The following post was written by Mehr Mukhtar and London Weier.

Recent record-breaking temperatures demonstrate that we can no longer rely on old design approaches to meet the needs of our communities. Transportation infrastructure is no exception. Extreme heat can cause road surfaces to buckle and rail tracks to warp, leading to significant travel disruptions and safety concerns for commuters.

The heatwaves this past summer, where temperatures soared to record highs in the eastern and western parts of the US, starkly highlighted the vulnerability of our transportation infrastructure designed to meet the demands of past climate trends, not the trends we see today.

Sweltering heat has pushed transportation infrastructure, from roadways to railroads, to the brink, potentially leaving thousands of travelers stranded in the aftermath. Extreme heat has already caused major damage and disruptions, from planes being unable to take off in Phoenix to pavement buckling in Minnesota. Amtrak, too, recently witnessed service disruptions across the Northeast Corridor, and WMATA announced widespread delays in service. Asphalt and metal rails can expand and buckle under high temperatures, creating potentially unsafe travel circumstances. This results in delays caused by the need to reduce speed levels of train cars in the heat, brought about by the need to reduce speed levels of train cars in the heat, impacting travel plans for commuters. Extreme heat and other climate change induced weather events, such as rising sea levels, are poised to drastically increase the costs of maintaining, repairing, and replacing transportation infrastructure—at a time when the nation is already behind on roadway maintenance and repair.

Transportation infrastructure can also exacerbate the effects of extreme heat on our communities. The urban heat island effect, which occurs in urbanized areas, is partly caused by the large amounts of heat-absorbing materials found in buildings and roads. The impacts can make these heat events drastically more extreme, with pavement reaching temperatures of 160° F when the outdoor temperature breaches 100° F.

Community impacts

The impact of heat waves is not limited only to infrastructure. During the heatwaves this past June, over 30 million people were subjected to extreme heat advisories and their deadly effects as treacherously hot conditions persisted across the country. People walking, biking, or utilizing public transit are especially vulnerable to the health risks associated with extreme heat.

Imagine a bus user, navigating their typical commute on a record hot day where temperatures are breaking 100° F. The five-minute walk to the bus stop in the sweltering heat causes sweat droplets to form as soon as they leave their home. The sunlight bounces off surrounding buildings and structures, creating an almost blinding light, and fatigue sets in immediately. These conditions, exacerbated by the delay of a bus, or non-shaded shelters, can spiral into emergencies, such as heat exhaustion or heat stroke.

Often referred to as the ‘silent killer,’ extreme heat has profound health risks due to its effect on the body’s ability to regulate internal temperature. Health impacts of extreme heat disproportionately harm low-income communities and communities of color, as emphasized in a recent video released by Smart Growth America on the disparate burden of extreme heat experienced by communities in Atlanta. Low-income neighbors and communities of color more often lack trees, shade, and natural landscapes that can reduce the urban heat island effect. For some, a hot day means driving instead of taking transit, but for others, that option is nonexistent, and they are forced to endure the high temperatures out of necessity. Communities can use tools, such as the CDC’s Health and Heat Tracker, to determine if they are more vulnerable to extreme heat and develop their own heat preparedness plans (advice for decision makers on how to develop a heat preparedness plan can be found here).

At a recent congressional briefing on extreme heat resilience for community well-being co-hosted by the American Public Health Association and Massachusetts Senator Ed Markey, experts brought these impacts to the attention of federal legislators. At the core of Markey’s opening statement was the sentiment that “prevention is preferable to cure,” highlighting the importance of both responding to climate change-induced warming and reducing carbon emissions in order to avoid exacerbating climate conditions. It is clear that we will continue to contend with increased and more intense heatwaves in the future, requiring governments, community leaders and planners, and residents to urgently develop a vision for adapting to, and preparing for, a changing environment.

Resilience in the face of extreme heat

The impacts of extreme heat can threaten urban infrastructure that was not built to withstand such extreme weather events. Just as we created these conditions, we also have the opportunity to create environments that protect communities from the dangers of climate change and extreme heat.

