Is metro Atlanta vote a bellwether for transportation funding?

Flickr photo of Atlanta’s “Spaghetti Junction” by Felicity Green

In my best grandpa voice: Way back in 19 and 96, as a reporter for the Atlanta Journal Constitution, I wrote a series of stories under the heading “Gridshock” that laid out the traffic hell facing metro Atlanta absent something resembling a plan. At the time, the Georgia DOT was wrapping up its $3 billion “Freeing the Freeways” paving bonanza, and the last planned extension of MARTA rapid rail was winding down.

Meanwhile, metro Atlanta was sprawling out of control, spreading out in all directions and in ways that ensured that options other than lengthening car commutes would be hard to provide. At the same time, the metastasizing traffic was far out-pacing the existing and projected highway funding, and the region was facing a collision with the Clean Air Act that would put federal dollars on hold for several years.

Fast forward to 2012. After three tries in the Legislature to win the right to vote on a regional sales tax for transportation and two years of a mandated political process to develop a project list, metro Atlanta voters July 31 finally had a say over a bold transportation spending plan.

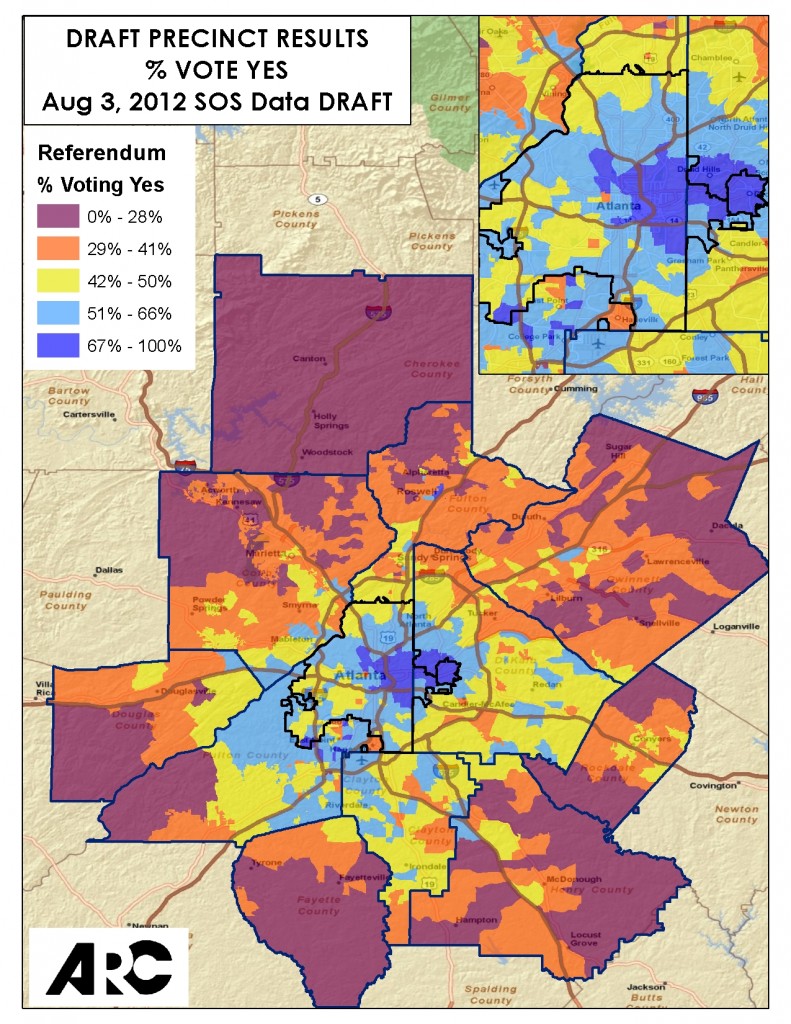

The result: Still no plan. Two-thirds of the voters rejected the Transportation Local Option Sales Tax – or T-SPLOST – which would have put $7.2 billion toward 157 projects throughout the 10-county region, evenly split between highways and transit. It was a serious blow to the Metro Atlanta Chamber of Commerce, whose leaders led the battle to get the right to have a regional vote, and to politician-supporters such as Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed. (His City of Atlanta voters, though, comprised the only jurisdiction to approve the measure.)

