Transit agencies across the United States have struggled with decreased ridership, safety hazards, and low morale as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet some have responded by changing their approach to better serve everyday riders, make transit free or more affordable, and rethink what the future of transit should look like to reduce emissions and provide access for those who need it most.

This post was written by Devin Willis, program associate at Smart Growth America. It is the fourth of a series of posts on this topic—find the full set here. Some of the agencies profiled in this piece were interviewed with support from the Kresge Foundation.

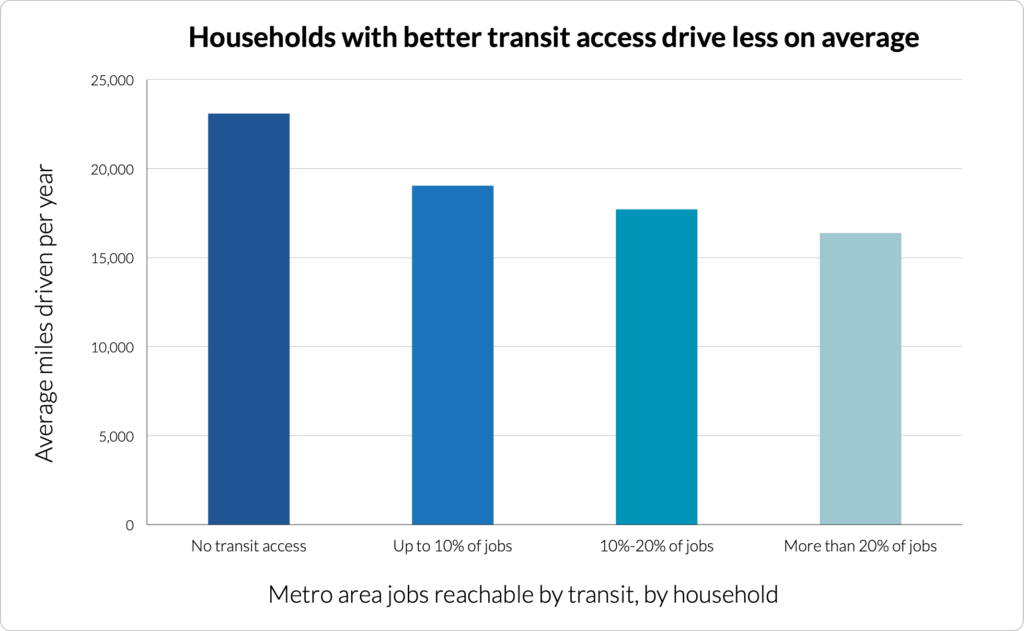

This series has explored how public transit is an essential part of mitigating climate change by reducing emissions. Connecting more people to their everyday destinations via public transit offers a way to cut back on vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and transportation emissions.

We’ve been writing this series against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has presented unprecedented challenges for transit agencies and the millions of riders they serve. Transit providers all over the country are struggling with revenue loss due to the massive ridership drop in 2020, service cuts, driver shortages and illness, vaccine skepticism, and low morale. Although the funds for transit in the 2021 infrastructure bill will help, those funds can’t help fund operations for most transit agencies or undo the damage caused by the pandemic. (The American Rescue Plan, passed during the pandemic, does specifically provide emergency operations support for transit agencies.)

This is a slight detour from our series about the potential of reducing emissions with more transit, but we wanted to profile a few transit agencies that shifted their approach during this historic pandemic to provide better access for their riders and rethink the future of transit in their communities—both of which are stepping stones to more significant improvements that can help reduce emissions.

Richmond, VA preserved ridership levels with fare-free transit and a past network redesign

Unlike many transit agencies nationwide, Richmond’s public transit only suffered a relatively modest drop in ridership, and has already recovered local bus ridership to pre-pandemic levels. This is likely due in part to a handful of bold actions on the part of the city government and the Greater Richmond Transit Company (GRTC). GRTC CEO Julie Timm, hired just six months before the pandemic, attributes their success to three main steps taken:

1) The strength of the 2018 network redesign connecting essential workers to jobs; 2) the extensive COVID protective measures enacted early and throughout the pandemic to protect staff and riders; and 3) the ongoing commitment to Zero Fare operations to protect the health and financial stability of our riders. GRTC’s focus on connecting people to essential resources resulted in higher sustained ridership.

