Artwork along the American Indian Cultural Corridor in Minneapolis, MN.

Artwork along the American Indian Cultural Corridor in Minneapolis, MN.

Transportation for America believes in hands-on learning from experienced practitioners. We put that belief into practice through programs like our Arts, Culture and Transportation (ACT) Fellowship, supported by the Kresge Foundation, where we have been able to take our fellows to different communities to experience first-hand the power of arts and culture to produce better transportation systems.

In late October, our 11 fellows participating in the fellowship visited the Twin Cities in Minnesota to learn from local practitioners using art and cultural strategies to improve transportation. We invited a few fellows to reflect on their experiences. The fellows were able to witness how community members are taking control and how transportation leadership and city government are learning from communities and becoming more responsive, and reflected on how they’ve integrated what they’ve learned into their own transportation projects at home.

Here’s what a few of our ACT Fellows had to share:

Listen to the community. They are the experts.

Sue Lambe

Manager, City of Austin Art in Public Places Program

Austin, TX

Our two days in Minneapolis-St. Paul were filled with meaningful glimpses into local culture, particularly along transportation corridors such as the Green Line in St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood. Rondo, like communities in many American cities in the ’50s and ’60s, was divided by an interstate highway which was constructed along racial lines to divide white people from people of color.

Local activist Melvin Giles. Photo: Sue Lambe

Deeply inspiring local activist Melvin Giles narrated our walk through the Rondo neighborhood and spoke of the fight for equity that the neighborhood has waged for decades. Melvin supports peaceful interaction while working for equity. He shared one of his biggest weapons in waging peace and de-escalation of violence by gifting each of us with a vial of his ever-present bubbles with bubble wand.

Melvin shared many insights with the fellows: the need to remain present through the tough times as well as the good times, his delight in the many friends and neighbors he introduced to us throughout the Rondo neighborhood, the art installations (one featured African American railroad employees) that seek to tell important stories illuminating the history of the African American community. One tiny moment in particular sticks with me and won’t let go: a casual comment about an unassuming empty lot. As we moved along the Green Line that rainy morning, Melvin sort of threw a hand toward a space sandwiched between a restaurant parking lot and an empty storefront, stating that the unassuming grassy lot is the epicenter of neighborhood celebrations, civic events, and political campaign stops.

The “unassuming grassy lot” that hosts community events. Photo: Sue Lambe

For me, this was a revelation. Without his interpretation of this space, as an outsider I would have seen what just appeared to be there—nothing. My current work includes bringing public art to 50 miles of transportation corridors in Austin, TX and my immediate thought was: how will we be able to correctly interpret these “empty lots” in Austin as deeply meaningful spaces?

Melvin showed us one answer: planners, designers, and civic leaders embedded in a space, community, or neighborhood, must spark conversations with those living there in the process of decision making and listen to the wisdom imparted in order to ensure that valuable community resources may remain and be celebrated, possibly with public art. I’m so grateful. Thank you, Melvin!

Taking time to work with intention

Keiko Budech

Communications Manager, Transportation Choices Coalition

Seattle, WA

During our trip to the Twin Cities, our cohort met artists, activists, electeds, and community builders working in the intersection of art and urban planning. The words “community” and “belonging” came up, rooting us back to why we do this work—to create and preserve spaces where people feel a sense of connection and community belonging.

ACT Fellows from Seattle with Minneapolis Councilmember Andrea Jenkins. Photo: Keiko Budech

Community artists and activists Melvin Giles, Missy Whiteman, and Andrea Jenkins all reiterated the importance of having community members and artists as a (paid) part of a planning process (at the beginning stages), and continued to ask the question, “how do you build on assets of the community that are already here?” There’s endless collective and creative wisdom in a community that is often overlooked in urban planning.

A highlight of our visit was meeting artist, poet, and Minneapolis Councilmember Andrea Jenkins. She described a powerful community-based art project in Central and South Minneapolis called ‘This house is not for sale’ that displayed art on realty signs outside of foreclosed homes to spread awareness about displacement in the neighborhood, distributed information about what to do if someone is trying to buy your home, and explored what it means to acknowledge a home’s history. She also shared her experience transitioning as an activist/poet into elected office. She took us on a walk to the bridge over the “scar that splits our neighborhood” (the interstate highway), where she hosts an annual dinner on the bridge to connect her east and west communities. Andrea was full of ideas of ways to use art and culture to bring community together, and reminded us that art can be a powerful agent of community transformation.

