New state and federal leaders will take office in January. Where they stand on transportation will have a significant impact on the future of mobility in America. Here’s how you can engage with your new elected officials to help improve our transportation system in coming years.

The federal government hands states hundreds of millions of dollars on an annual basis, with few strings attached. Governors, state legislators, and local leaders have a great deal of money to deliver the projects, services, and results that voters demand.

Yet the goals of state transportation programs are often misaligned with voter priorities. For example, a recent report from the National Cooperative Highway Research Program showed that by one measure, states use less than four percent of flexible federal dollars on transit, even though they could spend much more. Learn more on TransitCenter’s blog.

Too often, state leaders focus spending on only one result: eliminating congestion. This approach overlooks voter concerns like equity, maintenance, safety, and climate emissions—and by the time decision makers get around to addressing those issues, they’ve spent a great deal of money and time on roadway expansions. (And these expensive new lanes often fill with more traffic, thanks to a process called “induced demand.” We wrote about this costly cycle in our report The Congestion Con.)

We don’t have to settle for more of the same. With new leaders headed into office, advocates have an opportunity to change this old pattern and help create a better transportation system for their community.

New governors can steer the transportation system in the right direction by providing clear instructions on the goals of the state transportation program so that the transportation department can start making progress on those priorities. In addition, governors can choose strong leadership in their own office, the state DOT, and in some cases, the transportation commission that oversees the DOT. The governor should choose leaders that understand the transportation program and are motivated to make needed changes.

Though often overlooked, local leaders, like mayors, might be the most crucial stakeholders in transportation decision-making. When pushes for smart transportation in communities succeed, it’s often due to support from local leaders who lobby for the project on the state and federal level and bring other elected officials to the table.

