where they grew up. We need to take a step back and start thinking about what it is we’re throwing hundreds of billions of dollars [at] every year.”