We recently hosted a webinar to discuss our new report, Driving Down Emissions. We received many more great questions during the webinar than we had time to address, so we are answering some of the big ones here.

Our report, Driving Down Emissions, recommends strategies to reduce growing transportation emissions by making it possible to drive less. On our recent webinar about the report, Transportation for America’s Director Beth Osborne gave an overview of why reducing how much Americans need to drive is such a crucial—and achievable—step we can take now to address urgent climate needs and make communities more equitable, and how current transportation and land use policies are standing in the way. We also heard from our partner Sam Rockwell at Move Minnesota who worked with us to produce a state-level case study.

You can view the webinar recording here.

Since we weren’t able to get to many of the great questions we received during the Q&A portion of the webinar, we grouped together (and sometimes paraphrased) a few of the big ones and answered them below.

Measuring accessibility to jobs and services came up on the webinar as a key strategy for reducing emissions. Where can I find more info about why and how to do so?

We were heartened to hear a lot of interest in measuring accessibility on the webinar. Transportation is fundamentally a means for getting people and goods where they need to go. Our historical reliance on metrics like traffic speed as proxy measures for accessibility-related outcomes has led to expanding highways whether or not those investments actually improve access—producing unintended consequences like increased sprawl, more driving, and rising transportation emissions. For decades, measuring accessibility has traditionally fallen to academic researchers and advanced modelers, but new computing power and data make it possible to measure accessibility between households, jobs, and services and apply that to transportation and land use decisions.

Here are some resources with more information about measuring accessibility:

- The State Smart Transportation Initiative (SSTI’s) work measuring access: A project of the University of Wisconsin and Smart Growth America, SSTI’s team of researchers, analysts and policy experts works with state departments of transportation, metropolitan planning organizations, and local governments to conduct meaningful accessibility analyses and incorporate them into decision-making. Their research also helps tie accessibility to other outcomes like vehicle miles traveled (VMT), mode choice, and transportation costs.

- Virginia DOT’s use of accessibility in project prioritization: SSTI supported VDOT in pioneering the use of accessibility as a criterion in transportation project prioritization with Virginia’s statewide Smart Scale program. Other states and MPOs have since begun to follow VDOT’s lead. Learn more about how VDOT evaluates accessibility here.

- Accessibility in Practice: A guide for transportation and land use decision-making: This guide for practitioners outlines general concepts, data needs and availability, analysis tools, and other considerations in measuring accessibility and using the results in decision-making.

My region continues to fund new and wider highways, with no acknowledgment of induced traffic and the fiscally and environmentally unsustainable trajectory it puts us on. How do we get elected officials to understand that building more roads does not reduce congestion?

