Even if we hit the most ambitious targets for changing our cars and trucks over to electric vehicles, we will fail to meaningfully reduce emissions from transportation without confronting this simple fact: new roads always produce new driving. This costly feedback loop referred to as “induced demand” is the invisible force short-circuiting the neverending attempts to eliminate congestion by building or expanding roads.

Today, Transportation for America is partnering with RMI and the Natural Resources Defense Council to release a new calculator that shows how highway expansion repeatedly fails to reduce congestion and instead increases traffic and pollution. The SHIFT Calculator provides transparency about new traffic created by highway widening and expansion so transportation agencies can make smarter, more sustainable transportation investments. Read the press release.

Imagine a guy who, struck with a wild but charitable fever of generosity, decided to give away 100 gallons of tasty, free coffee every morning at a small downtown stand. During that entire first week, he struggled to give it all away before lunchtime and went home with quite a few gallons of leftover lukewarm coffee. In week #2, he started seeing familiar faces each day from the nearby buildings, because people walking by know a good deal when they see one (the low price of free!) Many of them returned each day and the coffee was gone by 11 a.m. By the third week, the word was out across downtown about the “crazy free coffee guy” and he started running out earlier each day. By the start of week four, people were coming from all over downtown and he had a line queued up waiting for him at 7 a.m. to ensure they got their free cup before work, and it was all gone before 9 a.m.

Say hello to “induced demand.”

Giving something away for free shapes the behavior of those who want it

It’s a fundamental principle of economics: Provide a tangible good at no cost that people value and the demand will outstrip supply.

Yet political leaders and transportation agencies refuse to believe that this same basic principle will apply when they spend billions to widen or expand highways in the name of “solving” traffic congestion in urban regions, and then give away all of that newly created space for free. They refuse to believe that anyone will take new trips on the newly freed-up highway space, that people will shift existing off-peaks trips to rush hour, that someone on transit might decide to return to driving (like thousands of people did during the pandemic), or that developers might take advantage of the new capacity to build yet more houses or retail on land that’s now more easily accessible.

They refuse to believe that this is possible, even when all of that expensive new highway space fills right up in a short period of time, wiping out any benefits and failing to deliver on all those promises of speedy commutes, improved travel times, and money in our pockets from all the “time savings.”

Attempting to “solve” congestion by building new roads or expanding existing ones has been the animating purpose behind billions of dollars of federal and state transportation investment for decades now.

Armed with this single-minded purpose and billions in no-strings money from the federal government, states have spent hundreds of billions of dollars to widen or build new highways. We built enough new roads and lanes from just 2009-2017 to build a brand new road back and forth across our enormous country 83 times. State transportation departments have added 5,325 new lane-miles just since 2015.

