Workforce recruitment and retention issues that plagued the transportation industry long before the pandemic now threaten the industry’s ability to implement and get the most out of the 2021 infrastructure bill. Though there are workforce development programs in the infrastructure bill, the administration still needs to take action to make these programs a reality.

This post is part of T4America’s suite of materials explaining the 2021 $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), which governs all federal transportation policy and funding through 2026. What do you need to know about the new infrastructure law? We know that federal transportation policy can be intimidating and confusing. Our hub for the new law will walk you through it, from the basics all the way to more complex details.

In every sector of the transportation industry, whether the graying workforce is resulting in high levels of retirement or workers are resigning due to stress caused by the pandemic, transportation workers are leaving large numbers of vacancies that can’t be filled fast enough.

Filling the growing number of vacancies is no easy task. A lack of awareness of the transportation sector coupled with a lack of vocational training for a diversity of transportation needed skills makes qualified applicants hard to find and attract. An overly burdensome hiring process means that hiring can take months, and sometimes qualified applicants are kept from moving forward due to many layers of applicant review for federal employees.

There are other recruitment and retainment issues. Wages aren’t keeping up with the private sector. Rural areas and communities with the least amount of resources struggle to pull in qualified applicants and keep them long-term, especially when they have to compete with neighboring communities for finite talent.

There’s a shortage of good jobs in the transportation industry. Stagnant growth potential, inflexible and unsafe work conditions, and a lack of leadership development already made it difficult for the industry to maintain a strong workforce. When the pandemic came along, it only exacerbated these retainment issues.

Without knowledge retention systems in place, the loss isn’t just about workers; it’s about institutional industry knowledge that isn’t easily replaced. After the long, arduous process of recruiting and hiring, even more time passes before new hires are operating at an equal level to the staff they’ve replaced. Unless the transportation industry invests properly in its workforce, they’ll be unable to use the full potential of the infrastructure bill to benefit communities.

What’s in the law?

