San Juan, PR: Trampling communities and a national rainforest in the name of “economic progress”

Deemed a project of major economic significance for several decades by the Puerto Rico’s Department of Transportation (DTOP), the agency rammed through community opposition, environmental review processes, and legal battles to construct PR-66, a limited access tollway that is benefitting few and scarring communities and their environs.

History and context

As its historically rural population rapidly urbanizes, Puerto Rico has been iterating ways to stimulate and diversify its economy and facilitate speedy travel. Because of its status as a US territory, Puerto Rico’s transportation policy and investment strategy has been molded by an auto-centric lens pushed by both Washington and private sector investors filling transportation funding gaps for decades. However, federal transportation investment in Puerto Rico has been scant. (For example, in fiscal year 2022, Puerto Rico received $173 million in federal funding from the 2021 infrastructure law. Compare that to Utah, with the same population receiving $460 million or Connecticut, with slightly larger land area receiving $665 million.) Because of limited transportation funding, Puerto Rico has had to rely on private sector investment, which prioritizes roads with tolls over transit.

In the 1960s, inspired by the Eisenhower Interstate Plan, Puerto Rico created its Highway Development Plan with the goal of creating high speed roadway connectivity of the various island communities to San Juan. From this plan, all but one of those highways were built by the 1990s. The highway yet to be built would prove to be the most hotly contested.

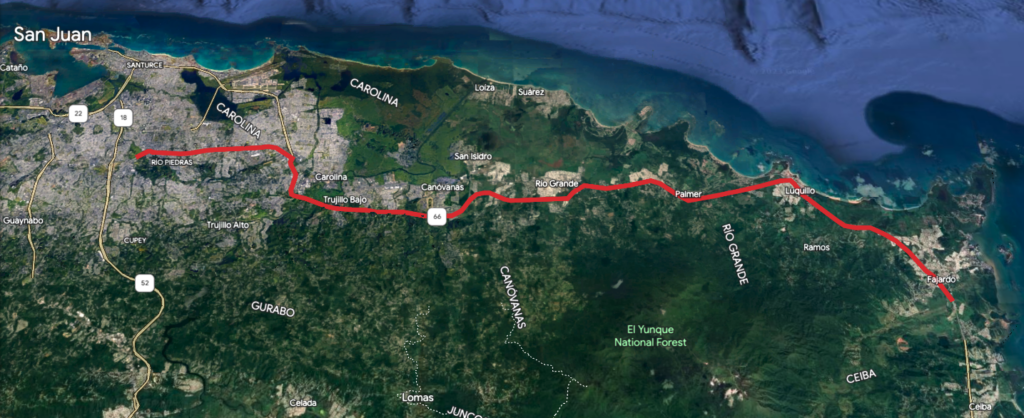

PR-66, as envisioned by the Puerto Rico Department of Transportation and Public Works (DTOP by its Spanish acronym), connects PR-1 (the historic route between San Juan and Ponce) and PR-52 (an expressway parallel to PR-1) to PR-3 (the historic route that connects the eastern island communities to San Juan) and the PR-53 northeastern terminus.

A hard-won battle over federal regulations

Development of this 31-mile 4-lane tollway corridor started in 1992, when the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process began. This process required the DTOP to assess environmental considerations, such as noise, water, air pollution, stormwater runoff and erosion, impact to historical resources as well as community displacement.

DTOP justified the route by arguing it would reduce congestion (reducing travel time from Fajardo to San Juan by 30-40 minutes each way), increase travel time reliability for vehicles, and stimulate economic growth and job creation in the corridor.

Communities along the proposed corridor were caught off guard as the NEPA process got underway. A sole public meeting on project impacts was held two days before New Years Eve 1992, providing little to no information to the community, soliciting minimal feedback, and yielding a questionable Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). In May 1993, the Environmental Quality Board (JCA in its Spanish acronym) provided preliminary feedback on the EIS, stating that the EIS was only analyzing economic impacts and failing to assess other critical aspects of the NEPA process which include displacement, environmental degradation (like runoff, erosion, and noise), and never exploring alternative solutions to achieve the project’s purpose and need. Additionally, the JCA questioned DTOP’s vague analysis, as well as its statements on where and what it intended to build in the corridor. Despite some procedural setbacks, DTOP proceeded to develop the project and move to finalize the EIS. By the mid 1990s, DTOP began to seize homes and businesses via eminent domain to clear the way for road’s construction.

A local resident, Wanda Colón Cortés, was outraged with how DTOP was skirting the NEPA process, and she created a group of community members called the Communities Opposed to Route 66 to oppose the project. The demands from Communities Opposed to Route 66 were crystal clear: stop any construction and thoroughly evaluate the corridor for a broad array of alternatives and their impacts as required by NEPA. They reasoned with DTOP and JCA that they agree with the purpose and need of the project, but want to ensure a fair, thorough, transparent process.