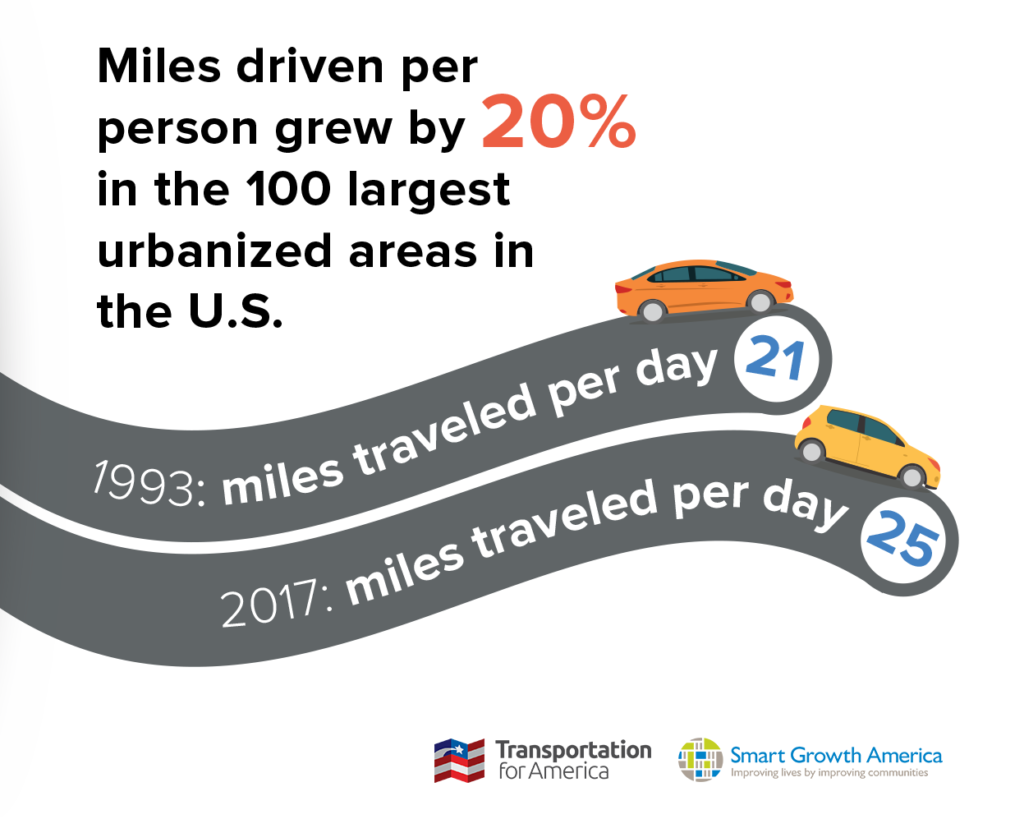

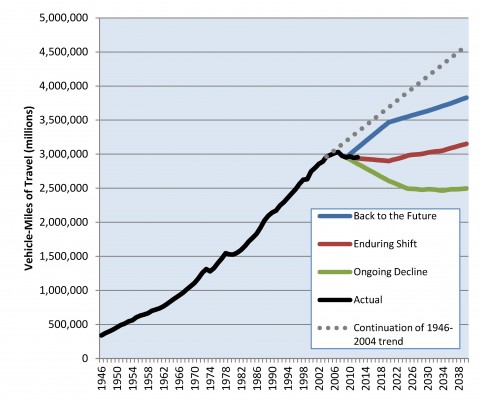

All the lanes we’ve built have led to a predictable increase in driving. From 1980-2017, per capita vehicle miles traveled (VMT) increased by 46 percent. In 1993, on average, each person accounted for 21 miles of driving per day in those 100 urbanized areas. By 2017, that number had jumped to 25 miles per day. Every year, Americans are having to drive farther just to accomplish the same things we did back in 1993 every day.

The problem isn’t too few roads

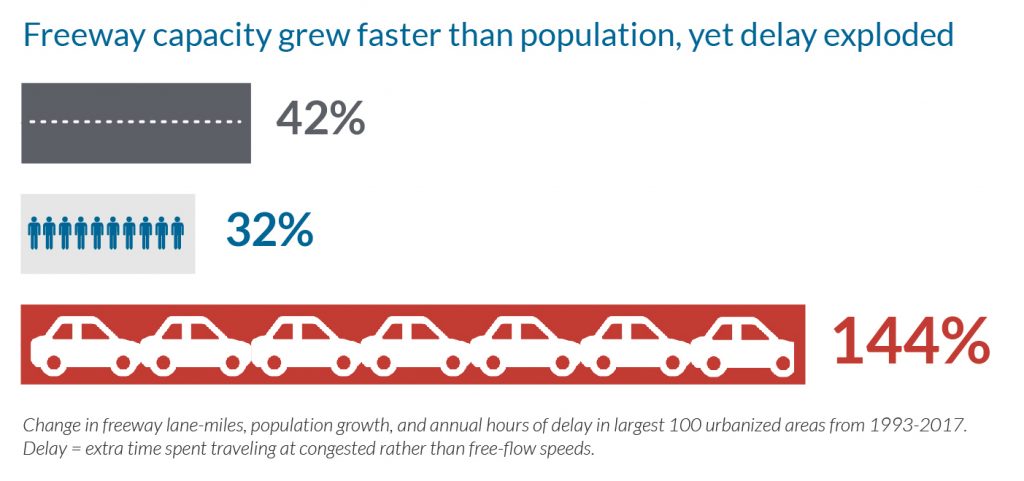

Delay skyrocketed in our 100 largest urbanized areas from 1993-2017, rising by 144 percent. Yet we expanded our freeway system in those areas by 42 percent, while the population only increased by 32% during that time. We built roads like crazy, yet delay just got worse.