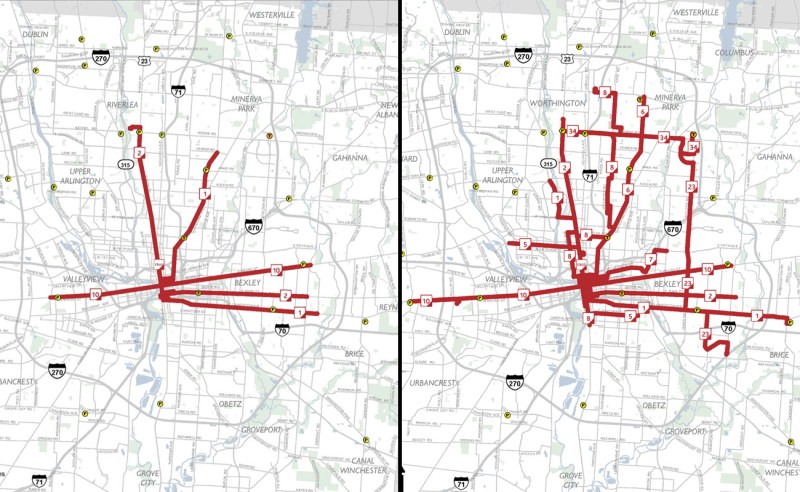

As Timm notes, before the pandemic in 2018, GRTC implemented a significant redesign of its bus routes to improve access and produce faster, more consistent service. Their redesign includes new route names and numbers (routes are now named after major roads that are well known to locals like Hull Street), increased bus frequency, and easier connections. This service redesign successfully produced an increase in ridership every month between June 2018 and February 2020, reaching a full 29 percent increase over that time period and providing a solid foundation to build upon during the difficulties of the pandemic.

The most notable change that GRTC made during the pandemic was the decision by the GRTC and Mayor Levar Stoney in March of 2020 to suspend all fare collection from bus riders. In Richmond, the majority of the bus service ridership and revenue comes from the often economically distressed households of essential and low-income riders. This shift to 100 percent free transit spared many families and workers from having to choose between their bus fare and other needs like food, medicine, and employment access.

While Richmond was not the only city to introduce fare-free policies during the pandemic, GRTC is among the more successful cities to do so, effectively preserving the city’s bus ridership and maintaining the zero fare policy longer term. And two years later, GRTC is continuing to offer fare-free transit while most other cities that did so have since returned to their previous fare policies. The GRTC was awarded $8 million in state grant funding from the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation to continue experimenting with the effects of zero fare policy over the next three years through June of 2025. The City of Richmond and Virginia Commonwealth University have agreed to match this funding in support of the zero fare policy and its positive effect on bus riders.

Atlanta, GA looks to restructure service to respond to changing needs

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Agency (MARTA) had approximately 110 bus routes with over four million passengers per month. In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic MARTA, like many other US transit agencies, watched ridership crater. And in the intervening two years of the pandemic, they have struggled to bring their ridership back to pre-pandemic levels. At present, MARTA’s ridership is approximately 65 percent of pre-pandemic levels.