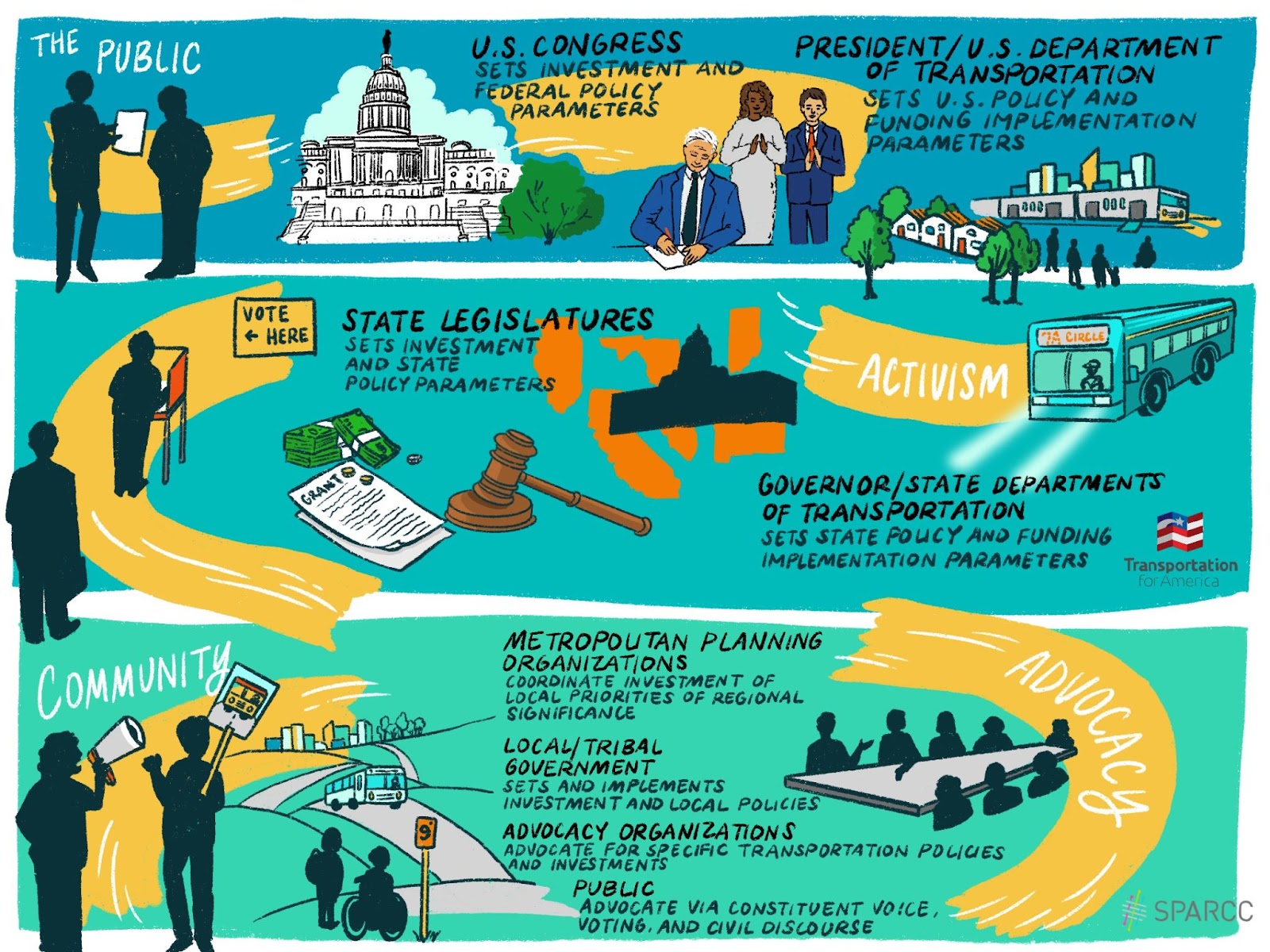

Finally, the federal government still has an important role to play. The authorized funding levels set in the infrastructure law aren’t guaranteed, and we’ve already seen federal policymakers underfund transit and defund certain active transportation programs. The Biden administration also makes the final calls on competitive grant funding, determining which projects will benefit from key funding programs like the Reconnecting Communities Program. By making these decisions, the administration can help ensure federal dollars are advancing the President’s goals, including enhancing equity in the transportation system.

With critical decisions happening at all three levels of government, engaging with new leaders can feel like a daunting task. These three pieces of advice can help you maximize your influence to achieve connected, healthy, equitable communities.

Check in early and often

As their constituent, you have unique power to educate elected officials on the challenges and opportunities that impact the transportation space. State and local leaders will ultimately determine how much funding will go to projects and programs near you, including safety improvements, transit, and highway expansions. Engage with them early to develop an understanding of how and when transportation funding will be used and let them know what your priorities are. Take part in public comment and review periods to encourage them to make the right calls on key policy, investment, and implementation actions.

There are many ways you can reach out to your elected leaders, including joining sign-on letters, engaging with their social media, writing them a letter, calling them up, and even visiting their offices. If they start to move the needle in the right direction, don’t forget to praise them.

Invite your state leaders to join the State Legislator Champions Institute so that they can become effective Complete Streets advocates. Learn more about the Institute here and join an information session on December 6 at 3 p.m. ET.

Find the linchpins

Government decision making happens in phases. Elected officials set their priorities, identify issues and approaches to addressing them, create a plan (including time, resources, and budget parameters), and seek input on their budget, policy, or implementation decisions. Once these steps of the process are complete, they’ll evaluate their progress on their priorities and begin the process again.

When having conversations with elected leaders, seek out information about where they’re at in the process and tailor your asks to the present moment. Find out when public hearings are scheduled and attend them. Get in touch with your local advocacy organizations and follow their lead. Finally, don’t be afraid to point out if important details were missed at an earlier stage of the process (as activist Michael Moritz did in Texas).

T4A members receive regular updates on opportunities for advocacy on the Hill. Learn more about T4A membership here.

Look for common ground

Our transportation needs are frequently touted as bipartisan concerns, and for good reason. The success of our transportation system has a direct impact on every constituent, influencing economic vitality, public health, climate emissions, and everyone’s ability to access the goods and services they need.

Often, elected officials enter office without a clear understanding of how the transportation system can help them reach their goals. By making these connections clear, you can create strong allies, even with leaders who initially disagree with you.

Transportation for America Chair John Robert Smith had just that experience when he brought passenger rail to Meridian, MS—he found that Republican politicians, opposed to passenger rail, were willing to support his project once he explained its economic benefits. To further build support, he humanized the issue by bringing decision makers face to face with constituents to explain how passenger rail impacts them.

The bottom line

It’s not uncommon for federal, state, and local elected leaders to lack a strong understanding of our infrastructure needs. But decision makers at all levels need to know that the transportation program can help them deliver on key issues for their constituents, regardless of their political affiliation. By engaging with your new leaders, you can help them make progress on climate, safety, equity, access, and repair goals.