Because of a mistake by Congress in the 2021 infrastructure law, 40 percent of the new $1 billion-per-year Safe Streets for All program must be directed to planning rather than constructing tangible infrastructure projects. A clarification that the planning grants can support quick-build safety demonstration projects presents an enormous opportunity for cities and towns to directly tap the available $400 million and experiment with low-cost temporary street safety projects. This is the first of two blogs regarding opportunities to use this funding. To learn more, read part two here.

Cities and towns can typically make street safety improvements in one of two ways: they can spend their own local money on streets that they control, which comes with its own set of challenges, or they can engage their state DOT which controls federal formula transportation dollars and many of the most dangerous streets. The new Safe Streets for All (SS4A) program was so crucial because it created a new way for cities, towns, and counties to directly access federal funds to quickly create and execute on Vision Zero plans.

After Congress’s mistake requiring 40 percent of SS4A to go toward planning grants, USDOT wisely broadened their definition of planning to include demonstration projects. This creates an incredible opening for cities to receive funding to pilot temporary street design changes.

The program has $5 billion over the life of the infrastructure law, or about $1 billion per year. The next round of funding is expected to be made available this month, and cities of all sizes should consider applying for planning grants that can support quick-build demonstration projects.

What are quick-build demonstration projects?

Quick-builds, also known as demonstration projects or tactical urbanism projects, are temporary, low-cost improvements to test new changes to street design.

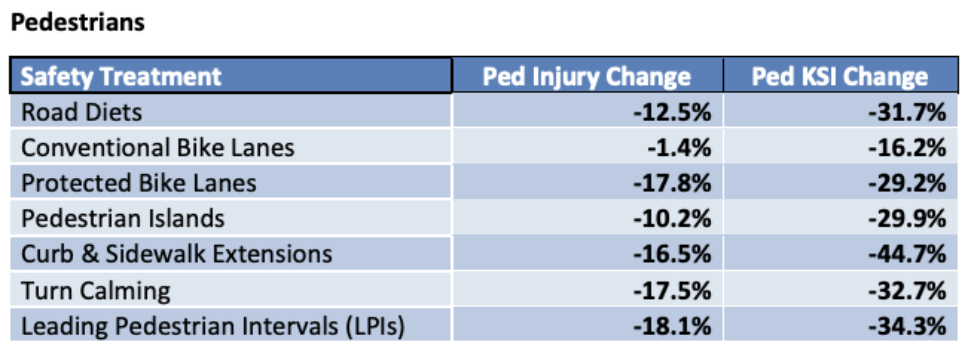

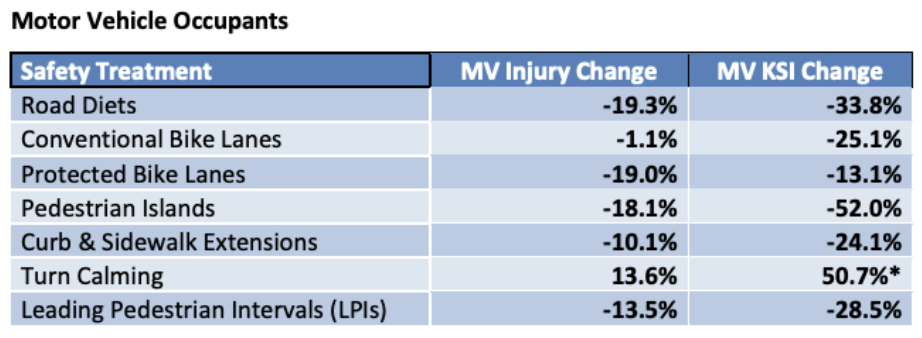

These quick, light, flexible, adaptable projects allow everyone involved—community members, transportation staff, elected leaders—to test specific designs and interventions that measurably improve safety and convenience for everyone who uses the street, all while gathering valuable feedback. They incorporate methods and designs that are proven to reduce crashes, injuries, and fatalities—documented and supported by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA).

Even though temporary, these projects are a vital first step toward making real, tangible changes. And many demonstration projects often end up staying in place indefinitely, or (more typically) forming the basis of the design for a permanent project to come later. The process of creating and executing them builds new knowledge and partnerships—within the transportation department and even with other jurisdictions, related agencies, and advocates—that are vital for building permanent projects.

Why should a community consider quick-build projects?

Doing something concrete—even temporarily—is a powerful way to improve safety for people walking, biking, rolling (and driving), and demonstrate an ongoing commitment to protecting all road users. It also shows how stemming the tide of preventable traffic deaths and injuries requires immediate action, creativity, and a willingness to test new things. Despite the urgent need to make streets safer immediately, even the most simple, common sense projects to build new crosswalks, widen sidewalks, add a new bike lane, or make other improvements for safety and convenience can take a lot of time and money.

Quick-build projects are one way to make some level of improvement nearly overnight at an incredibly low cost, while providing a venue for gathering valuable feedback, testing the impact of the changes, and surfacing potential pushback from community members who might oppose a permanent project. In some cases, quick-build projects end up staying in place until capital budgets and planners can execute a permanent project.

Smart Growth America will soon be releasing a summary of their 2023 Complete Streets Leadership Academy, where they worked with 10 cities and four state DOTs to design quick-build demonstration projects on state-owned roads. Stay tuned!

Demonstration projects can also be incredibly cheap. We’ve supported numerous successful demonstration projects over the last few years with grants as low as $5k-15k. Imagine what a city could do with $1 million to support a Vision Zero planning effort that’s paired with as many demonstration projects as they can build with several hundred thousand dollars?

Nearly $1 billion will be available for planning grants alone

The notice of funding availability (NOFO) from the US Department of Transportation is expected to be released sometime in February, so cities, towns, counties, metro areas or others interested in putting an application together should be getting their act together now. Unlike other USDOT grant programs that are oversubscribed, this one is far less competitive: Nearly every jurisdiction that applied for planning grants so far has been awarded funds.

In fact, over the first two rounds, USDOT didn’t receive anywhere close to $400 million in applications for planning grants. This means that nearly $450 million is rolling into this round and between $900 million and $1 billion is expected to be available for planning activities (and demonstration projects!) in this round alone. That’s an enormous sum.

This is only a temporary fix—in more ways than one

Congress made this mistake, and Congress will have to be the one to fix it. But a legislative fix is a long shot and changes to the makeup of Congress or the administration next January could complicate things further. This is just the second year of SS4A funding, and many cities already have Safety Action Plans created. As more planning funds are awarded, cities will need more capital grants instead of planning dollars. A million more demonstration projects would have a significant impact, but we need permanent changes on our streets, and more of the SS4A program should be devoted to making those permanent changes.

Finally, while demonstration projects are productive for all the reasons listed above, they’re still just short-term solutions to the long-term crisis of streets that are unsafe and inconvenient for people to use without a car. The best quick-build projects will make people safer today while also supporting and advancing local plans to apply for future implementation dollars, or create a foundation for other long-term solutions to address fatalities.