Our roads have never been deadlier for people walking, biking, and rolling and the federal government and state DOTs are not doing enough. If we want to fix this, we have to acknowledge the fact that our roads are dangerous and finally make safety a real priority for road design, not just a sound bite.

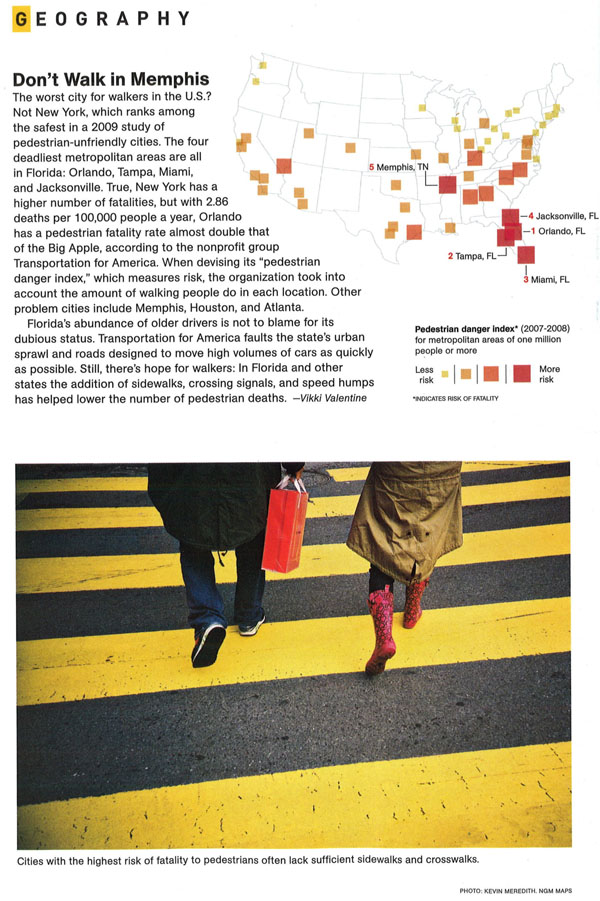

Transportation in this country is fundamentally broken, creating a dangerous environment for everyone who uses it but especially for those outside of vehicles. The way we’ve built our roadways has transformed what should be easy trips into potentially deadly journeys. Though our cars have more safety features than ever—cameras, lane keep assist, automatic braking—those advancements have only served to protect people within vehicles. They didn’t save any of the 7,522 people killed while walking in 2022. In fact, as cars become safer for people inside the vehicle, they have gotten even larger and more deadly for people outside of them.

The fact of the matter is that fast-moving vehicles present a danger to people walking. We can’t address this danger if we are unwilling to commit to safer speeds.

We can’t do it all

The policies and practices that inform the design of our roadways often serve one primary goal: to move as many cars as possible, as quickly as possible. That negates the experience of everyone walking, biking, and rolling. Yet, if you asked the same people designing our roadways and dictating these policies whether safety is their top priority, they would absolutely say yes. Our approach to road design, reinforced by federal guidance and manuals, continually tries to juggle both speed and safety, when these two goals are fundamentally opposed.

When we try to prioritize both safety and speed, drivers end up receiving competing messages. Current roadway design requires people to drive perfectly while creating an environment that incentivizes risky behavior such as speeding. Safe roadways don’t ask people to slow down. They are designed so that safe speeds are the most intuitive option.

Less talk, more action

USDOT and other agencies have called for safer streets, but federal funding and policies haven’t led to results. This can be attributed to a variety of factors, including the relatively small amount of money set aside to specifically address safety compared to the much larger amount of money going to build even more dangerous roads.

State departments of transportation are allowed to set safety goals where more people die every year, knowing they will get more funding regardless. Meaningless “safety” targets allow governments to point their fingers and say they’re working on it while building even more deadly roads. The danger is often not addressed until multiple people get hurt. It’s no surprise that the majority of pedestrian deaths occur on federally funded, high-speed state roads.

There are not enough policies to support environments where safe mobility is available for all modes. The Surgeon General called to promote walking and walkable communities and to create a built environment that allows for human connection. The USDOT’s supposed top priority is safety and the Federal Highway Administration has a long-term goal of zero roadway deaths. But there’s no follow through on these statements. We want people to go on walks, and kids to play outside, and for there to be less deaths on the road, but our policies and tax dollars continue to primarily support projects that overlook non-vehicular traffic—at the expense of everyone else. Our transportation system is built on a series of hypocrisies.

If we want a system that moves people without killing them, we need to start putting our money where our mouths are. We need policies that put safety first, placing everyone’s well-being at the center of our roadway design.

It’s Safety Over Speed Week

Click below to access more content related to our first principle for infrastructure investment, Design for safety over speed. Find all three of our principles here.

-

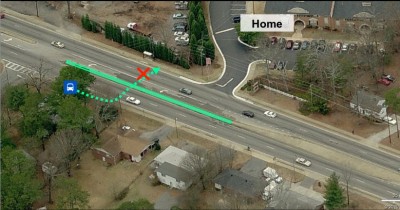

Three ways quick builds can speed up safety

It will take years to unwind decades of dangerous street designs that have helped contribute to a 40-year high in pedestrian deaths, but quick-build demonstration projects can make a concrete difference overnight. Every state, county, and city that wants to prioritize safety first should be deploying them.

-

Why do most pedestrian deaths happen on state-owned roads?

Ask anyone at a state DOT, and they’ll tell you that safety is their top priority. Despite these good intentions, our streets keep getting more deadly. To reverse a decades-long trend of steadily increasing pedestrian deaths, state DOTs and federal leaders will need to fundamentally shift their approach away from speed.

-

Why we need to prioritize safety over speed

Our roads have never been deadlier for people walking, biking, and rolling and the federal government and state DOTs are not doing enough. If we want to fix this, we have to acknowledge the fact that our roads are dangerous and finally make safety a real priority for road design, not just a sound bite.