Delay increased because new highways, roads, and lanes are proven to induce more driving, which leads to more emissions and ultimately more congestion. The evidence for induced demand is overwhelming. In a landmark study, Kent Hymel at Cal State Northridge suggests the relationship is perfectly correlated—a 10 percent increase in lane miles leads to a 10 percent increase in driving.

If you’re celebrating the notable but small climate and transit provisions in the current enormous infrastructure deal, you should know that this shortsighted 1950s-style deal will provide states with historic levels of virtually no-strings highway funding that they can continue to blow on the same old bankrupt strategy for congestion without even any basic requirements to repair things first.

Profligate spending on highways also undermines the relatively limited investments being made in other lower emission transportation options like biking, walking, and transit.

Why do transportation agencies deny this reality?

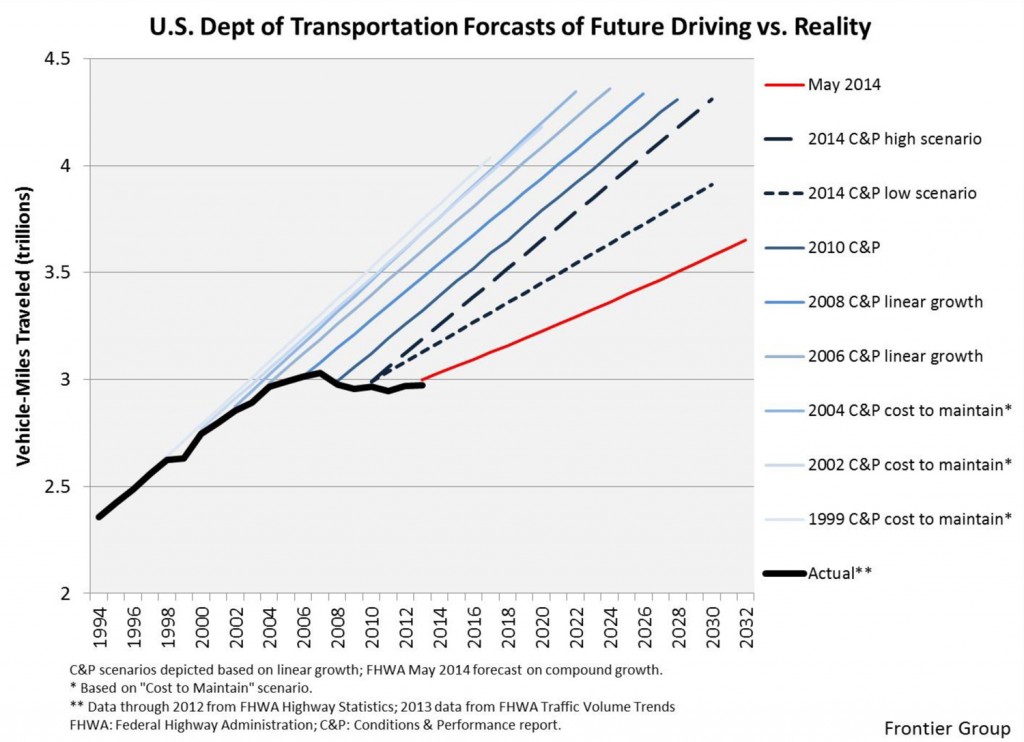

The unreliable models that agencies depend upon have a poor track record of success, but they never look backward to consider their accuracy or how they can be improved. When is a state DOT ever held to account for repeatedly making predictions about traffic that fails to materialize? Who even remembers what they predict? This great thread from Kevin DeGood about Texas DOT’s repeated failure to make accurate predictions shows just how rarely anyone looks backward:

1/ TxDOT is pushing hard to widen I-35 based, in part, on traffic forecasts that show doom and gloom. Reader, you should be deeply skeptical since TxDOT has missed the mark for decades. Let’s take a look. pic.twitter.com/9RxLLGmHrI

— Kevin DeGood (@kevin_degood) October 12, 2021

19 years ago, the Texas DOT predicted that average daily traffic (ADT) on I-35 through downtown Austin would be 330,000 daily vehicles by last year. The reality wasn’t even close: Actual totals in 2019 were only 201,000 daily trips. As Kevin notes, in 2016, with the state totally ignoring how wildly inaccurate their current projections were turning out to be, they projected “that total VMT on I-35 in the Austin area would increase by 50% by 2040.”