But is it a bellwether for transportation votes in other states and metros? The short answer, most likely, is “no”. To be sure, many were following it nationally. The vote came on the heels of MAP-21, a federal bill that seems to presage a shrinking federal role in transportation funding, at least for the near term. Many wondered: Will metro regions and localities be able to make up the gap and bootstrap their way out of congestion and mobility woes?

Like most ballot measures, the Atlanta vote failed for its own peculiar reasons. The Legislature had ensured an uphill battle by mandating the vote be held during the primary election, rather than the November general election. The vast majority of contested races were in Republican districts in the suburbs. The Republican primaries drew an anti-tax electorate to the polls, while residents in the core, who tend to be less tax-averse, had fewer reasons to turn out.

The vote also bore out what we heard in focus groups there last year: Georgia voters are especially negative about their government. Polls and exit interviews showed that many were mistrustful of Georgia DOT on the heels of outrage over the decision to continue tolls on Georgia 400 after the promised sunset. MARTA, too, has been under the cloud of a long fiscal crisis as a result of the economic slump and depressed sales tax revenues.

Many voters also complained of a sense that the project list was a goodie bag for various political interests and not a cohesive plan to address well-articulated needs. The Legislature-mandated process almost assured that outcome. It called for creating a 21-member “regional roundtable” made up of a mayor and county commissioner from each of the region’s ten counties, plus the mayor of Atlanta. While the “pro” campaign pitched the project list as a solution to congestion, the list struck many voters as a collection of pet local projects that did not necessarily add up to a thought-through plan.

Was this an anti-transit — or anti-transit rider — vote? Certainly, some of that sentiment exists. But remember there was plenty of money in this for road building too. As someone who lived in and wrote about the region for many years, I think the other reasons offered here had far more to do with the loss than the public transportation components did. Atlanta is made up of thousands of newer and younger residents who do not carry the baggage of race-based, anti-transit battles of previous decades. Most of them just want a system that works, regardless of mode, and they want efficiency and accountability in their operation.

Are there generalized lessons to be taken from the Atlanta experience? Two important ones:

First, regional votes in places without a tradition of regional institutions and decision-making are an extremely heavy lift. In our focus groups, the idea of a regional solution held a lot of appeal. But in reality, voters were being asked to send a lot of their money to a “regional” approach with unclear lines of accountability. The money would have gone to GDOT, MARTA, the Georgia Regional Transportation Authority and to local jurisdictions throughout 10 counties.

But with money spread all over the place, where did the buck actually stop? They were being asked to trust, not just their local electeds, but government writ large. In this day and time, with this electorate, that may have just been too much to ask.

And second, important though it is, a project list is not necessarily a plan. The Atlanta proponents understood that the 70 percent of transportation tax measures that pass nationwide almost always have a clearly articulated list of promised projects. Given the legislature-mandated process and the resulting list of 157 projects, voters perceived the T-SPLOST as a grab bag of pet projects, offered with a plethora of justifications.

If you can’t sum up the rationale for the plan in a couple of lines, and point to an elected official or body that is ultimately responsible, you are going to have a tough time. Again, our polling and focus group work, as well as lessons gathered from many of our members during ballot fights, bear this out.

So where does this leave metro Atlanta? Two follow-up pieces are worth reading. In one, longtime Atlanta columnist Maria Saporta – a devoted regionalist – suggests it’s time for the core to go it alone. (The piece also includes a very interesting map of the voting results, included below.) And in the other, Georgia Sierra Club President Colleen Kiernan recaps what happened, and suggests the Club’s “strange bedfellows” alliance with the Tea Party may offer a way forward.

Update: Also worth reading is this hopeful editorial in Creative Loafing encouraging those Atlantans that supported the measure to imagine a path forward together, similar to Maria Saporta’s suggestion of the core “going it alone.”

Graphic of the vote by precinct, provided by the Atlanta Regional Commission.

Pingback: Today’s Headlines | Streetsblog Capitol Hill

Pingback: 08.09.12 Your Morning Buzz | Oregon Emerging Local Government Leaders Network