Related Resources

Community Connectors Portal: Tools for advocates > What they really meanFear of liability

Things DOTs say: “We can’t do that, we’d get sued!”

When DOTs refuse requests to make specific street design changes that are proven to improve safety, they often claim that they’re only “following the standards,” and to do otherwise could open them up to lawsuits. However, transportation engineers and practitioners can innovate for safety far beyond what they are often taught.

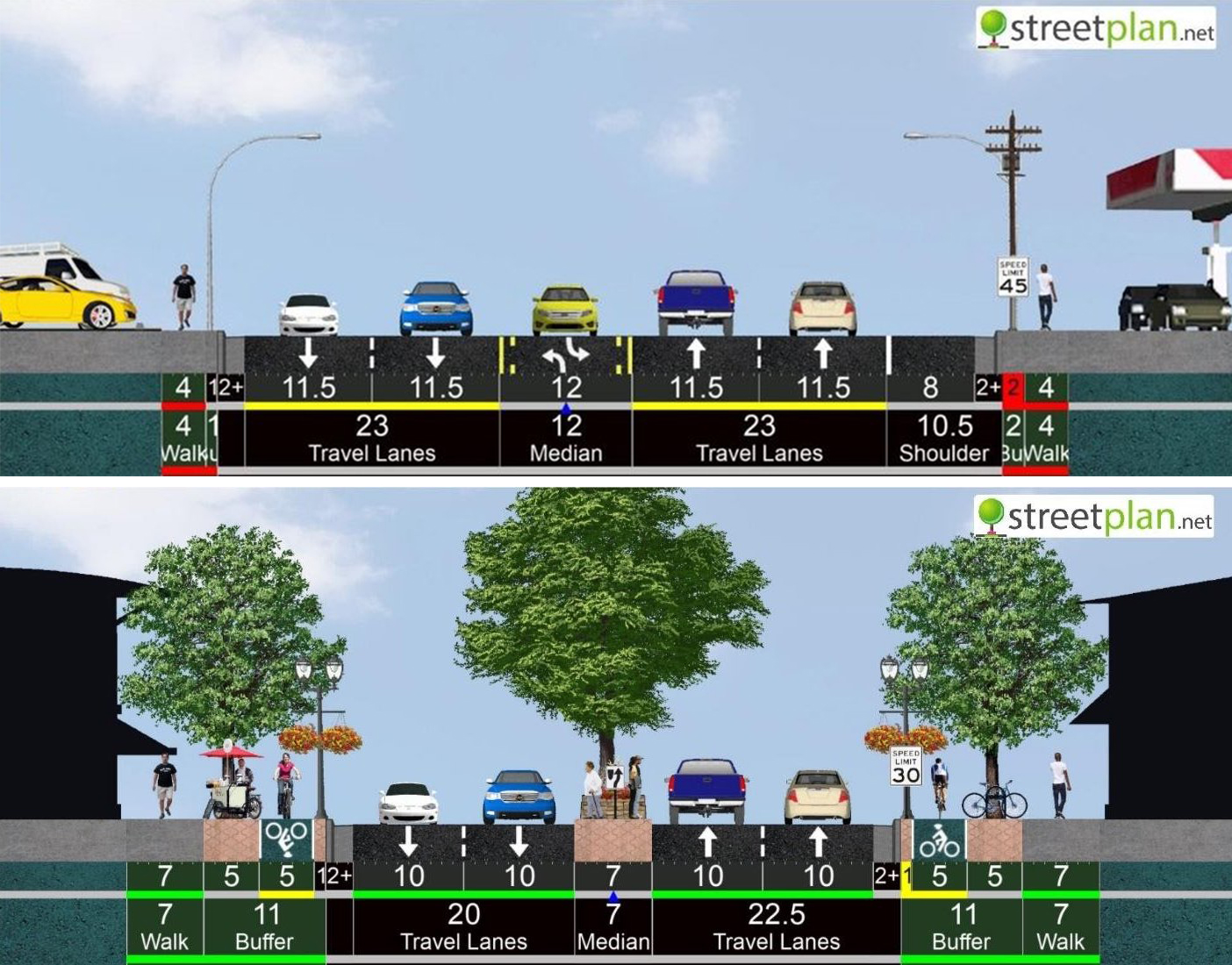

Two possible ways to design a street within the framework of current street design standards. The top is akin to a simple, rote application of standards as if they were a binding requirement, and the bottom shows a potential design requiring engineering judgment within the standards.

By applying updated standards and documenting original engineering work to create safe solutions, engineers and practitioners can be safe from litigation while deviating from design standards that are dangerous by design.1

Why are engineers scared to deviate?

The short answer is that they feel like there’s a lot at stake professionally and legally and they do take their work very seriously. Engineering schools, boards or professional organizations, and legal counsels all teach that following established standards will protect you and your agency or company, even if that results in a deadly road.

It’s worth understanding how engineers are overseen: Submitting engineering work on public roads requires one to be certified Professional Engineer (PE), overseen by a state licensing board, which takes years of schooling and continual professional training. There are often legal restrictions on who can be called an “engineer.” Some licensing boards have fined individuals for simply critiquing engineer work, while others have aggressively used their ability to fine engineers for lapsed licenses as a backdoor way to punish someone criticizing the industry and showing how it can do better.