Rinse and repeat.

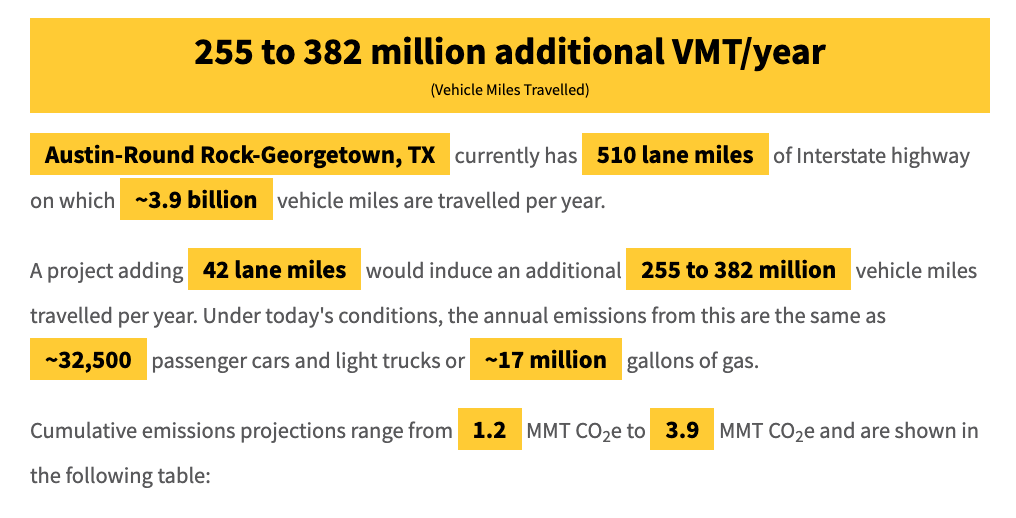

TxDOT is certainly doing their best to make those 2040 projections come true. All it’s going to cost taxpayers is $5 billion to widen I-35 right through downtown.

If the state follows through on this staggeringly expensive project, they’d be creating millions of new trips and increasing pollution, all while failing to make a dent in congestion over the long term and wiping out hundreds of acres of some of the most valuable land in the entire state.

The cynical answer to “why” is that if state DOTs around the country finally admitted that expansions fail to actually solve congestion, they would lose their #1 strategy of continued expansions that allow everyone other than the taxpayer to make more money. They’d be admitting that they’ve placed all of their bets on a losing horse, and they’ve been doing so for years. On top of that, they’d then have to do far more sophisticated work to better understand the complicated reality of our travel needs and rebuild their models from the ground up to focus on moving people rather than just “make cars go fast.”

Even the most progressive states with ambitious agendas to lower transportation emissions aren’t fully willing to acknowledge this reality.

Advocates and residents and local leaders need to start holding them to account. How?

We can’t put our heads in the sand anymore

This new, rigorously vetted calculator produced by RMI, the Natural Resources Defense Council and Transportation for America provides more accurate and transparent data about increases in driving and pollution, as well as the other impacts of highway expansions.

Our hope is that advocates, local governments, and anyone who cares about finally getting more accurate and transparent data about increases in driving and pollution will use this new tool to hold their transportation agencies to account. And we want transportation agencies to use it to bring a fuller picture to their current transportation modeling that leads them to “solutions” that fail to address congestion, divide neighborhoods, increase pollution, devastate nearby communities, and fail to meaningfully improve our access to jobs and services.

Find a proposed project in your metro area and run it through the calculator.

Some parts of the above post were adapted from Driving Down Emissions, a report from Smart Growth America and Transportation for America which explores how changing transportation policy and land-use patterns are key to lowering greenhouse gas emissions.