With the bipartisan infrastructure deal approved by the Senate, opportunities to shift long-term transportation policy will shift to the House and to program implementation. The opportunity in the House is through targeted investments via the budget reconciliation bill that will accompany the House infrastructure bill vote.

(UPDATE 8/18: Clarified details on the passage of the Affordable Care Act)

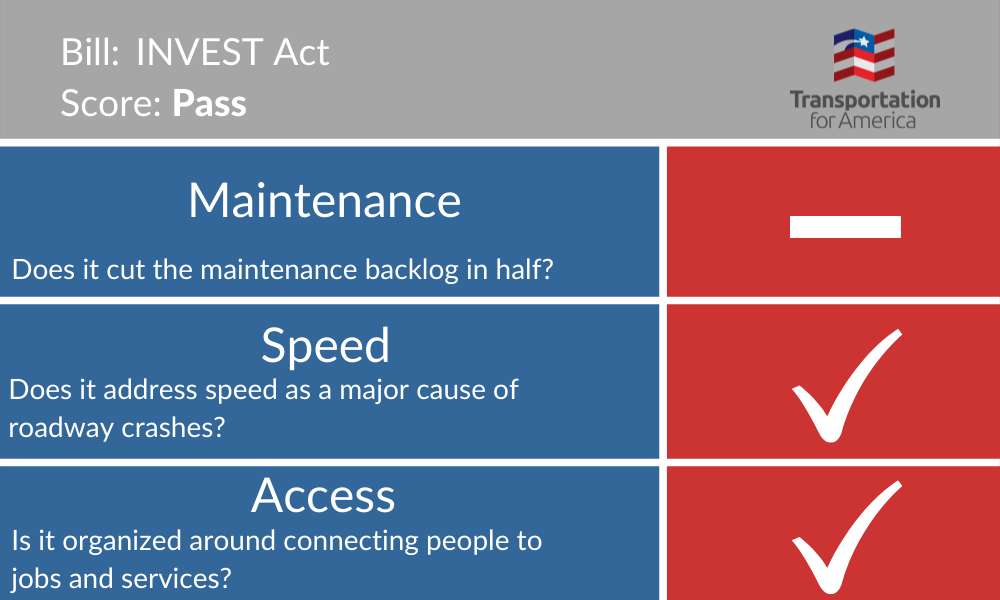

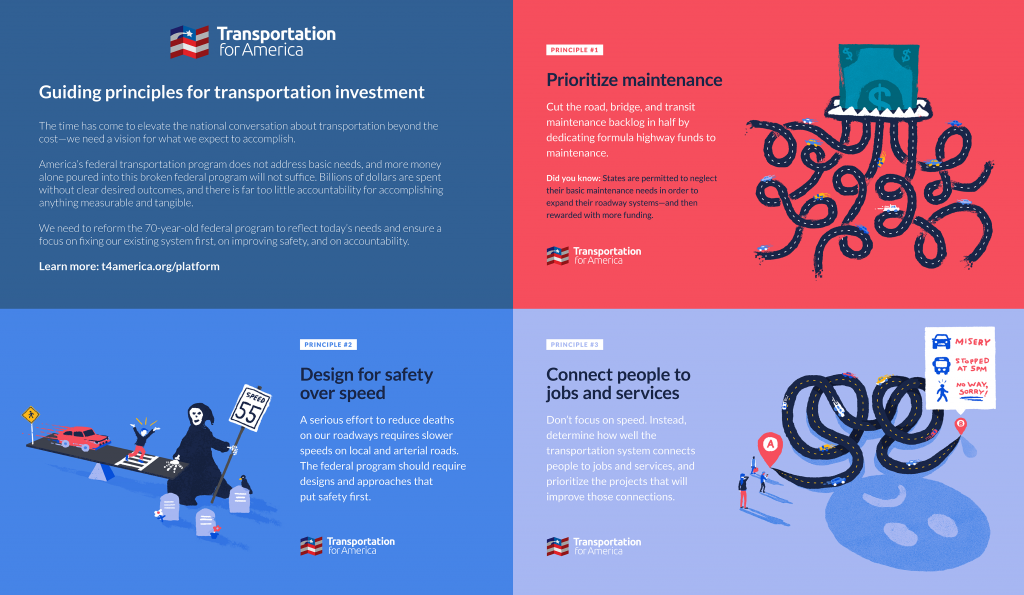

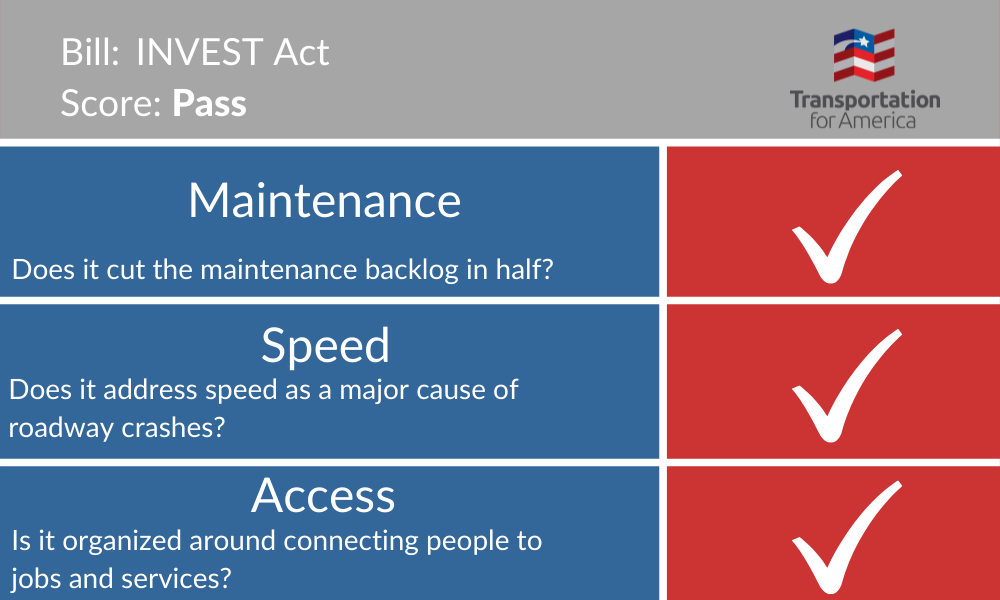

After a strong five-year reauthorization proposal was approved by the House, the Senate transformed their reauthorization offering into a larger bipartisan infrastructure deal, funding everything from broadband to water infrastructure, which passed the Senate last week. This deal, which was crafted and passed in the Senate with the White House’s backing, doubled down on maintaining the status quo in regards to transportation policy, focusing on highway construction and expansion without incorporating maintenance of roads and bridges as the priority, improving transportation safety, and better connecting communities.

Rep. Peter DeFazio criticized the deal, specifically citing the bill’s treatment of public transportation.

Speaker Nancy Pelosi reportedly refused to approve the Senate’s deal, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act without the Senate first approving a sweeping budget reconciliation bill that focuses on strategic national investments across a broad spectrum of infrastructure concerns, including but not limited to agriculture, environment (air and water), education, first responders, and public health. The Senate granted her wish, passing a budget resolution, kicking off the reconciliation process, and this bill provides an opportunity to invest more in transit funding, including transit operations.

What is budget reconciliation?

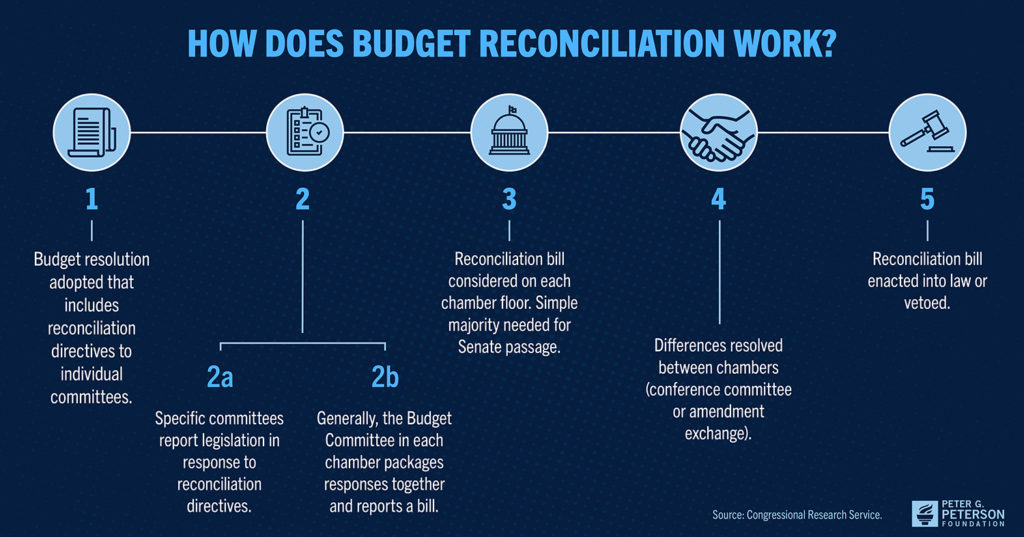

As noted in the graphic below, the Senate budget resolution provides key directions to specific committees on both the House and Senate side on how to program the specific budget called for in the resolution. (Budget reconciliation is often used to pass more controversial or partisan legislation. For example, the final Affordable Care Act package resulted from the House passing the Senate’s healthcare bill and then amending it through the reconciliation process. However, reconciliation only happens once each year as part of the annual budget-making process.) The House will return next week, with respective committees deliberating how they will program and craft legislative text to the directives of the Senate’s budget resolution, before cobbling together the final reconciliation bill for passage in both chambers of Congress.

