Despite historic levels of investment in infrastructure over the last twenty years, America’s 2025 infrastructure grades for roads, bridges, safety, and transit look mostly the same. No one should consider putting a single penny more into a program with such bad results. Unfortunately, raising new money is at the top of the list for our country’s association of civil engineers.

The 2025 infrastructure Report Card, released by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) today, grades every aspect of U.S. infrastructure every four years.1 While ASCE has made some notable improvements (we’ll cover some below), they’ve also stuck to their guns: The #1 solution to the poor condition of our roads, bridges, and transit systems is to spend more money. We just aren’t spending enough.

Consider:

- Roads scored a D in 2001 and a D+ in 2025

- Bridges scored a C in 2005 and 2025

Noting that these failing scores happened during a period with a huge infusion of funding in the 2009 stimulus and historic amounts of money for roads in the 2021 infrastructure law, perhaps it’s finally time to stop calling for more money as a potential solution?

There’s an obvious problem with telling taxpayers the price before they tell us what we’re buying. (Especially coming from those employed in building the stuff. ) ASCE has been described by Strong Towns over the years as part of the “Infrastructure Cult”—those who believe that prosperity can always be achieved through more growth, and that any and all infrastructure spending is always a good financial investment that leads to growth. ASCE’s report cards of years past were sometimes comically half-baked when it came to the math: Chuck at Strong Towns examined the numbers in the 2011 report:

…The total cost to households and businesses is $1.042 trillion. Well, ASCE states that to reach “minimum tolerable conditions” (a pretty sad standard) would take an investment of $220 billion annually. Over 10 years, that’s $2.2 trillion. Yeah, you read that right. The American Society of Civil Engineers wrote a report suggesting that over the next decade we spend $2.2 trillion so we can save $1.0 trillion. And you wonder why we’re broke.

Credit where it is due

ASCE has made some significant improvements to their specific recommendations and how they talk about some of the problems. Having read these report cards for 15 years now, they have truly evolved and improved many of their specific recommendations, even just compared to the 2021 edition. (“Solutions That Work” in their parlance.) But there’s a real likelihood that these specific improvements in their recommendations will just get lost in the overall clarion call to the public and the media this week of “bad U.S. infrastructure needs more money.”

The obsession with many states and transportation agencies to fight congestion and delay is a fool’s errand, according to ASCE. We need to instead “dedicate resources to preserving a state of good repair, because no nation can build its way out of congestion,” according to this year’s recommendations. That’s a pretty stunning admission you’re not likely to hear from your state DOT and definitely not from the trade association for concrete manufacturers. They recommend focusing instead on “travel time reliability,” which is much closer to what people actually care about.

And they call for more frequent, accurate, and up-to-date data on road/bridge condition, along with more transparency within state DOTs to explain how they chose individual projects. For bridges specifically, they rightly note that the rate of improvement for repairing bridges in poor condition has drastically slowed in recent years, and they call attention to the skyrocketing number of bridges in “fair” condition, which is really where deferred maintenance shows up as good bridges degrade because maintenance is deferred.

When it comes to roadway safety, they are coming around on the power of design in impressive ways: “Incorporate infrastructure design choices that can help save lives, including reducing lane width and implementing low-cost features such as asphalt art, which can heighten the visibility of crosswalks.”

All of these changes represent a pretty significant departure from past report cards, and a pretty stark break from how they talked about these things 16 years ago. But if no new money is coming, how hard will they fight for more disruptive ideas like halting the expansion of the system in order to prioritize repair? We have learned a clear lesson from numerous reauthorization debates over the years: once new money is identified and in the bank, the impulse to talk about any policy changes evaporates.

More money will not get us where ASCE wants without making some hard choices

Here are a few facts on infrastructure spending:

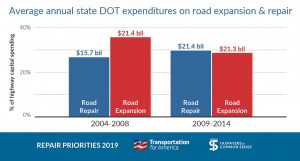

- We can’t even afford to maintain the system that we currently have. ASCE says we need to spend $87 billion per year from 2018 to 2038 just for basic rehabilitation of highways. By comparison, states reported in 2022 that they spent ~$89 billion collectively across all capital costs for roads.

- We certainly cannot afford to keep expanding our system. Each new lane-mile costs ~$24,000 per year to preserve in good condition. (And those are estimates from 2019!)

- From 2008 to 2018, even with the one-time infusion from the 2009 stimulus, the share of roads in poor condition eligible for federal funds got worse overall, increasing from 16 to 23 percent.

- The 2021 infrastructure law (the IIJA) increased highway funding by 50 percent. In 2022, states reported that they spent $22 billion on highway expansion.

- Voters don’t want to keep expanding highways. In a 2020 T4America poll, 79 percent agreed the government should fix existing roads before building new ones and 73 percent said state governments should have to justify building any new roads. In another 2023 poll, “building new highways and freeways” was the least popular long-term solution for reducing traffic.

It’s clear that ASCE values their role as the clear-eyed engineers in the room, and they do not want to prescribe how new money should be spent. But they fail to understand: To refrain from prescribing how money should be spent is to reinforce the broken status quo of how that limited money is currently spent.

The INVEST Act—a much better version of what became the 2021 infrastructure law—included an unprecedented change. States aiming to use formula highway dollars to build new road capacity would be required to demonstrate that they could maintain that road long-term. Paired with other provisions in the law, the INVEST Act would have finally started to prevent states from expanding their road networks when it comes at the expense of their repair needs. This incredibly responsible approach from 2020 was not mentioned in either the 2021 or 2025 Report Cards as a real world solution.

We really need groups like ASCE (and others) to look more critically at a federal program that has failed to deliver on priorities like safety and maintenance and may have outlived its usefulness. Can ASCE think in these terms? Despite all the good recommendations throughout this report that we really like, they’re still focused on an overall number: According to ASCE’s Bridging the Gap report, surface transportation needs from 2024 to 2033 about $3.5 trillion, of which $2.2 trillion represents the nation’s roadway system. If funding levels included in the IIJA become the new baseline for annual investment, the nation’s roadways will have a funding gap of $684 billion over the next 10 years.

Just to translate that a bit, if the IIJA—which increased highway funding alone by 50 percent—becomes the new baseline for federal transportation investment for the next 7 years, we’d still need $684 billion more? And that’s just for roads.

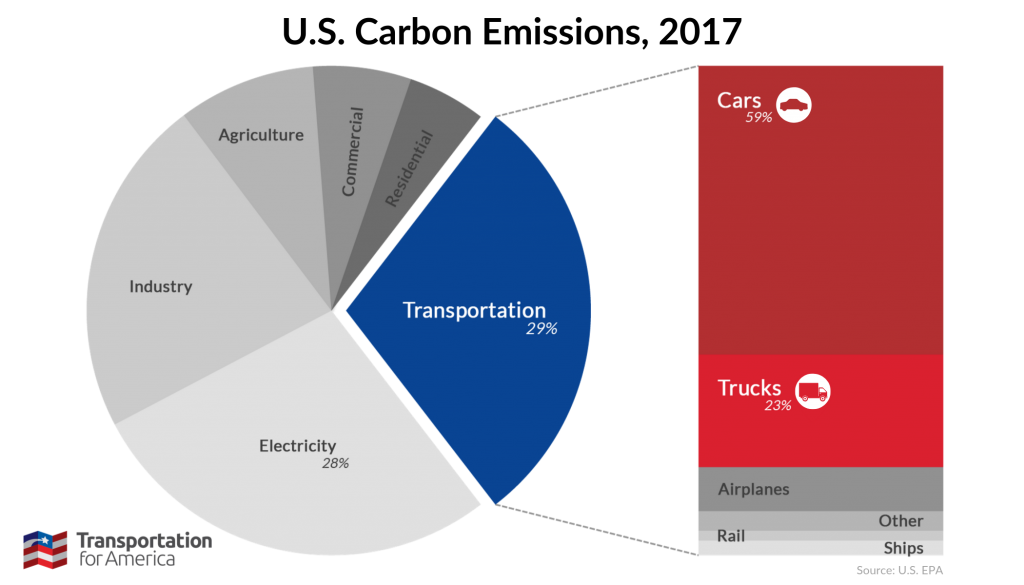

After 27 years, ASCE has evolved. But they aren’t quite ready to admit that the federal government has spent $1.5 trillion since 1991 on surface transportation and it’s resulted in subpar transit systems, crumbling roads and bridges that aren’t improving enough, historic levels of traffic deaths, and the largest sector for emissions. If you think that doubling that price tag is going to improve those outcomes, I’ve got a (poor condition) bridge to sell you.

We don’t need a penny more for a program with failing scores that have barely changed in 25 years—no matter how you measure them. We need better priorities.

Politicians (and the media) love to bemoan our “crumbling roads and bridges.” That must mean we need more money to fix them, right? Here’s a secret: most of the billions we spend every year on our infrastructure

Politicians (and the media) love to bemoan our “crumbling roads and bridges.” That must mean we need more money to fix them, right? Here’s a secret: most of the billions we spend every year on our infrastructure