Our new report examines the racist roots of our current transportation system. Most importantly, it demonstrates how today’s policies and practices were shaped by the past, leading to racial disparities today. Without a fundamental change to the overall approach to transportation, today’s leaders and transportation professionals, no matter their intent, will perpetuate and exacerbate the damage.

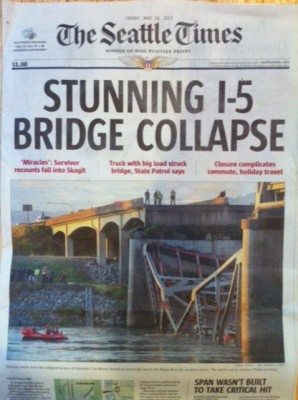

Beginning in the 1950s, highways devastated communities of color and changed our cities forever. But the consequences continue, even as we begin to acknowledge our past mistakes.

To create a better system, we can’t settle for small changes. We need a total shift in approach. To learn more about the report and our analysis, join our webinar on July 25 at 2 p.m. ET.

Read the report Register for the webinarA guide to this report

Part I examines the damage and inequities deliberately created by and in the federal transportation program from ~1950 onward. It concludes with a unique analysis of both an unbuilt and built highway segment within Atlanta and Washington, DC to quantify what was lost, who bore the brunt of the damage, and what could have been lost with highways that were never built.

Part II examines our current transportation program to demonstrate how the programs, standards, models, and measures have their roots in the previous era and exacerbate inequities—whether intentional or not.

Part III outlines what needs to change—concrete steps we can take to fundamentally reorient the program around unwinding those inequities.

Two cities divided

Divided by Design also quantifies the damage caused by highways in two U.S. cities: Atlanta, GA and Washington, DC. Like hundreds of others in the U.S., these cities are forever scarred by highways that demolished communities of color, robbing them of opportunity and potential.

Atlanta’s I-20 displaced over 7,500 people and destroyed 1,400 occupied homes. In DC, I-395/695 displaced over 5,000 people and demolished 2,200 homes. These numbers only scratch the surface of the full damage and dislocation.

More significant damage was also avoided in these cities. To understand what might exist in these communities if they hadn’t been disrupted by highways, we looked at two planned highway segments that were never built and the hundreds of businesses, office buildings, and homes that wouldn’t exist today. Click to read these stories:

The damage continues

The models, policies, and practices we use today took root in the highway era, and they continue to inflict the most harm on people of color. Our approach leads to worse health outcomes, greater congestion, and deadlier roadways. It leaves millions of Americans without access to reliable transportation options to get where they need to go. We can’t build a better system on a rotten foundation. It’s time for a paradigm shift.

We need a new approach.

Read Divided by Design

Explore the report’s full content—jump to one of the three parts with the graphics below.

Don’t miss supplemental maps, videos, and animations in the DC and Atlanta case studies which are not in the hard copy. Download a PDF version of the report.