Rather than address the community’s comments, DTOP amended the EIS in February 1996 to shorten the corridor, and JCA declared this EIS adequate in May 1997. In 1997, arguing that the EIS determination was premature, Communities Opposed to Route 66 took both DTOP and JCA to court. The case would be interfered with by the Puerto Rico legislature, and go all the way to the Puerto Rico Supreme Court by 1999. The community group declared victory in April 2000, when the Puerto Rico Supreme Court issued its ruling, determining that:

- The legislature’s involvement violated separations of powers and deemed their actions unconstitutional,

- JCA could not be edited out of the environmental review process as DTOP and the legislature attempted, and

- The NEPA process needs to be thoroughly followed for the full proposed corridor, not just its segments.

A highway slowed but never stopped

After DTOP was defeated in court, it went back to the drawing board and prepared a new EIS draft in late 2001, focused exclusively on a 13-mile segment of the original corridor (now Canovanas to Carolina). When presented with this proposal, the community again expressed discomfort over environmental impact and community displacement. So DTOP tried again, and in 2002, they prepared an EIS that placed the corridor further away from the existing community—encroaching into the El Yunque National Rainforest instead. Because this proposal impacted fewer community members, community opposition dwindled. DTOP was then able to finalize the EIS in late 2002, with construction of the corridor starting by summer 2003.

The PR-66 toll corridor would fully open in October 2012 under a 50-year public-private partnership agreement, but it was not without other issues along the way. On multiple occasions, the project required additional funding to continue and complete construction, with $160 million for seizing other properties along the corridor. In late 2006, the Northeast Ecological Corridor Coalition blasted DTOP in an op-ed for El Nuevo Dia (the island’s main newspaper) for not doing enough to mitigate environmental harm and failing to follow through on its promises in the EIS.

That coalition also emphasized that the JCA needs to fulfill its role in reviewing and providing oversight on DTOP’s environmental mitigation, especially on stormwater runoff, erosion, noise and air pollution, water quality, and deforestation. This sentiment was shared by Fanny Peña Roque, a community advocate, who called out DTOP for not mitigating community access to jobs and services for their cut off mountainside community to facilitate speeding up construction. Her community remained cut off for months, even after the highway project was completed.

The coalition also tried to raise the alarm on the impact PR-66 has and will continue to have on incentivizing new suburban sprawl and the incongruent development across communities within the corridor (with even some new developments caught in the crosshairs of the corridor for seizure after recently being approved and/or built). But these calls never gained momentum.

Ten years have passed since the full opening of the PR-66 corridor. Traversing it today traffic volumes are very low (no more than 30k average annual daily traffic volume), roadway fatalities high, erosion and flooding impacts a regular occurrence, and toll rates are very high (at 30 cents per mile, it is the second most expensive roadway in the United States) with deliberations in the past year to increase toll rates to help with the project’s debt service.

Lessons for budding Community Connectors

Understand the regulatory tools at your disposal—and don’t be afraid to use them. As other communities look to challenge divisive transportation infrastructure, it will be important for advocates to be informed about the NEPA process and related regulatory requirements, and hold firm on accountability of those requirements. However, NEPA alone won’t be enough.

Find your message and hold your vision, even as circumstances change. Community advocates fighting the PR-66 project needed to have a vision beyond protecting homes and buildings. Yes the project impacted homes and businesses, but advocates were unable to translate the messaging and sustained attention more broadly when DTOP revised the corridor footprint and continued developing and building the project.

Recognize project alternatives. Advocates should also try to articulate a clear alternative approach to address the project’s purpose. Then Governor Luis Fortuño in a 2011 conference keynote (and under the backdrop of community protests) blasted opponents of the project, stating “Puerto Rico can’t permit the well being and progress of our community to be held hostage by people who think all progress is bad.” To address this issue, community connectors should work with other stakeholders to inclusively formulate an alternative vision/strategy to tackle the aspirations of present and/or proposed divisive transportation infrastructure.

Community Connectors: tools for advocates

You may be fighting against a freeway expansion. You may be trying to advance a Reconnecting Communities project to remove an old highway. You might be just trying to make wide, dangerous arterial roads a little safer for people to cross. This Community Connectors portal explains common terms, decodes the processes, clarifies the important actors, and inspires with helpful real-world stories.

You may be fighting against a freeway expansion. You may be trying to advance a Reconnecting Communities project to remove an old highway. You might be just trying to make wide, dangerous arterial roads a little safer for people to cross. This Community Connectors portal explains common terms, decodes the processes, clarifies the important actors, and inspires with helpful real-world stories.