The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) is rolling out billions in funding for high-powered electric vehicle chargers along highways, but the main beneficiary of these funds has been gas stations—meaning we’re missing out on prime opportunities to support other local businesses. A new bill introduced to Congress last week could enable electrification funds to drive economic development opportunities in small towns.

Across the country, states have begun the rollout of the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program. NEVI is designed to eliminate anxiety over EV range by supporting longer trips with an interstate-centered network of EV chargers.

Under this $5 billion federal program, states have been tasked with deploying high-powered EV fast-charging sites, eventually accommodating all Americans with public charging opportunities at least once every 50 miles along designated highways. Over 500 new high-power electric vehicle charging sites have been announced so far (with sites being announced at an accelerating pace), and the IIJA is beginning to deliver on its promise to bring unprecedented support for electric vehicles.

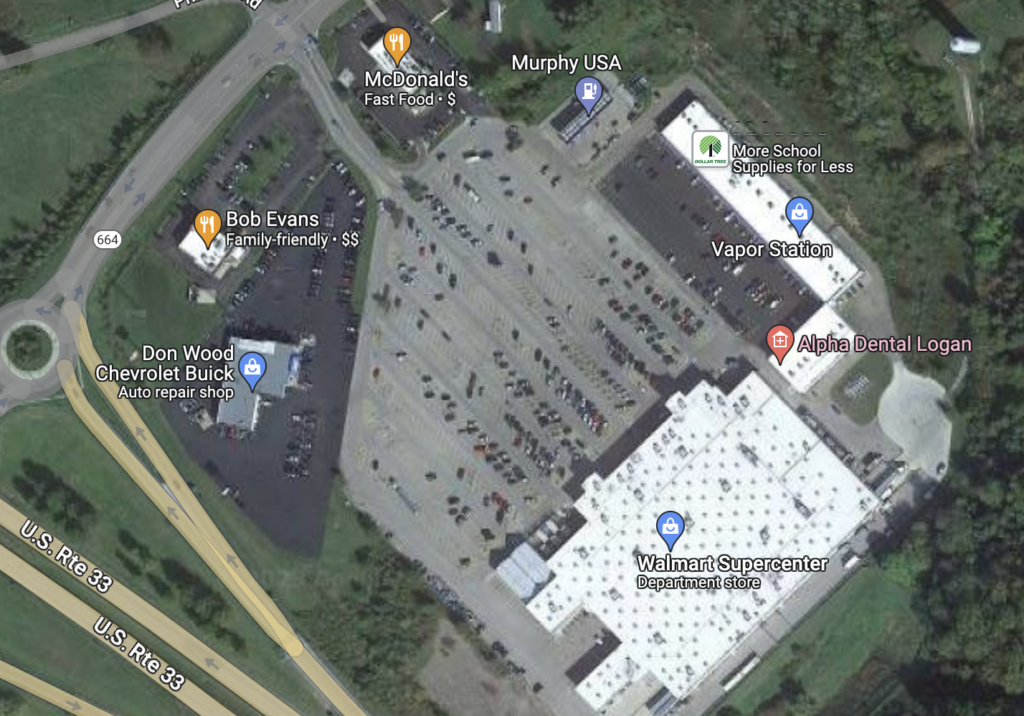

As we explained in our first blog on NEVI, FHWA-issued guidance requiring states to plan their NEVI charger sites within one mile of designated highway exits has strongly influenced the types of sites that receive federal funding. This leaves only a narrow band of land eligible for NEVI funding, restricting the potentially transformative impact that the $5 billion program could achieve, especially for rural communities.

Under the one-mile guidance, states’ programs have shown heavy biases towards awarding hundreds of millions in funds to gas stations and truck stops—in fact, these locations make up about 70 percent of all awards so far. While the IIJA called for NEVI to consider existing fuel retailers, the law also called for the program to prioritize small businesses.

When fully built out, the national network of NEVI-funded public chargers will extend through hundreds of miles of rural areas. While a rural town’s borders’ could stretch up to a highway, it is often the case that the core of communities, where federal investments could make the biggest impact, are close, but down a road less traveled compared to major interstates, too far away to receive federal funding under NEVI. This means that many rural towns, located slightly more than a mile from an interstate, could be missing out on federal transportation electrification funds, even if it could represent a major opportunity to support local business and enhance the traveler experience with more service options while waiting for the vehicle to charge.

Win-win-win strategies for the EV transition

Thankfully, Congress is now making an effort to seize this opportunity, with the recent introduction of Representative Trone’s RECHARGE EV Act (which stands for Revitalizing Economic Competitiveness of Highway Adjacent Areas with Reliable Green Energy for Electric Vehicles—because Congress loves acronyms). Instead of only allowing exceptions to the NEVI program’s one-mile rule for technical reasons, the bill would allow states to turn electrification into even more of a win-win-win: a boost for small-town local businesses and their customers, greater distribution of benefits to rural communities, and increased flexibility for NEVI deployment.

Small business boosts

To understand the value of local EV charging stations, keep in mind that NEVI-funded Level 3 Direct Current Fast Chargers can take between 20 minutes to an hour to recharge a depleted EV. That’s time that vehicle owners could be spending sight-seeing and popping into nearby shops.

A recent study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that EV charging stations boost spending at nearby businesses, an effect we described previously as Charger Oriented Development. According to their research, businesses with EV chargers within walking distance received thousands of dollars more revenue annually, and the effect was even greater in disadvantaged communities. Instead of gas stations, siting NEVI chargers in rural towns could provide an economic boost to small businesses, rural towns, and historically disadvantaged communities, if guided by a smart growth lens. As an added bonus, the increased access to varied amenities could enhance the traveler experience and provide opportunities to get needed items and services at one stop, potentially reducing overall miles traveled.

Equitable electric upgrades in a constrained supply chain

Beyond the Level 3 EV chargers themselves, NEVI funding helps subsidize the electric infrastructure work required to get those stations powered up and running, such as installing transformers, or wiring to chargers. A major hang-up for swift deployment of the NEVI program today (and likely in all types of future electrification programs) is a national shortage of electrical equipment and infrastructure. This shortage leads to long waitlists for key electrical components necessary to install before powering up EV charging stations.

One way to stretch these vital resources is to deploy new electric infrastructure in ways that benefit the most people in a given community. While upgrades at remote gas stations could enable charging at just one lot, installations centered on small towns could help jumpstart a community’s access to future electrification opportunities they might otherwise miss out on.

Increased flexibility and options to build towards national goals

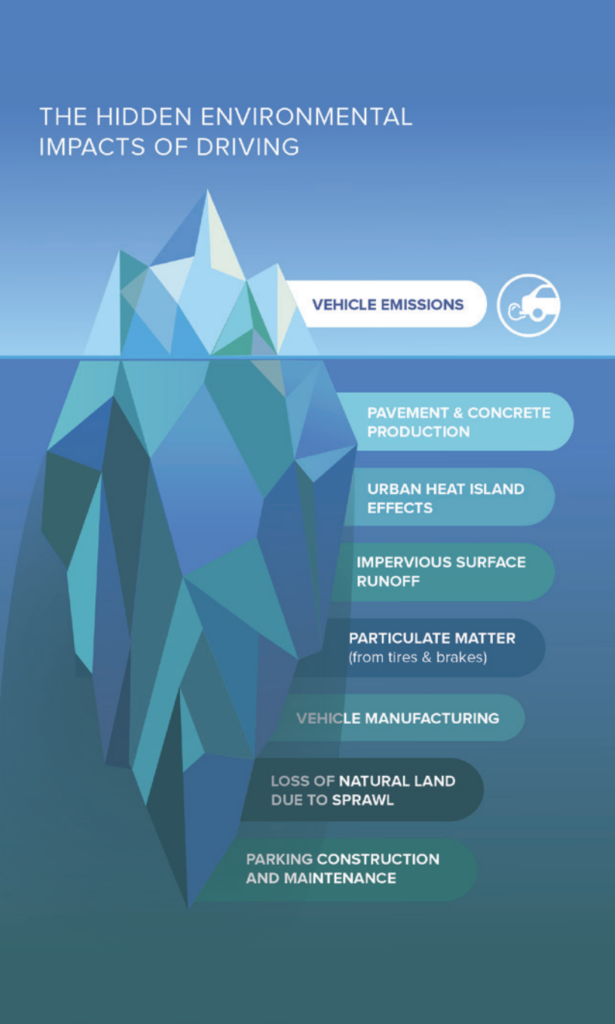

We need both transportation electrification and more opportunities to travel outside of a car in order to achieve emissions reduction that averts the worst consequences of climate change. The RECHARGE EV Act would give states greater flexibility and discretion to pursue electrification in ways that more efficiently distribute benefits to communities. Besides adding to the national network, placing these chargers in communities can show how rural stakeholders that they, too, can participate in the electrification transition.

The RECHARGE EV Act is a small but meaningful step towards more inclusive and effective EV infrastructure that prioritizes rural small businesses and the experience of everyday travelers. While NEVI is part of our essential efforts to reduce transportation emissions through electrification, the program still has a long way to go to maximize its potential. By thinking beyond the one-mile rule, this legislation not only enhances national access to electric vehicle charging but also stimulates local economies and fosters greater access to EV charging and future electrified opportunities.