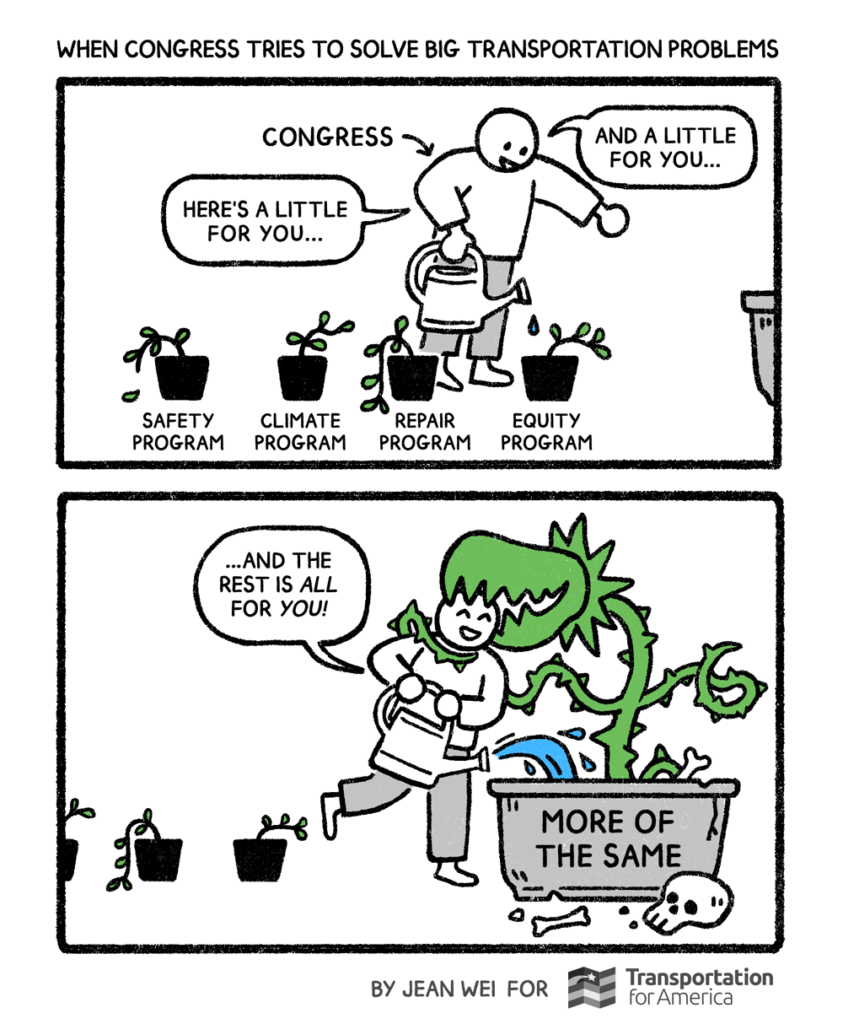

The core highway formula programs (NHPP, CMAQ, STBG, and HSIP) allow their funds to be used for workforce development programs. This includes tuition and educational expenses, employee professional development, student internships, apprenticeships, college support, educational outreach activities, and more. States are free to use their existing funds to beef up these efforts

Overall, the federal government is aware of the need to develop the transportation workforce, which is why the infrastructure bill encourages states to create human capital plans, but these plans aren’t required and there’s no funding available to implement the plans once they’re created. Not surprisingly, without an incentive, few states take the federal government’s advice.

The major source of workforce development funds will come from the five percent set-aside for workforce development training related to zero emission vehicles. Specifically the funds can be used to fund workforce development training, including apprenticeships and other labor-management training programs as recipients make the transition to zero emission vehicles.

The infrastructure bill also includes some other workforce development programs, but there’s no dedicated funding for these programs, and most programs have no specific funding item at all, meaning the Secretary of Transportation, Pete Buttigieg, will need to carry out these programs using administrative funds.

Below are programs created by the infrastructure bill with no dedicated funding.

- To improve awareness of the transportation sector and help with recruitment problems, Secretary Buttigieg must create a motor carrier driver apprenticeship program for people under the age of 21. The pilot program would include 3,000 apprentices and last three years.

- To help diversify the transportation workforce, the federal motor carrier safety administrator has to create an advisory board to educate, mentor, and train women in the trucking industry.

- Secretary Buttigieg needs to create an agreement with the National Academy of Sciences to carry out a workforce needs assessment.

- To develop a transportation technologies and systems industry workforce development implementation plan, Secretary Buttigieg must establish a working group made up of the Secretary of Energy, Secretary of Labor, and other federal agency heads.

With no more than $5 million per year, Secretary Buttigieg is also asked to establish a transportation workforce outreach program to increase awareness of transportation career opportunities especially for diverse populations.

How else could the administration improve workforce development?

Clearly, the administration has a lot of work to do to develop the transportation workforce to realize the full benefit of this historic investment in infrastructure. In the grand scheme of implementation, it might feel easy to overlook workforce development needs, but without human capital, on-the-ground change will be difficult, in some cases even impossible, to achieve.

The Build Back Better Act (BBBA), on ice in Congress, included $20 billion to help build that national workforce. Though not targeted at transportation, these programs, which included expanding apprenticeships and investing in increased enforcement of labor law and civil rights violations to help diversify the workforce, would have undoubtedly helped the transportation industry. Though the BBBA is unlikely to pass as a whole, it’s possible that Congress could still pass this provision, and the administration should encourage them to do so.

How can these programs help achieve our goals?

Equity

There are clear equity implications for ignoring workforce development concerns. In failing to invest in the transportation workforce, the administration will perpetuate existing equity concerns across the professional sphere. Plus, without a strong, well-supported, diverse workforce with staff that reflects the communities they serve, it will be even harder to find equitable solutions to today’s transportation problems. In the end, communities with the least resources will suffer most if we fail to increase their capacity.

So what?

The infrastructure law sets up several avenues to support and develop the transportation workforce, but these programs are underfunded and place the onus on states to take initiative. They will stay that way without administrative action. Advocates can and should work with their local governments to make sure these programs are created at the local level. They can also push their federal representatives to pass additional funding for workforce development.

Note: There are ample opportunities for the infrastructure law to support good projects and better outcomes. We also produced memos to explain the available federal programs for funding various types of projects. Read our memo about available funding opportunities for workforce development.