A month has passed since the $1.2 trillion infrastructure deal was signed into law and set the direction for the federal transportation program for the next five years. With this mammoth infusion of unexpected cash (which is already flowing out the door), there is much to unpack as to exactly how much money there is for the surface transportation program and how it can be used.

To big fanfare, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act was signed into law on November 15, 2021 by President Biden. The President and the press have touted how this law will invest $550 billions in supplemental appropriations into transportation and other infrastructure needs of the United States. But rather than just how much more the pie was supersized, most states, regions, and local governments want to know more details about the size of all the bill’s various pie pieces. T4America has you covered, dissecting the infrastructure law and following the money for the surface transportation program.

FHWA also released their full apportionment tables on Dec. 15, which show the full official breakdown of where the money is going and what sources it’s coming from. Find those tables here.

This post is part of T4America’s suite of materials explaining the 2021 $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), which governs all federal transportation policy and funding through 2026. What do you need to know about the new infrastructure law? We know that federal transportation policy can be intimidating and confusing. Our hub for the new law will walk you through it, from the basics all the way to more complex details.

1) Where this money is going—the big picture

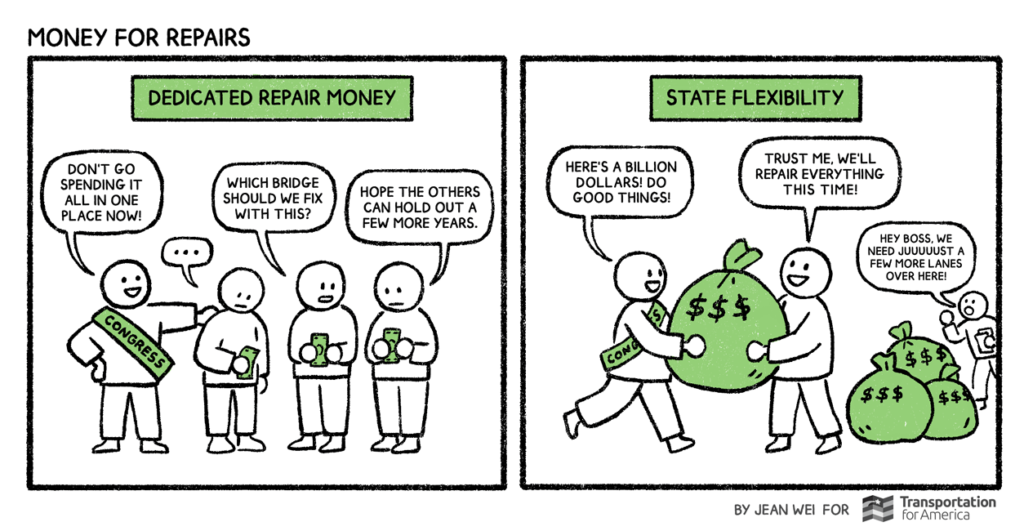

As the following chart shows, 54 percent ($643 billion) of the infrastructure law’s funding goes toward reauthorizing the surface transportation program through 2026. The rest of the bill’s $1.2 trillion price tag goes toward other various non surface-transportation infrastructure. This $643 billion part of the deal has been reported as reauthorization plus additional above-and-beyond funds for various programs (even by us!), but the easiest way to understand this is that this is a massive five-year authorization that’s nearly twice the size of the FAST Act that it replaces. (The next biggest question is how much of the $643 billion comes from the gas-tax-funded trust fund, and how much comes from general tax dollars, which we get into in #2 below.)

Of this $643 billion, two-thirds of the money ($432 billion) is flowing to conventional highway programs.

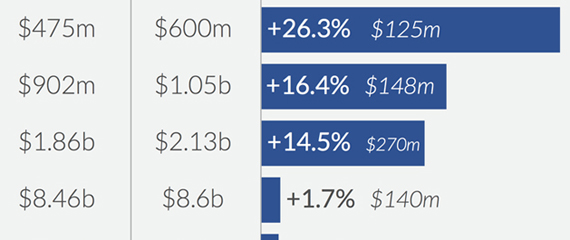

Just to put this scale of spending in perspective, if the FAST Act (the just-ended five-year transportation law) had just been extended instead, that would have only been about $299 billion for these three basic areas of funding over five years. So compared to the previous five-year law, the new infrastructure bill brings a:

- 90 percent increase in highway program funding (from $226 up to $432 billion);

- 79 percent increase in public transportation funding (from $61 billion up to $109 billion); and

- 750 percent increase in railroad infrastructure funding (from $12 billion up to $102 billion)

While the bill has added some new programs (some of which we cover here), the primary way to understand the amount of money is that it will go down as roughly double what we spent over the previous five years.

2) Where is this money coming from?

Taking a closer look at that nearly $432 billion for highways, $110+ billion in supplemental funding (for predominantly highway competitive grant programs) is sourced from general funds from the US Treasury, i.e, paid for with tax dollars from every American and not just gas taxes In a notable change from historic practice, these supplemental funds will be appropriated in advance of other priorities in the annual budget process. (Typically, funding for programs that are not funded with gas tax dollars are fought over year after year in appropriations, though the starting point may be the “authorized” amount in the current five-year authorization.) This is different from a couple of discretionary programs, such as the Healthy Streets program, which authorizes expenditures, but did not identify funding for the program. These types of programs will face potential cuts before competitive highway programs ever do, for example.

This supplemental funding from all taxpayers is layered on about $312 billion sourced from the gas-tax-funded Highway Trust Fund (HTF). 87 percent (about $271 billion) of those trust fund dollars is directed to formula programs and will be spent at the discretion of states and metro areas (within the contours of the policy Congress wrote.) The administration has almost no ability to shape how those dollars get spent with future administrative actions or rulemakings. In fact, this money is already flowing directly into the coffers of state departments of transportation. The rest of the $312B in trust fund dollars (~$39B) are being directed to discretionary programs, such as competitive grants and research administered by USDOT.

When it comes to the federal transit program, the infrastructure law sets aside $109 billion, of which nearly $70 billion is from the also gas-tax-funded Mass Transit Account within the HTF, and an additional $39 billion in general tax funds over the next five years (which will also be appropriated each year in advance of other budget needs.)

Lastly, the federal rail program sets aside $102 billion over five years to be annually appropriated in advance of other budget needs, from the general fund from the US Treasury. None of the rail funding comes from the Highway Trust Fund.

As far as how these “advance” appropriations are going to work out in practice, no one is really sure what to expect in reality over the next five years as Congress could change several times over during the 2021 infrastructure law’s lifespan. In theory, these programs provided with appropriations in advance (like transit and passenger rail) should be safer than other programs that are wholly discretionary and left up to future appropriators to decide funding each year, but it’s a real possibility that a new Congress could certainly find a way to undo some of the advance funding for programs that they deem unworthy. This will be an issue that we will be keeping a close eye on in the years ahead.

3) What makes the infrastructure law’s funding historic?

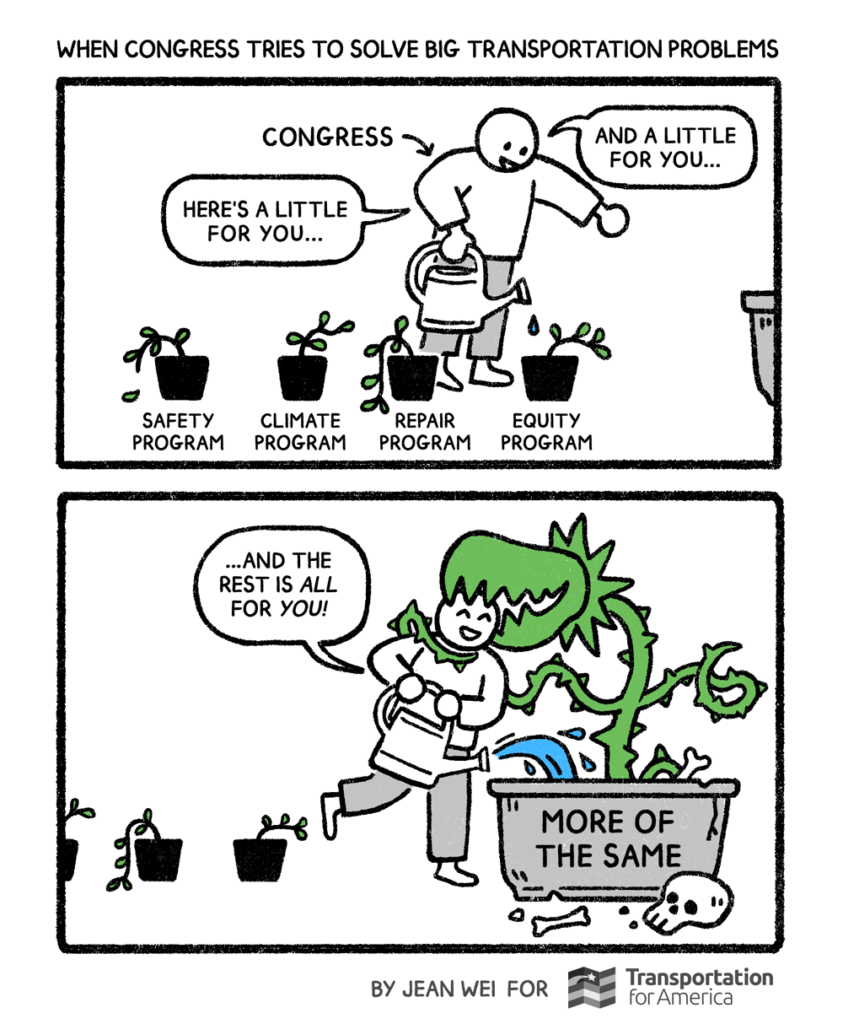

The infrastructure law comes with its flaws in policy, but there are still opportunities to maximize the potential of this unprecedented influx of transportation investment. As noted in the first graphic above, these are huge increases in funding over what states and metro areas and transit agencies would have expected to see in just another year of the FAST Act.

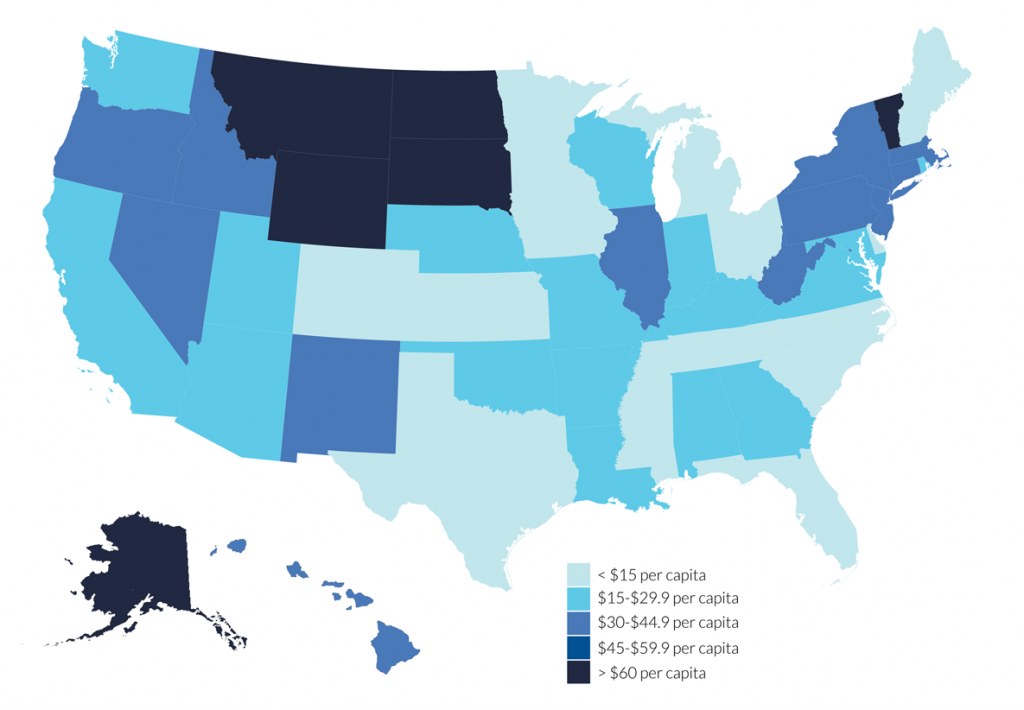

The vast majority of that highway money will be allocated to the states using complex formulas that ensure an equitable distribution of funding tied to average gas tax receipts and previous state allocations. Based on what T4America knows on the apportionment formula, the following chart highlights how the total highway funding for formula programs can be sliced and diced to the states. Of all the states, Texas, California, and Florida account for a quarter of the apportionment of the federal highway program. It will be incumbent on USDOT and advocates to hold all of the states accountable for how their federal dollars are used.