The Portland City Council is moving forward with a plan to improve transit service through a series of targeted improvements to some of the city’s most delayed bus and streetcar corridors. Known as the Rose Lane Project, it’s designed to advance equity, reduce carbon emissions, and increase transit ridership with quick-build projects. It also offers lessons to other cities struggling with sluggish transits systems mired in a sea of cars.

Yesterday, the City of Roses (Portland, OR) unanimously adopted an ambitious plan to speed up transit service by freeing it from traffic and improve racial equity across the city. Aptly named the Rose Lane Project, the adoption of this plan follows high-profile changes in New York City and San Francisco that have closed entire streets to private vehicles in order to free riders from crippling traffic and open up space for pedestrians and cyclists.

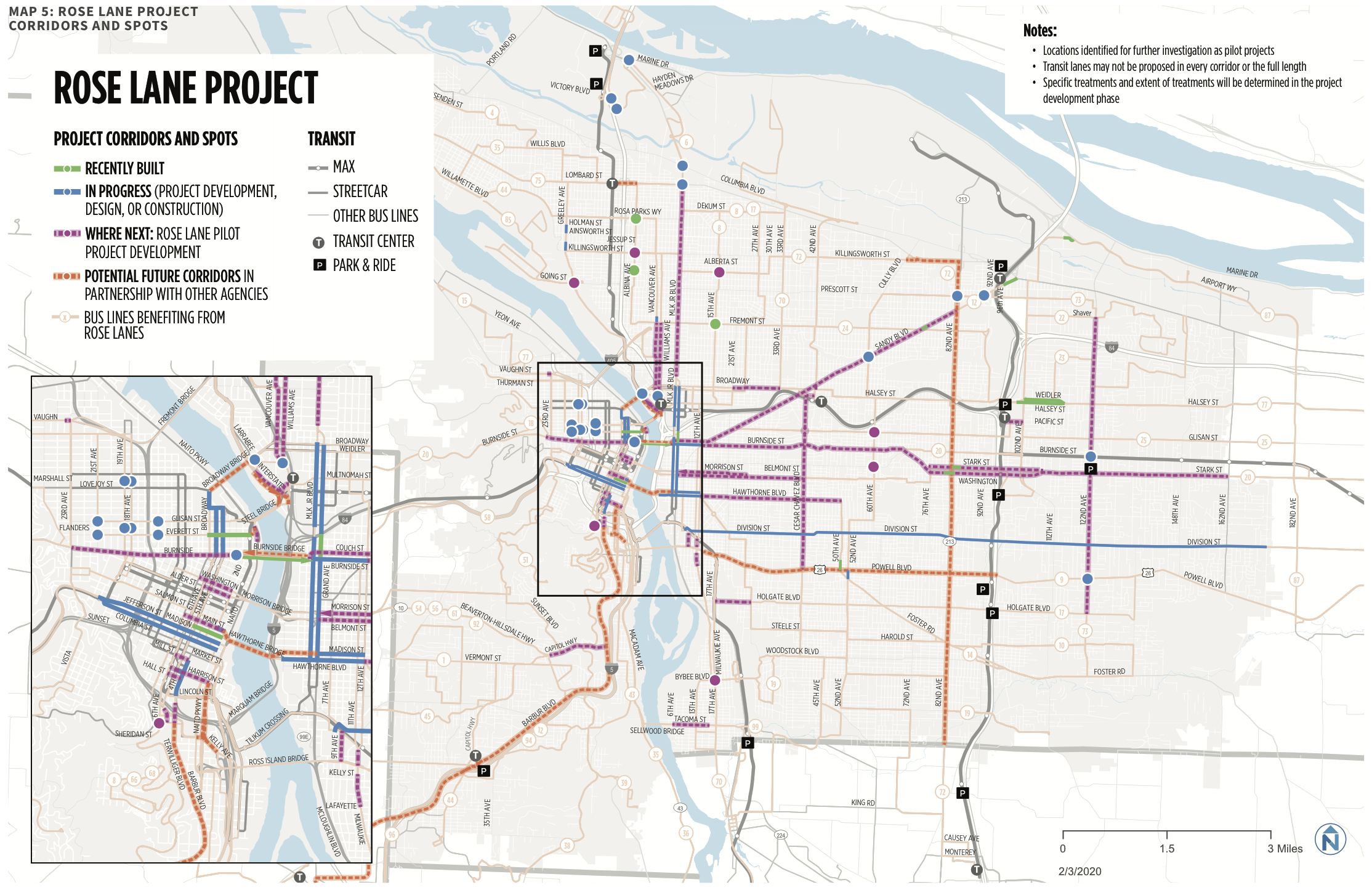

But the Rose Lane project, while sharing similar goals, is different. Instead of closing a single street to vehicles, the city is launching a series of improvements to speed multiple bus lines and streetcars through the city with a variety of treatments, including but not limited to bus lanes. And it’ll all happen fast. The Rose Lane Project is designed to be implemented as pilot projects that can be deployed quickly with low-cost materials, evaluated and tweaked over time, and then made permanent if they’re successful.

Phase 1 consists of 29 separate projects from transit queue jumps to traffic light changes to bus lanes that will be implemented this year and next. Projects in Phase 2 will bring further, tailored street improvements to a network of high-priority transit corridors in 2021 and 2022.

The scale, timeline, and explicit focus on equity and climate change makes the Rose Lane Project unlike anything else being done in the U.S. though it is based in part on the success of Seattle in implementing transit priority and the resulting increase in transit ridership.

The city takes action

In many cities, a transit agency operates the transit system—hiring drivers, collecting fares, maintaining rail lines, etc.—while the city controls the street. A transit agency may request changes to traffic lights, bus stops, or lanes but it’s ultimately up to the city to actually implement those changes on public roadways. This divided responsibility can be a huge obstacle to change; political will, more than money, can become the limiting factor in whether or not transit is truly prioritized on the street. The same truth holds in efforts to dedicate more safe infrastructure for people walking and biking.

In Portland, the unanimous adoption of the Rose Lane Project by the city council sends a clear message: transit is our priority. When fully implemented, the Rose Lane Project will reduce travel times for hundreds of thousands of riders everyday, improve access to jobs and services across the entire city—particularly for low-income households and communities of color—and help the city reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by making transit a more attractive choice to more people. Ultimately the city hopes the Rose Lane Project will help it achieve a goal of 25 percent of trips in the city made by transit.

“The Rose Lane Project demonstrates how equity and climate are interconnected. My office developed this bold, transformative vision for transit with PBOT by centering racial equity—setting a goal to reduce commute times for communities of color—and in doing so we created a powerful tool that will advance our efforts to confront climate change,” said Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) Commissioner Chloe Eudaly. “The Rose Lane Project is a major step toward meeting our equity, climate, and transportation goals by making transit a more viable option for more Portlanders.”

PBOT has put together a full report on the Rose Lane Project that is chock full of easily digestible information and great graphics. Cities around the country should take note—inequality and climate change are issues that every community is dealing with and the Rose Lane Project offers a vision of a healthier, safer, more equitable transportation system.