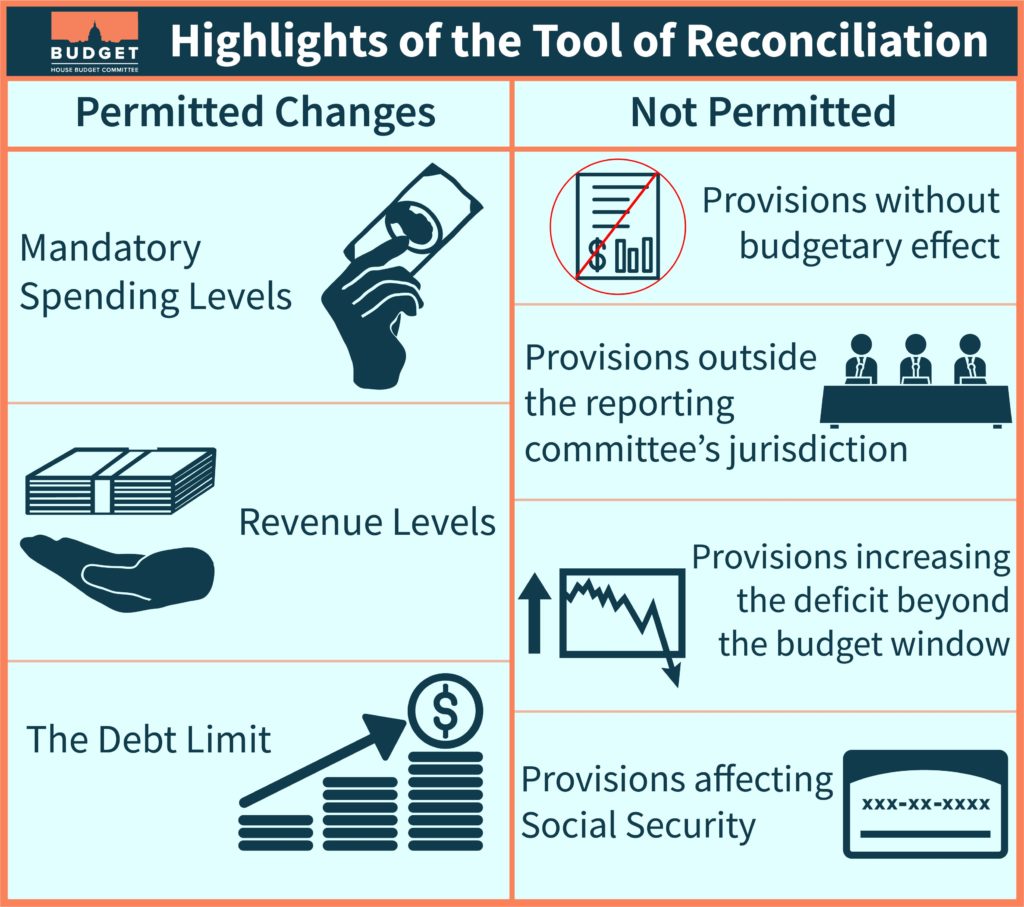

As the respective committees in the House and Senate contemplate legislative text for the final reconciliation bill, there are key restrictions for what can be included. Unfortunately, introducing brand new policies or making major policy changes not connected directly to new funding are difficult if not impossible.

As the graphic illustrates, any legislative text in the final reconciliation must pertain to policy that has budgetary impacts and stays within the programming directions and funding limits of the budget resolution.

As it pertains to transportation, the resolution allocates $60 billion to the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee to program as they deem prudent, while also adding unspoken pressure not to revisit items called for in the IIJA. The resolution also calls for an additional $30 billion for respective Senate committees focused on surface transportation to program accordingly.

Within those constraints in place for this reconciliation process, T4America has outlined three key investments that need to be made to better connect communities and improve equity and climate outcomes.

1. Increasing public transportation funding levels by $10 billion

The original bipartisan infrastructure framework, agreed to and announced by the President and the Senator’s part of the negotiations in June, called for $49 billion for transit. As the final IIJA was set, transit was the only part of the plan that took a cut (of $10 billion) from that original proposal, down to $39 billion. Less money for transit means greater challenges for transit agencies, for keeping transit running, and making the necessary capital investments, including transit electrification. There is much more that can be done to improve transit, but advocating simply for restoring the agreed funding amount is an easy fix within the limits of the budget resolution.

2. Increasing funding for the reconnecting communities program by $12 billion

President Biden’s American Jobs Plan (AJP) contained approximately $24 billion for reconnecting communities (tearing down highways that separate marginalized communities, reintegrating community mobility and streetscapes). The Senate’s deal slashed that program down to just $1 billion. (The House’s INVEST Act allocated $20 billion.) By restoring at least some of this program’s funding, meaningful progress can be made to reconnect and reinvest in diverse communities across the United States.

3. Increasing funding for zero-emission vehicles and charging infrastructure by $7.5 billion

Currently, transportation is responsible for a significant portion of climate change-inducing emissions, but emerging technologies are making it possible for reliable zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs). Meeting the moment with significant investments in ZEVs (especially medium and heavy duty vehicles such as transit, school bus, and municipal fleet vehicles) and their associated charging infrastructure will help drastically curb emissions. This funding would also involve investments in domestic manufacturing to help ramp up capacity and lower costs to deliver on ZEVs and their charging infrastructure.

While Congress is in recess and members are in their home districts, it is a great time for constituents to engage their members on these issues. Share these three simple, key investment priorities for reconciliation with your members of Congress, while explaining what these investments can mean in your local community in regards to jobs, equity, and climate change.