As a valued member, Transportation for America is dedicated to providing you pertinent information. This includes policy updates and summaries to inform your work. Check out the latest on Automated Vehicles and TIGER Notice of Funding Opportunity.

Senate Bill on Automated Vehicles

On Friday, September 8th the Senate Commerce Committee Chairman John Thune (R-SD) and Sen. Gary Peters (D-MI) released draft legislation to set new federal regulations for automated vehicles (AVs). The bill would set nationwide policy for AVs and preempt state and local requirements; significantly expand the number of test vehicles allowed on the roads; and limit data sharing requirements. AV manufacturers and operators have advocated for a single, national set of rules. T4America and our partners are concerned that this bill cuts out local governments and undermines safety in our communities. T4America has been working with the Senate to ensure local governments preserve their authority to control their roadways, and improve data collection and sharing about autonomous vehicles.

A detailed summary of the draft bill is included below.

Background

On Friday, September 8, the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee released a draft of their automated vehicle legislation. Commerce Committee Chairman John Thune (R-SD) and Sen. Gary Peters (D-MI) have been leading the legislative efforts on automated vehicles in the Senate.

T4America expects the sponsors to release an updated bill draft this week. This revision may address some of the concerns raised by stakeholders, including T4America. The Commerce Committee is expected to markup the revised bill next week.

The release of the Senate discussion draft follows action in the House of Representatives, which on Wednesday, September 7 passed by voice vote their bipartisan automated vehicle legislation, H.R. 3388, the SELF DRIVE Act.

The impetus for both bills comes from a desire from manufacturers and operators of automated vehicles to move away from the current patchwork of state rules and regulations over testing and deployment of automated vehicles, and instead establish a relatively uniform standard at the federal level.

What T4America is Doing

T4America is working with the 16 cities in our Smart City Collaborative (SCC) and a number of partners including the National Association of Transportation Officials (NACTO), the National League of Cities (NLC), and New York City to give feedback to the Senate Commerce Committee on the concerns we have about the discussion draft, and push our proposed legislative language changes. We met with both majority and minority Committee staff on Friday and the Committee seemed receptive to some of our concerns around preemption and data sharing.

Additionally, we have met with staff for numerous Senators on the Commerce Committee about the discussion draft, including staff from Senators Nelson (D-FL), Baldwin (D-WI), Peters (D-MI), Cantwell (D-WA), Duckworth (D-IL), Klobuchar (D-MN), Markey (D-MA), Blumenthal (D-CT), Cortez Masto (D-NV), Inhofe (R-OK), Ron Johnson (R-WI) and Blunt (R-MO).

What is in the bill

The Senate discussion draft does a number of things including:

- Delineating the federal and state/local roles when it comes to regulating automated vehicles via a pre-emption clause;

- Establishing a specific exemption from federal motor vehicle safety standards to test automated vehicles;

- Raising the number of safety exemptions a manufacturer can get to test vehicles to 100,000 over three years; and

- Establishing an automated vehicle advisory committee to advise the Secretary of U.S. DOT on a number of issues related to automated vehicles.

Preemption

The Senate draft preempts any state or local government from passing a new, or enforcing an existing, law or regulation in any of the nine categories of data that manufacturers are required to submit to the Secretary of Transportation as part of the Safety Evaluation Report required in section 9 of the draft. The nine areas preempted in the draft bill are:

- How the AV avoids safety risks, including whether its safety systems are functioning properly;

- Data collection of an AV’s performance, including its crashes and disengagements;

- Cybersecurity;

- Human-machine interface;

- Crashworthiness;

- Capabilities of the automated vehicle;

- Post-crash behavior;

- Compliance with traffic laws and rules of the road; and

- The behavior and operation of the AV during on- or off-road testing, including an AV’s crash avoidance capability.

The stated intent is to apply the existing federal-state preemption framework, which mainly deals with the design, construction and performance of vehicles, to automated vehicles. However, as written the preemption language seems to be broader than the existing framework because it would preempt any state or local law and regulation related to the areas listed above, rather than just laws dealing with the design, construction or performance of automated vehicles in those areas.

Safety Evaluation Report

The Senate discussion draft requires that manufacturers must submit a Safety Evaluation Report (SER) to the U.S. DOT Secretary in order to receive the exemption to test AVs. The bill specifies that the manufacturer’s SER should provide a description of how the automated vehicle would address the same nine areas mentioned above.

The discussion draft also requires the Secretary to make this data publicly available. However, the draft requires the Secretary to redact the data considered to be a trade secret or confidential business information The bill prohibits the Secretary from conditioning pre-approval of the testing, deployment, or sale of automated vehicles to consumers on a review or approval of the Safety Evaluation Report submitted by manufacturers.