Missy Whiteman and the American Indian Cultural Corridor in Minneapolis. Photo: Keiko Budech

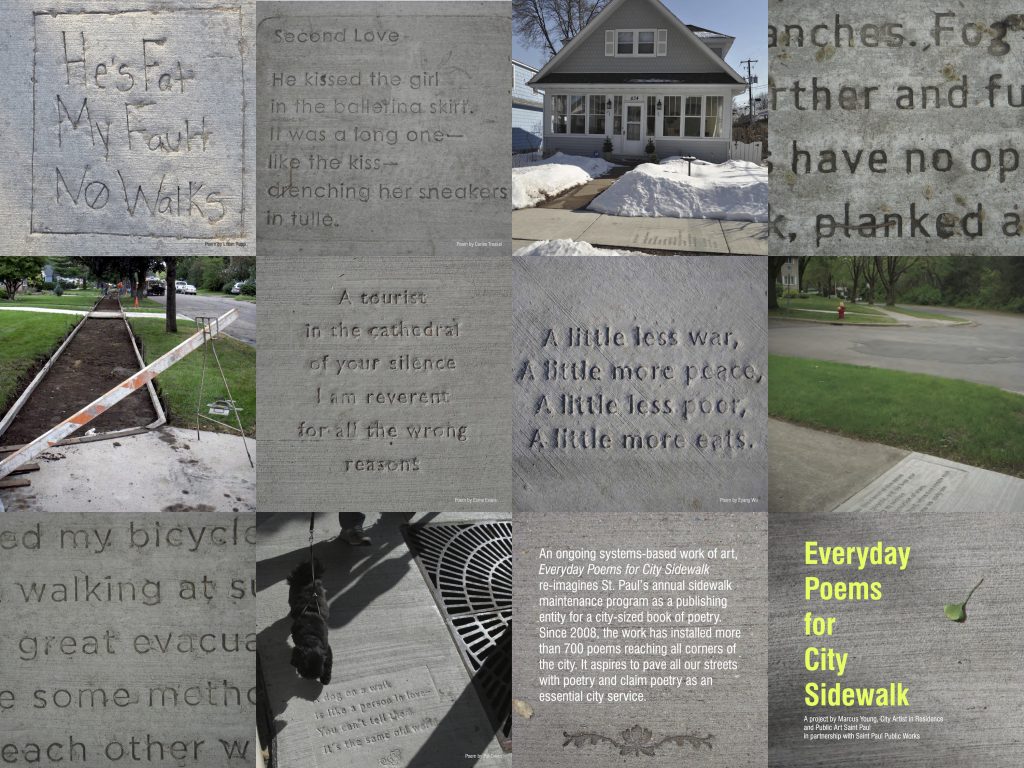

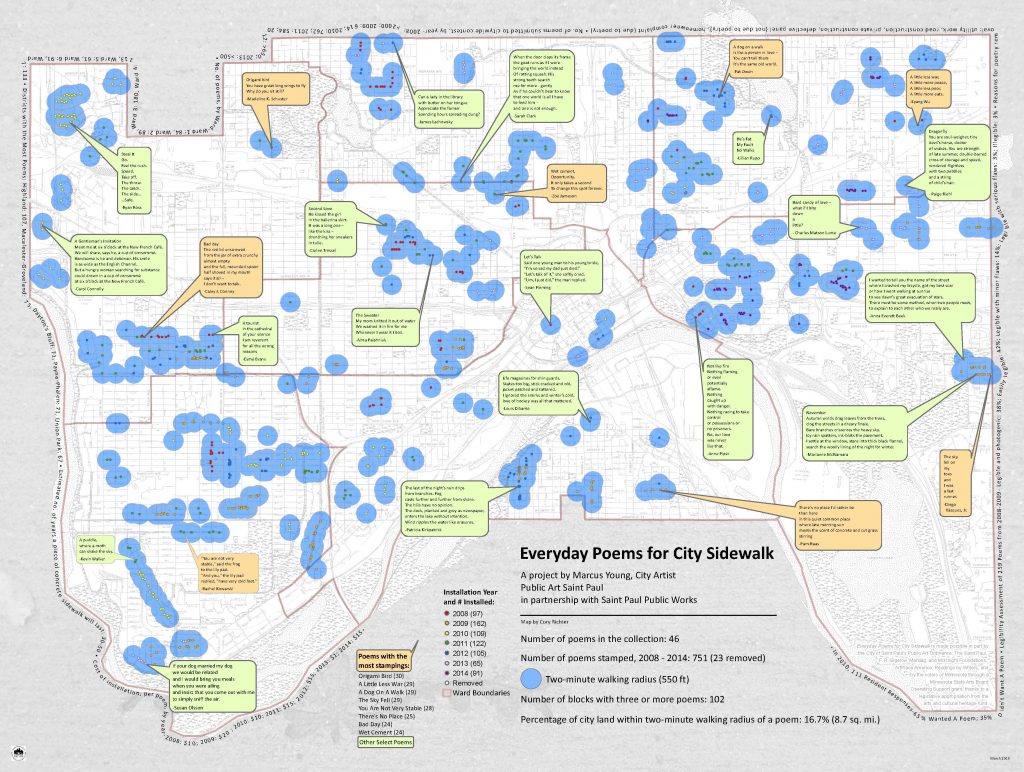

Missy Whiteman, artist and member of the Northern Arapaho and Kickapoo tribes, guided us around the American Indian Cultural Corridor in Minneapolis along East Franklin Avenue. She explained that it’s better to take time on a project and do it right, because big land-use and transportation projects will last for generations. She also emphasized the importance of always working with indigenous community members (again, paid!) on planning projects to understand the history of the land that we are occupying, and what changes we can make to acknowledge and not repeat our oppressive history.

The Seattle fellowship team continues to explore questions around how to create public art that builds on the assets of community, and works to keep low-income communities and communities of color in place when new infrastructure is built (for example, the Puget Sound region’s current construction of our 116-mile regional light rail system). Community-informed public art can be a tool to preserve and celebrate the neighborhood’s history and culture, but if we don’t anchor community with anti-displacement tools, then who is that art work for? It was helpful to connect with experts in the Twin Cities dealing with similar questions, and explore a city with rich public art resources and multiple public art nonprofits, like Forecast Public Art, supporting community artists pursuing public art work.

Integrating on-site learning into projects at home

Erika Wilhite

Artistic Director, En Masse Arts

Springdale, AR

“Development without displacement” mural in St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood. Photo: Sue Lambe.

My favorite day of our convening was led by Melvin Giles in the Rondo neighborhood of St. Paul. They told us the story about Rondo, which was the center of the local black community in the Twin Cities. It was heavily damaged and forever transformed in the 1960s due to the construction of a new interstate highway right through the middle of Rondo, causing the displacement of over 500 families as well as local businesses. Along the way I snapped photos of murals that state “Development Without Displacement” and signs taped to the side of buildings declaring “We will not be moved.” All around there was evidence of a community speaking up, taking their space, and directing the conversation about development.