Professional organizations in the field and many transportation agencies’ legal counsel teach engineers to fear legal challenges and tread cautiously. This helps create a cautious environment where engineers stick to what they know and adhere to legally referenced standards as a shield, even when these standards are proven to prioritize vehicular speed over safety.

Following the standards—even if they produce streets that are dangerous—is the primary objective. Doing so protects an engineer’s career, reputation, and employer.

Read Confessions of a Recovering Engineer for a tremendous first-person look at how the profession operates from Strong Towns’ Chuck Marohn. We endorse it!

Misunderstanding the role of standards

They are not black and white, prescribing narrowly specific street designs.

US law explicitly calls for the development of street design standards and recognizes several standards guidebooks. FHWA then outlines which standards must be consulted for use on National Highway System projects in federal regulations.

This does not mean a legally binding restriction to a standard. But since these standards are directly referenced in law, lawyers and judges often erroneously believe that these standards are law, and defer to professional engineers’ judgment on how design standards are best applied. And as noted in our other explainer on design standards, they allow tons of flexibility.

Even though the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (read this vital explainer on the MUTCD) and the AASHTO Green Book explicitly call for the PE to exercise engineering judgment, years of rote, standard application combined with the belief that the standards will shield engineers from legal scrutiny has resulted in static and fairly uniform applications of the standards, and less use of engineering judgment with safety as the primary goal. As a result, despite abundant evidence that standards-compliant streets and roads expose drivers and vulnerable road users to excessive, very real safety risks, professional engineers assume protection from legal risk so long as their roads conform to those standards.

The standards allow a wide range of professional latitude

This is hard to do, but when engineers assert that modifications to the design would violate standards, advocates should ensure that the PE is actually aware of the current standards and what restrictions actually exist.2 For one, the MUTCD and other standards come with no binding restrictions to design. In recent years, standards have received updates that allow for safer design elements to be incorporated, but engineers may be unaware or more comfortable simply following their established practices. The 2020 infrastructure law also made a major change to allow cities to adopt NACTO’s much more flexible Urban Street Design Guide and Urban Bikeway Design Guide design standards, even without their state’s permission. (Here’s an example of how the City of Milwaukee explained their change to city staff.)

One misconception many PEs have is that following the standards does not actually protect engineers or their state from litigation. Advocates and road users still have the ability to take issues to court when people have been harmed. (And should do so more often, in our opinion.)

While standards are the result of decades of industry experience, they also reflect decades of industry biases and tendencies to prioritize vehicle throughput over speed.

Further, the research that undergirds these standards referenced in law has, as a whole, not been validated and can still be flawed. Standards and common practice, when applied everywhere, can undermine common sense. (As Strong Towns often says, it’s “orderly but dumb”).

Unique contexts require solutions based on engineering judgment. Road design should be based on safety outcomes, not just common practice.

When the standards don’t cut it

Sometimes, a project might require a solution that does not conform to known standards. But there is always room to make exceptions using engineering judgment, as explicitly provided for in the standards. Lane width is one example—narrower lanes produce slower speeds, which is safer. As long as the decision process has been documented and approved, and relevant guidelines were consulted and reviewed (and professional engineering judgment exercised), the facility should be defensible as any other. Under some Complete Streets policies, like in the Broward County MPO, engineers are even encouraged to seek design exceptions from the state DOT to use narrower car lanes to improve safety on residential streets. This work to innovate and experiment towards solutions can be led by community and transportation leaders committed to safety.

It is tough for advocates who are not professional engineers to convince PEs who fear legal risk to deviate from their standards and the way they’ve always applied them. This is why standards like the MUTCD also need to be updated to reflect priorities for safety (and not vehicular volume) so that the status quo of standard practice can be overcome.

How can advocates fight back/what can I do?

First, be sure to read our other explainer on street design standards. Second, advocates should question why and how engineers land on dangerous designs, especially when the current design produces unsafe streets. Here are some questions you could ask:

- What street design standards did you consult to design the facility?

- Has the project engineer consulted the most relevant and modern standards?

- I’ve learned that the standards allow engineers to exercise their professional judgment, and that doing so and documenting all decisions results in just as much legal protection as treating the guidelines as a legally binding requirement, which they are not. Tell me how this balance was achieved on this project.

- What standards and guides were cited and applied? How do they meet the safety needs of all of the road’s users, including the most vulnerable?

- Has our city adopted NACTO’s Urban Street Design guide, which is much more appropriate for designing safer, more productive streets within urbanized areas? If not, why not? The 2020 infrastructure law allows our city to adopt that more flexible guide, even if the state prohibits it.

- Does the local context justify the application of the current design? (E.g. when a local-serving street exists to create a valuable place and make connections easy, rather than facilitate speedy travel through that place.)

- If a safety improvement would require a design exception, why has the design exception not been started here? Why have other facilities received design exceptions if they did not improve safety?

- What are the documented justifications for the facility’s safety deficiencies?