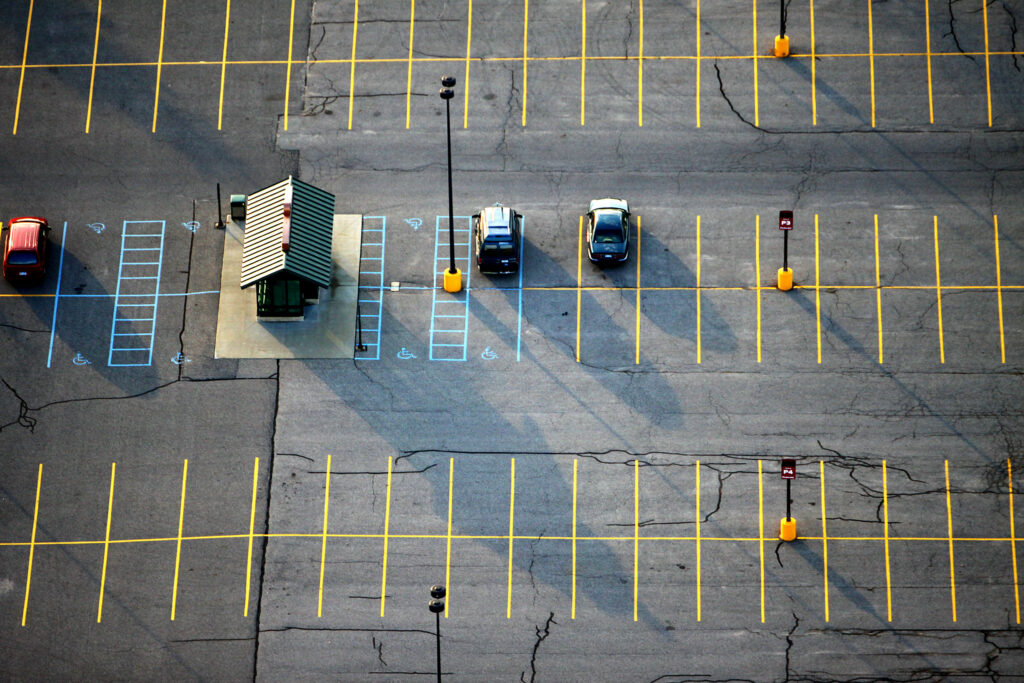

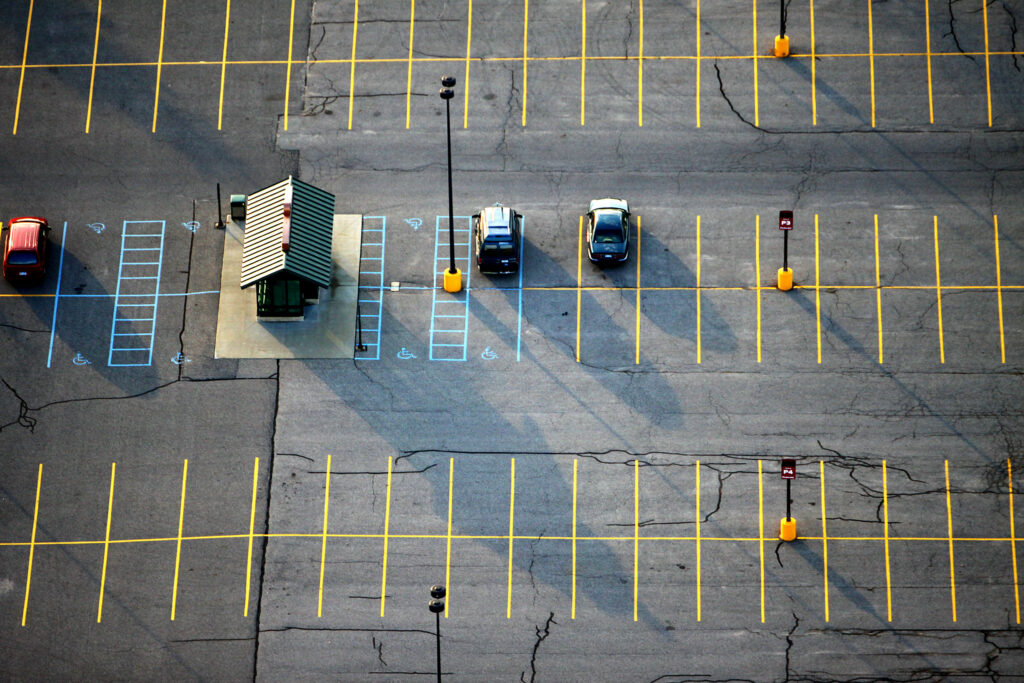

Many communities are either “overparked” (meaning they have too much parking) or are inefficiently allocating their existing parking resources. By understanding how communities’ parking assets are being used and regulated we can ensure that all modes’ access to jobs, services and amenities is supported.

How much parking do we really have?

In Miami, Florida there is a minimum of 1.5 parking spaces required per residential dwelling unit and a minimum of 3 parking spaces required for every 1000 square feet of office or commercial use. These parking requirements are quite common in community zoning codes, the regulatory framework guiding development. As a result, communities across the country now have an oversupply of parking.

Considering the factors above, it is important to be mindful of how we use parking in our communities. Building an understanding of the space available can allow communities to maximize the benefits of having sufficient parking while also ensuring that we help communities identify underutilized parking areas and enable municipalities to allocate space more effectively for various modes of transportation, including sidewalks, bike lanes, public transit, and community activation.

One essential way that parking is regulated today is through parking audits. Parking audits are comprehensive assessments of a city’s parking systems, encompassing facilities, policies, regulations, and management practices. These audits involve supporting strategic management and provision of sufficient parking and curb access around cities, and analysis to gain a deep understanding of a city’s parking resources, utilization patterns, and their impact on transportation and urban development.

How to conduct a parking audit

During a parking audit, people measure how much parking is available in a specific area. The interesting thing is that anybody can do this.

The specifics of your audit will depend on your local context. If your city is considering reducing or removing parking requirements, you might have an opportunity to partner with your local government to conduct parking audits with city staff. If city leaders and officials haven’t yet caught on to the parking dilemma in your area, you can use a parking audit to help advocate for change. In either case, using the audit to build connections with community members, policymakers, and city staff can be a powerful way to develop common ground.

To get started on a parking audit, check out these step-by-step guides from Strong Towns and the Metropolitan Area Planning Council of Boston.

Questions to consider

How long are people staying parked? Occupancy stay refers to how long a parking space is being used by a vehicle. This metric provides insights into the duration of parking sessions, helping planners understand the average duration vehicles remain parked in a specific location.

How many times was the parking space used? Occupancy turnover measures how many times a parking space is used within a given period. It provides insights into the rate at which parking spaces become available for new users. High turnover rates indicate efficient use of parking resources, while low turnover may suggest underutilization or improper pricing.

What is the ratio? Occupancy is the ratio of the number of parking spaces in use to the total number of spaces available. It is a fundamental metric for understanding the utilization level of a parking facility at a specific point in time or as an average over the day. The purpose is to provide a snapshot of how full a parking area is and whether there is excess capacity or shortages during peak times.

Collecting all this data can take time, but fortunately, there are tools you can use beyond a clipboard, camera, and a stopwatch. To cover more ground, communities like New York City or Washington, DC have deployed time-lapse photography to understand parking and loading demand. To learn more about how to take time-lapse photos, check out this guide from the District Department of Transportation.

By embracing parking audits and utilizing metrics like occupancy stay, turnover, and overall occupancy, communities can enhance accessibility, promote safety, and maximize the utilization of valuable real estate. So, whether you’re strolling, biking, or driving, let’s park smarter and pave the way for a more sustainable and accessible future.