Our final stop on the tour was the Rondo library, which is where we met with Erin Laberee of Ramsey County Public Works and artist Hawona Sullivan Janzen. They recounted a story about how the city went to the Rondo community for input on a new bridge that was to be built over I-94, but in the process city representatives learned that there was a lot of listening that first needed to be done about the negative impacts that I-94 had on Rondo. The city acknowledged that there was a need to address those wounds and give the community control of the planning process. I am especially impressed that they scrapped their original timeline and extended the community input process to listen as long as it would take. I love this story because it is an example of how community-led development can create the conditions for healing and neighborhood development.

Concept for a land bridge or cap over I-95 in St. Paul, MN.

Since the trip, I have since learned more about ReconnectRondo, an organization in place to steward the community engagement and also cast a much more ambitious vision of a “land bridge” to place a cap over I-94 at several spots to reconnect the divided neighborhood, create new meaningful gathering spaces, and “leverage the potential of the Rondo Land Bridge and the numerous innovations, partnerships and policy changes in transportation, to see a sustainable and thriving community for us all!”

I see how the current conversation about transit in my community, Springdale, Arkansas, was rushed, and how we are missing opportunities to create conditions for community cohesion. I have shared these stories from Rondo and used them to rebut the claim that the process for community engagement can’t be amended once it is underway. There were many projects and stories of collaborations in the Twin Cities that I take away as examples of community-led, artist facilitated, development processes to share with my community and the NWA Regional Planning Commission (our metropolitan planning organization) of what equitable transit planning looks like in action.