Seattle finds a way to communicate effectively about parking prices

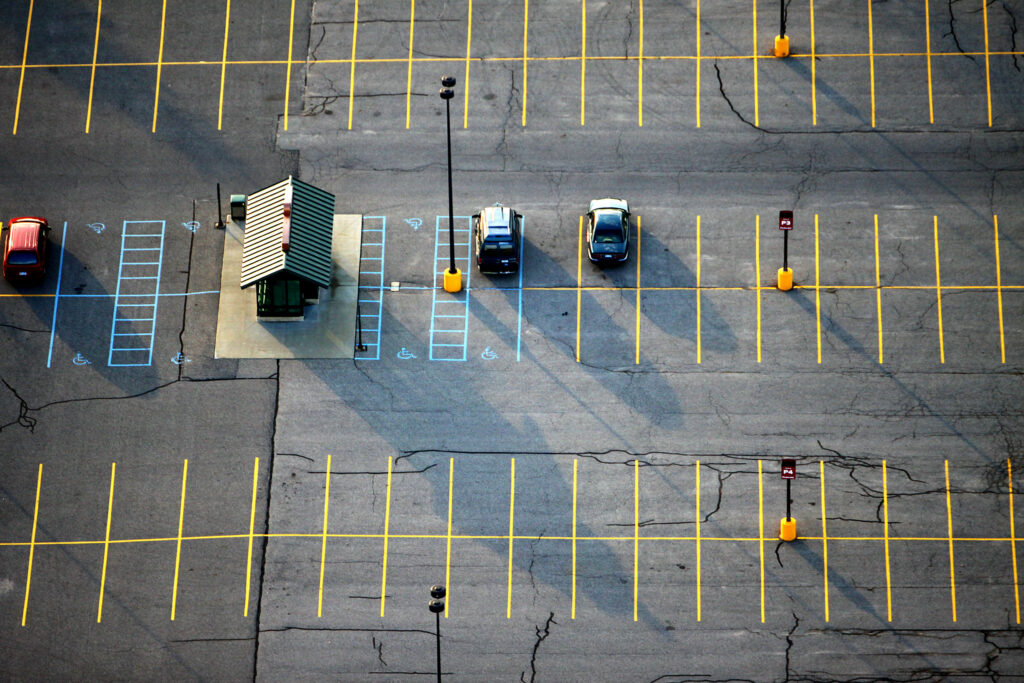

The City of Seattle (a T4America member) is one of relatively few cities that price on-street parking responsively and dynamically to most effectively manage demand.

This maximizes the use of available parking space while generating turnover so that it’s possible to find a parking spot on any block at any given time (cutting down on the congestion generated by drivers circling blocks while searching for on-street parking.). Seattle DOT recently put together this impressively clear video to explain how and why they adjust parking prices and regulation to manage parking supply and demand.

In this day and age of scarce transportation funding, communicating clearly about your city’s policies can make a big difference in building the trust you’ll need when it’s time to ask for more funding — Seattle just won a $930 million funding measure in November at the ballot — or increase your parking meter rates.