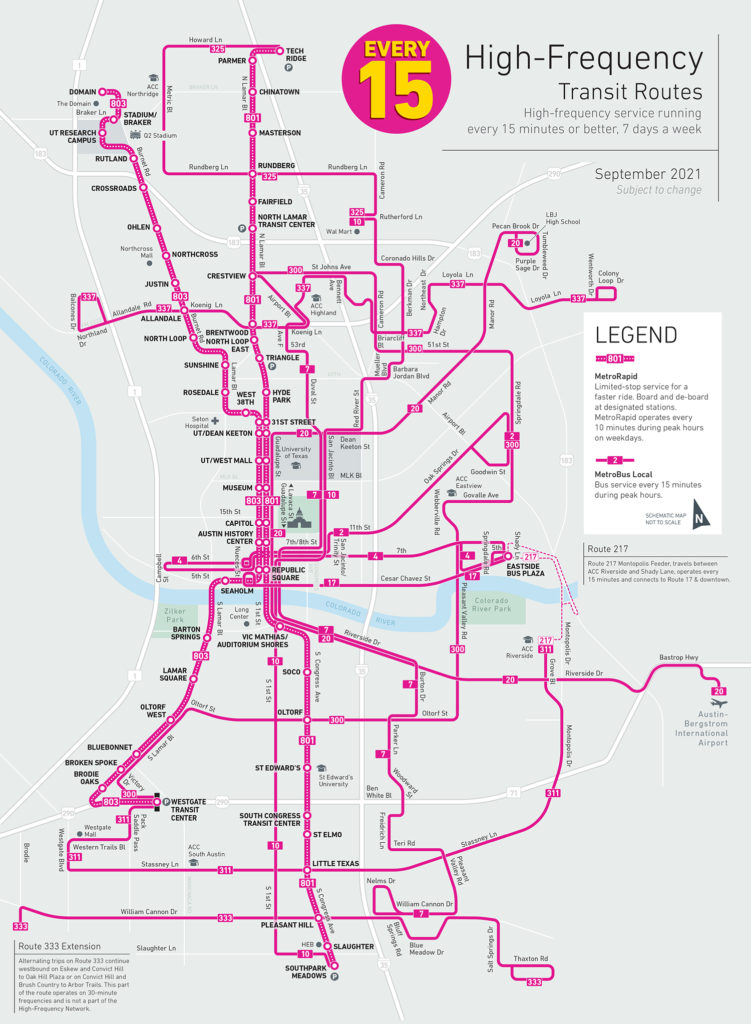

Similar to Richmond’s 2018 redesign but taking place during the pandemic, MARTA launched a major initiative to restructure bus service as a response to the pandemic and to better address the needs of residents. MARTA is currently leading a major online and in-person community engagement effort, soliciting feedback and ideas regarding new potential bus routes and service types. MARTA is posing key questions to its riders directly about the tradeoffs between service frequency and breadth of coverage directly: do riders want to see fewer routes with more reliable, frequent service between highly-trafficked areas (similar to the changes Richmond made, as well as Columbus and Houston) or more routes in more neighborhoods but less convenient service on those routes? Following the engagement, the proposed redesign concept will be released in the spring of 2022.

In addition to the bus network redesign, MARTA has also begun to experiment with mobile ticketing and fare collection to ensure the wellbeing of transit operators and riders. The agency added a mobile ticketing system in order to make transit use more contactless and limit the spread of coronavirus. MARTA hopes to make these changes permanent.

Pittsburgh, PA reroutes buses to better serve low-income riders

Pittsburgh’s Port Authority of Allegheny County lost 80 percent of its ridership during the coronavirus pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, the Port Authority’s transit network was historically focused on connecting suburban commuters to downtown Pittsburgh from residential and suburban areas in the surrounding region. When the pandemic hit and many of those office jobs switched temporarily or permanently to remote work, this type of commuter ridership dried up almost completely.

Like many other transit agencies, the pandemic spurred the Port Authority to reconsider how best to serve its lower-income passengers who rely on public transportation and may not have other options. Pittsburgh increased bus and rail frequency for 37 percent of the neighborhoods within its service area. This is part of a larger shift away from commuter routes and toward providing more service in low-income neighborhoods. Pittsburgh’s transit agency has also added more off-peak and weekend hours to accommodate riders who do not work on a 9-to-5 schedule.

The Port Authority also implemented changes in the fare system to encourage different types of riders to use the bus system. They recently introduced a modest fare proposal that would restructure the bus fare pass from a calendar-based weekly and monthly pass system to a more flexible 7- and 31-day pass system. This move is a good first step as it removes the bus pass from the commuter-centric five-day week and allows the bus system to better serve non-commuters such as persons traveling on the weekend or outside of rush hours. Locals have pushed for even more significant changes, including fare-free service or a similar policy. One proposal recommends that fares be limited for low-income passengers who are SNAP/EBT beneficiaries.

What’s next

The steps these agencies have taken are examples of what other agencies can do to increase ridership and safety in the pandemic. While the challenges faced by transit agencies during the COVID-19 crisis are very real and there are not easy solutions, the agencies profiled here were able to respond to the changing needs that they observed, focusing on providing access for those who need it most, potentially reducing emissions in the process by improving access and ridership. This type of responsive, nimble approach to transportation infrastructure will help make transit a viable alternative to driving and will help us reach our climate goals.