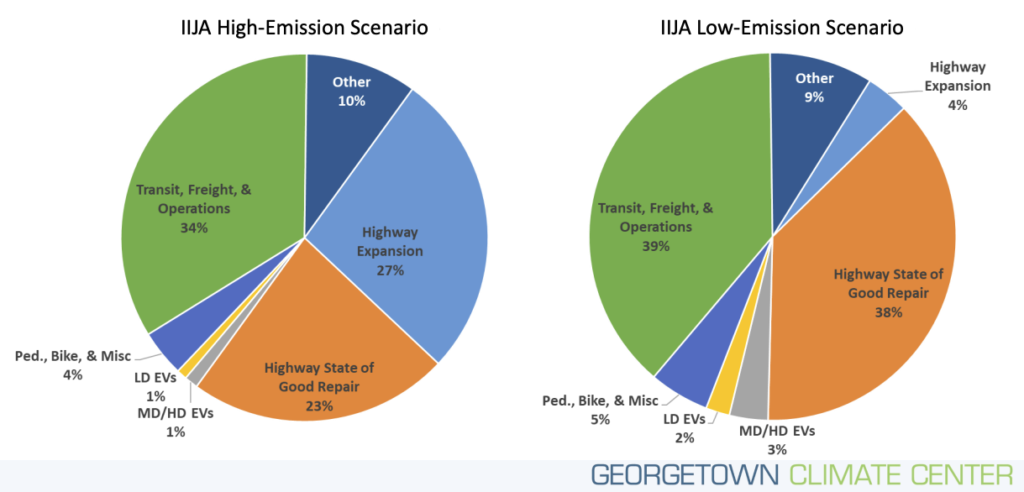

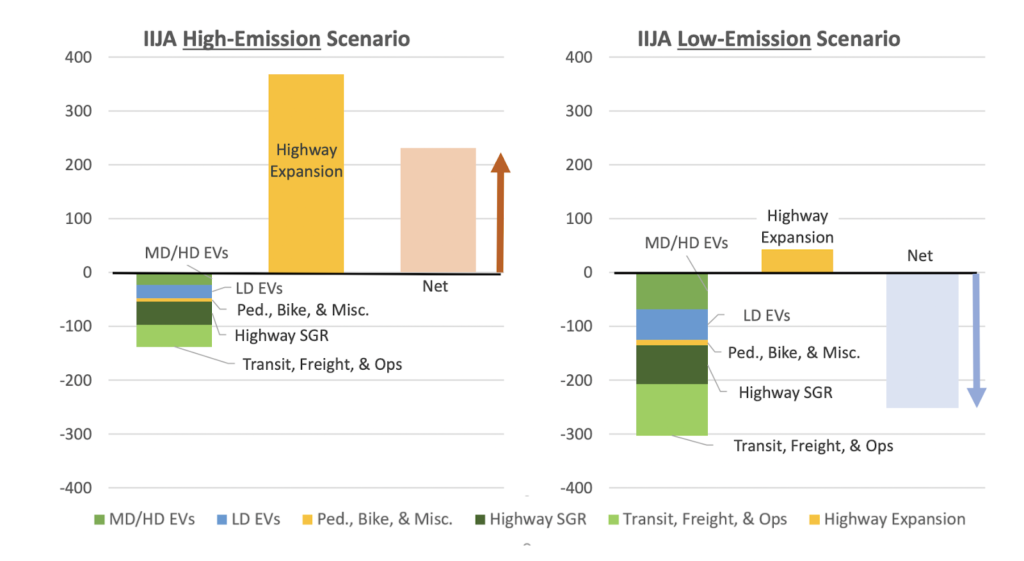

With transportation policies and investments encouraging highways and sprawling development, communities have to drive further away to access the jobs and services they need to get to, causing more emissions to be generated. In combating extreme heat, a necessary strategy is measuring and reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and vehicle miles traveled (VMT) within the transportation sector is one way to help combat the impacts of extreme heat. With transportation policies and investments encouraging highways and sprawling development, communities have to drive further away to access the jobs and services they need to get to, causing more emissions to be generated. Tackling car-oriented design can play a significant role in not only reducing emissions but also mitigating the negative outcomes associated with extreme heat.

Other ways that we can address extreme heat in urbanized areas are heat mitigation and heat management. Heat mitigation seeks to reduce heat in our cities by changing the design of built environments. These initiatives might include incorporating more tree shade and native vegetation or using different building materials like more permeable and reflective pavements.

Heat management protects those in our communities when extreme heat can not be avoided. Management strategies could include improving bus shelters, establishing cooling centers, and creating heat preparedness plans. Approaching heat management with smart growth policies—like prioritizing location-efficiency, improving conventional zoning and land-use regulations, and adapting existing infrastructure—can drastically enhance effective response capabilities.

Additionally, our federal government should direct current and future investments toward building more resilient infrastructure. When government agencies, such as the Federal Highway Administration, set standards for materials used in new builds to be greener and better able to withstand high temperatures, they will ensure that taxpayer dollars are used to build a future that is sustainable and livable for all of the nation’s residents.

Solutions to the extreme heat crisis require bipartisan support to ensure that protections are enshrined in legislation and our built environments’ standards. Urbanized areas need to improve their resilience to extreme heat, especially our transportation system, to help ensure residents can safely travel to where they need to go, regardless of the temperature.

a few of which are summarized below:

a few of which are summarized below: