High gas prices put pressure on many Americans’ finances. Unfortunately, the cost of gas depends on a variety of factors, and there’s no silver bullet. Focusing on ineffective short-term solutions can often distract from the long-term problem: when the places we live are designed only for car travel (and longer trips), Americans are forced to pay the cost.

Gas prices have been rising throughout the year, nearing an all-time inflation-adjusted US high. Millions of Americans who rely on a vehicle for essential trips also may depend on low gas prices to make ends meet. Under pressure, state and federal legislators are trying to find ways to drive down the price, including passing gas tax holidays and proposing a federal price gouging bill. However, a variety of factors influence gas prices, and these legislative efforts have little chance of stemming the tide. Gas tax holidays are a particularly shortsighted choice. They threaten funding for needed infrastructure projects, many of which could ultimately alleviate pain at the pump.

Electric vehicles can’t be the sole answer to this problem either, because the issues that come up when people have to drive everywhere, even for the shortest trips, aren’t limited to the cost of fuel. All that driving takes up valuable time. Cars take up space on the road, which turns into traffic, making travel last even longer. It’s expensive to purchase and maintain a car, and when people have to own cars to travel, those who can’t afford one or are unable to drive one are left stranded. (We wrote about some of these issues in our report Driving Down Emissions.)

Regardless of the cost of gas, it’s never been cheap or convenient to rely solely on driving for daily travel. Whether electric or gas-powered, cars are expensive, and Americans have to drive them further than ever just to access their daily needs—Americans in the biggest metro areas are driving 20 percent more per day than three decades ago.

While gas tax holidays will fail to provide significant relief (and cut revenues for roads and bridges in the process), there are enough other organizations and economists and elected leaders trying to figure out short-term solutions for these historically high prices. We’re taking the long view.

Last year’s infrastructure law, a historic investment in our nation’s transportation system, could provide longer lasting solutions for struggling travelers who need to save time and money at the pump.

The infrastructure law made new funds available to improve transit speeds and access, reconnect communities separated by dangerous infrastructure, and design safer and more active streets. We’ve written before about how these changes can enhance equity and improve climate outcomes, but there’s another benefit we might not bring up enough: more options mean more ways for travelers to save on transportation.

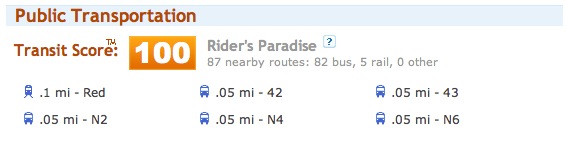

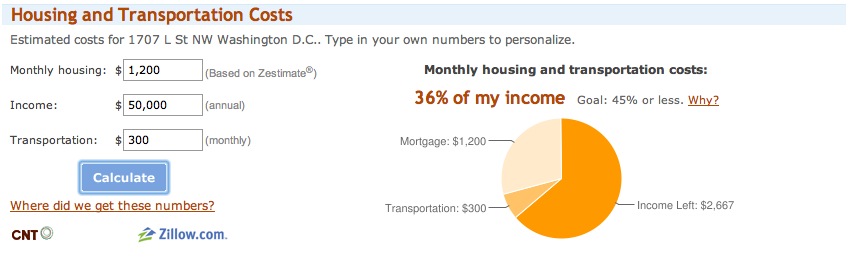

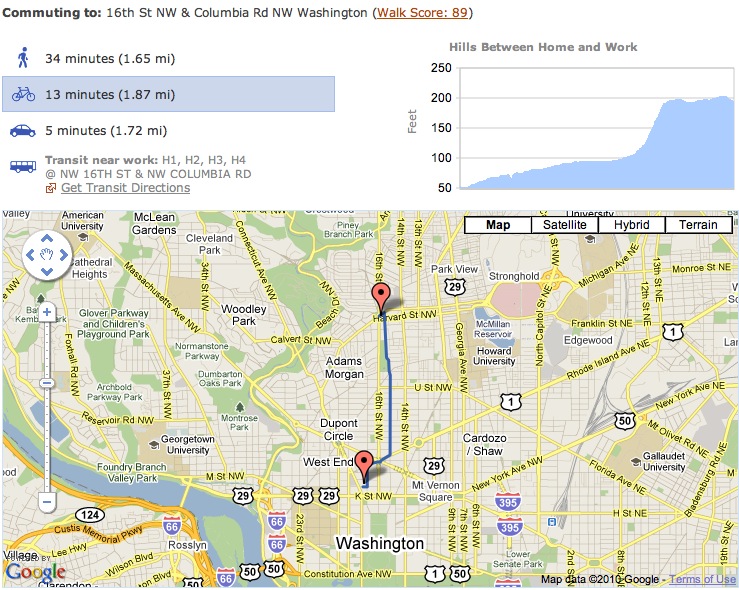

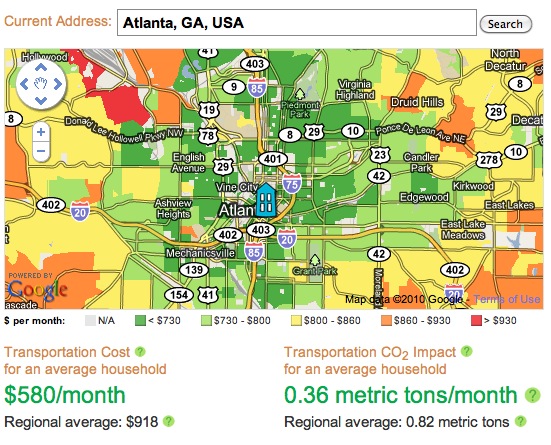

When people live in walkable, multimodal places (of nearly any size) where destinations are located closer together, they can walk, roll, or take the bus to get to work, school, and the grocery store. As gas prices rose, people in these sorts of places, whether affluent or lower-income, were fortunate enough to be able to take much shorter trips by car or switch to other modes of travel. In doing so, they avoided some of the rising cost of car travel, even if they occasionally drove.

After 2008, the last time gas prices rose, we had a similar opportunity to make lasting changes to our infrastructure. Demand rose for alternative modes of travel, especially in areas that already had long-established alternate options. If we had invested in multimodal transportation, we’d be in a very different situation today. But we didn’t—and this is where we ended up.

Because much of the funding in the infrastructure law is flexible, we can use it to give travelers more choices. Or we can further entrench ourselves in a system that requires more driving, more pollution, and more unexpected costs. Those choices will be up to states and metro areas as they decide how to invest these funds.

To really address the climbing cost of car travel, state DOTs and metro areas need to make sound infrastructure investments. If they merely use the infrastructure law to supercharge their existing work to prioritize speedy, long-distance travel at the expense of shorter trips via a range of modes, we’ll be right back in this mess the next time gas prices rise. When that time comes, we’ll know who deserves at least some of the blame.