Data Sharing

Other than the SER that operators must submit to U.S. DOT, the discussion draft includes no requirements that operators or manufacturers of automated vehicles share any data with the states, localities, or law enforcement organizations in the places they are testing or deploying automated vehicles.

Automated vehicle technology has the potential to provide aggregated information about how people and goods move through our streets, but without access to these data, city and state governments will be blind to the impacts of emerging transportation technologies.

Data on vehicle collisions and near-misses allows cities to proactively redesign dangerous intersections and corridors to ensure safety for all street users. Understanding vehicle movement at the corridor level provides immense value for governments and citizens. Real-time data on vehicle speeds, travel times and volumes has the potential to inform speed limits, manage congestion, uncover patterns of excessive speeds, evaluate the success of street redesign projects and ultimately improve productivity and quality of life.

Because of the importance of real-time data, T4America and our partners are urging the Committee to include data sharing requirements which protects the privacy of users and legitimate trade secrets while providing states, municipalities and law enforcement the real time data necessary to ensure the safety of AVs in their communities. Such data would potentially cover areas like the number of crashes and disengagements an AV has had, the types of roads AVs have had problems on and the weather conditions at the time of a crash or disengagement.

Level of Exemptions

The bill would allow manufacturers to apply for an exemption from federal motor vehicle safety rules to test automated vehicles. Over a period of three years, the Senate draft would raise the cap on exemptions per manufacturer for testing automated vehicles forty-fold, from 2,500 to 100,000. There are potentially up to 20 manufacturers interested in testing automated vehicles, so if each manufacturer maximizes the 100,000 exemptions allowed, that could be up to 2 million automated vehicles testing on the road. There are no restrictions in the bill on where automated vehicles could test or restrictions on how many automated vehicles could be tested in a given area. Theoretically, a manufacturer could test all 100,000 vehicles in one city or state.

Automated Vehicle Advisory Committee

The Senate discussion draft proposes a new “Highly Automated Vehicles Technical Safety Committee” to advise the U.S. DOT Secretary on a host of issues related to the safety of automated vehicles. The discussion draft specifies that the Secretary shall select 12 members of the Committee drawing from industry, safety advocates, or state and local government representatives. The bill does not specify committee memberships for specific groups, however. Theoretically, the Secretary could appoint all 12 members from industry and zero from state and local governments or vice versa.

Commercial Vehicles

One issue totally left out of the Senate discussion draft is whether commercial vehicles (defined as motor vehicles over 10,000 pounds) should be included in this bill, which is a controversial topic. The Senate Commerce Committee held a hearing this past Wednesday specifically to examine whether commercial vehicles should be included in the bill. A number of witnesses, including the American Trucking Association, urged the Committee to include commercial vehicles, so that remains a possibility as the legislative process in the Senate moves forward. From our understanding, Chairman John Thune (R-SD) would like the legislation to include trucks while Democrats, including Senator Gary Peters (D-MI) are vehemently opposed to including automated trucks in this draft. If trucks are included in the draft, staff from Democratic offices have indicated that any chance of bipartisan support for the bill would go away.

Conclusion

There is tremendous interest in Congress in speeding up the testing and deployment of automated vehicles because of the concerns of industry that the U.S. is falling behind other countries because of a lack of a national regulatory framework for AVs. Additionally, Congress is excited about the life-saving and revolutionary benefits AVs can bring in terms of motor vehicle safety and expanding mobility options for the people with disabilities, seniors, and other groups that may not drive or have access to a car. Therefore, legislation in some form around AVs is likely to become law. Right now, Congress is trying to strike the right balance between deploying these AVs as fast as possible while making sure they are tested and deployed in the short term in a safe manner that doesn’t endanger the safety of other persons because of the problems and unforeseen issues that arise when testing a new technology.

TIGER Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO)

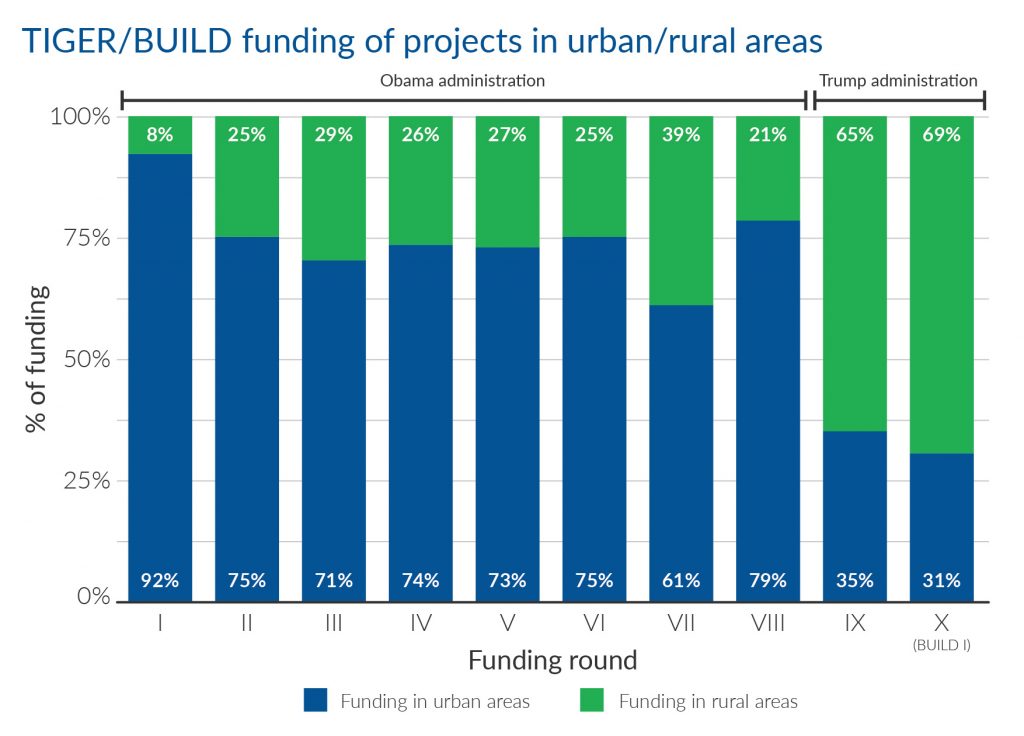

As a reminder, U.S. DOT recently released the FY 2017 notice of funding opportunity (NOFO) for the $500 million TIGER program. U.S. DOT will evaluate projects based on the extent to which they benefit safety, economic competitiveness, state of repair, quality of life and environmental sustainability. These are the same selection criteria used in the TIGER rounds from 2014, 2015, and 2016. However, this Administration will emphasize “improved access to reliable, safe, and affordable transportation for communities in rural areas, such as projects that improve infrastructure condition, address public health and safety, promote regional connectivity, or facilitate economic growth or competitiveness.”

Applications are due by 8:00 p.m. E.D.T. on October 16, 2017 through the grants.gov portal. U.S. DOT hosted informational webinars on Wednesday September 13th, Tuesday September 18th, and Wednesday September 19th. You can find recordings and information related to the webinars from U.S. DOT here.

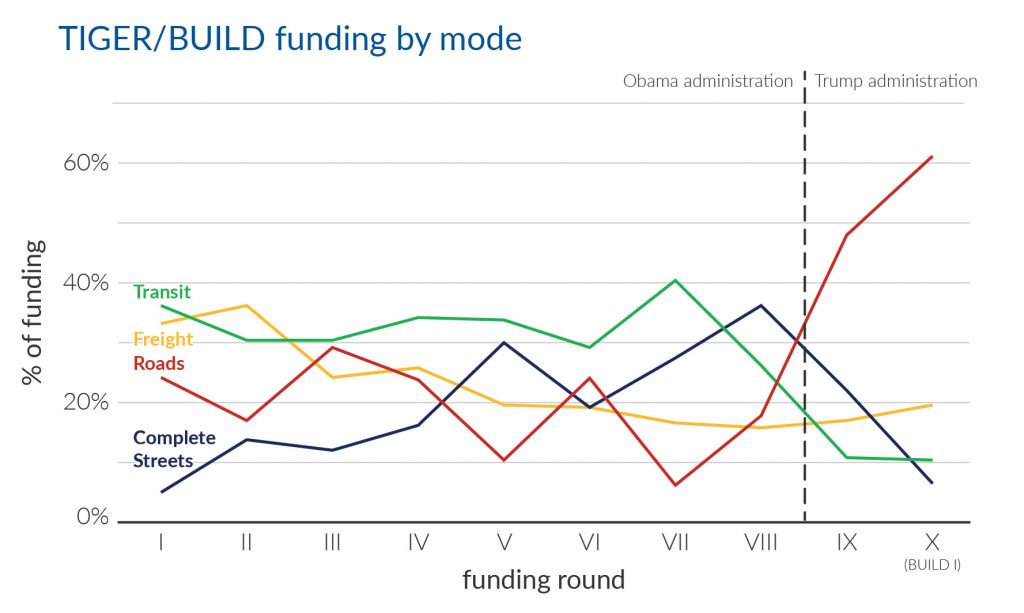

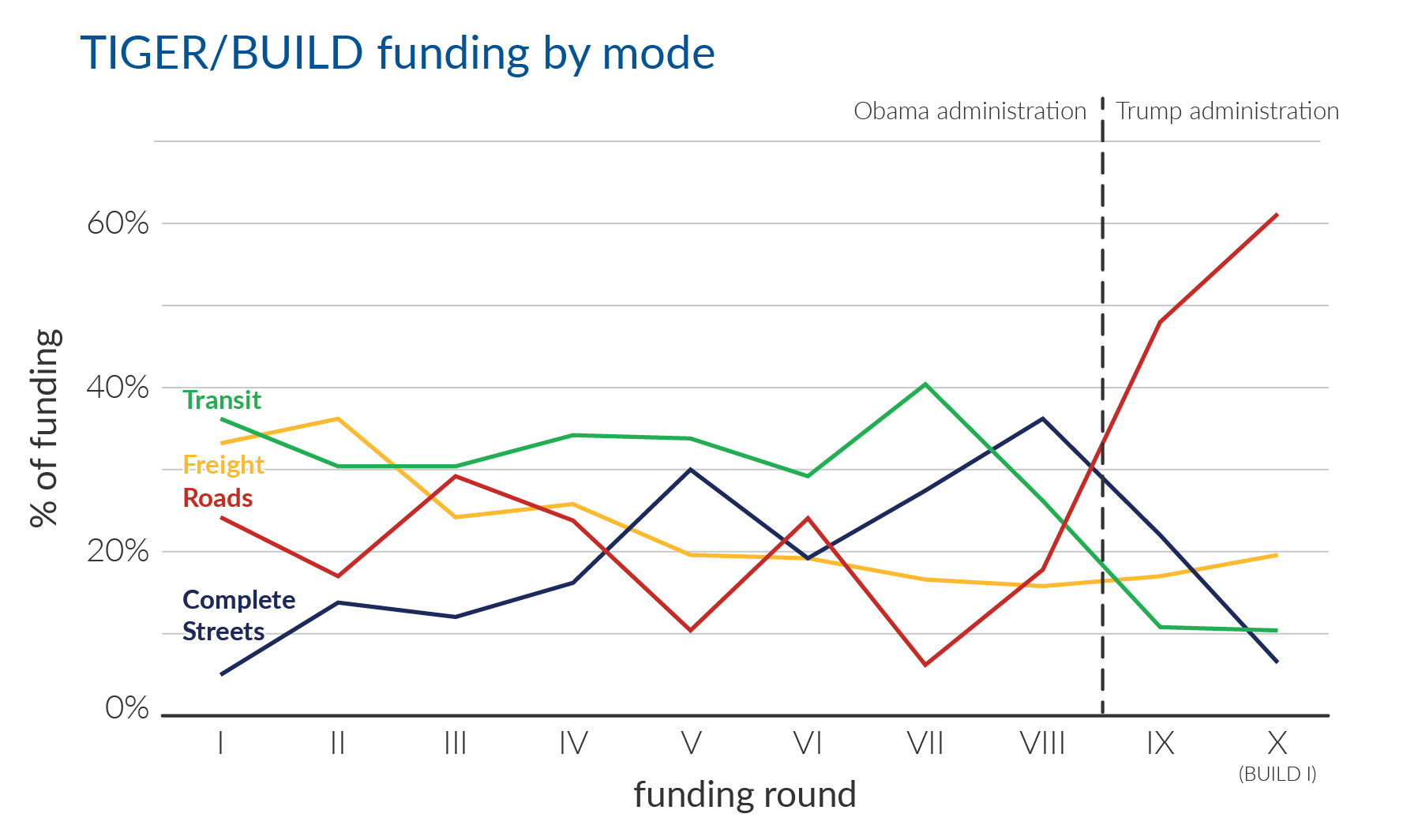

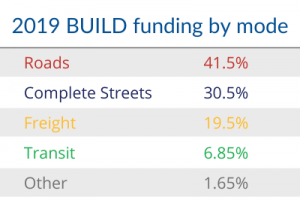

But there is a bit of a silver lining: Complete Streets & other multimodal projects racked up almost a third of the BUILD funding, the highest percentage such projects have received under the Trump administration. This is also particularly notable given the worrying rise in pedestrian and bicycle fatalities across the country, attributable in large part to the lack of safe infrastructure on our roadways for people without cars.

But there is a bit of a silver lining: Complete Streets & other multimodal projects racked up almost a third of the BUILD funding, the highest percentage such projects have received under the Trump administration. This is also particularly notable given the worrying rise in pedestrian and bicycle fatalities across the country, attributable in large part to the lack of safe infrastructure on our roadways for people without cars.