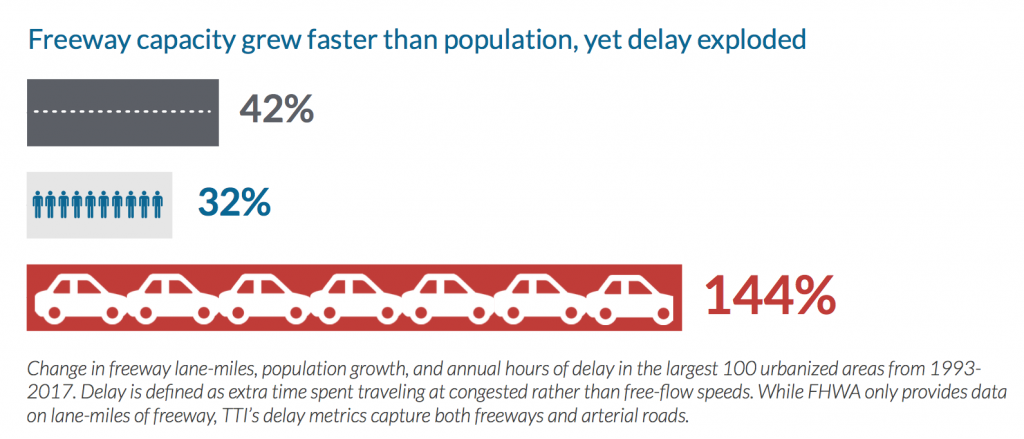

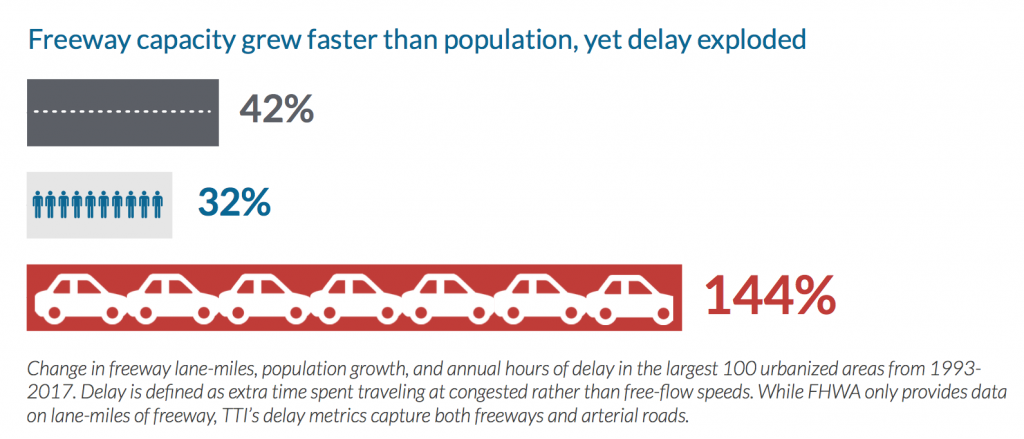

Earlier this year, we released our report, The Congestion Con, to help do just that. We analyzed the 100 largest urbanized areas in the US and found that lane-miles of freeway in those regions grew by 42 percent between 1993 and 2017, significantly outstripping the 32 percent growth in population over the same time period. Yet those investments in road capacity have utterly failed to “solve” the problem—delay is up in those urbanized areas by a staggering 144 percent. In some regions, delay even grew substantially despite very low (or even shrinking) population growth.

Using visuals to help explain less intuitive concepts like induced demand can also help make the case to elected officials facing pressures to widen highways.

What about how automobile parking creates induced demand and congestion? It’s not just about adding lanes.

True. And while cities tend to blame state departments of transportation for the role their highway investments play in inducing more car travel, local parking policy and management plays a significant role in how people choose to get around and can seriously undermine other work to manage traffic or increase walking, biking, and transit use. We hosted a webinar earlier this year entirely focused on why and how to reform parking policy. You can read a detailed recap here.

What effect will autonomous vehicles have on vehicle operation and resulting emissions?

That will depend significantly on how they are deployed and regulated, which is why we think it is so crucial to have the right policies already in place as autonomous vehicles begin to come on the market. Autonomous vehicles will hopefully provide real benefits (for example, improving access for those unable to drive), but they also have the potential to undermine safety, exacerbate inequities, increase vehicle miles traveled, and worsen land-use policies that promote sprawl and create congestion—and increase emissions in the process. You can read our recommendations to Congress for addressing autonomous vehicles in federal transportation legislation in this 2019 sign-on letter.

It is very hard to forecast bicycling trip growth if we install networks of safe comfortable facilities. How large of an obstacle do you all think this is in developing these networks, and relying on them as a part of a VMT reduction goal?

This is absolutely a challenge for determining how to prioritize investments that support biking and walking, but our tools for forecasting non-automobile travel demand are getting better—for example, the Accessibility in Practice guidebook mentioned above includes a discussion of how measuring accessibility can help predict mode share.

That said, current models for forecasting car travel generally aren’t accurate either! Transportation agencies just rely on them as if they are. This often prompts highway expansions that induce more traffic and more emissions in the process. Transportation for America has been urging federal policymakers to require the use of demand models with a demonstrated track record of accuracy in the next federal transportation reauthorization bill.

Do you think denying states funding if they do not upzone or reduce car use is a good approach to reducing transportation emissions? What about increasing the gas tax? Or having insurance companies provide a credit for reducing VMT year-over-year?

Requiring that states make progress toward climate-related goals to be eligible for federal funding is a great approach. We are advocating for language in the next federal transportation reauthorization bill that requires state departments of transportation to measure and make progress toward emissions and VMT reduction targets. The House’s reauthorization proposal over the summer, the INVEST Act, took significant steps in the right direction.

Federal policy should also help guide better land use decisions—not by requiring upzoning, but by providing modern zoning guidance to localities and updating federal laws, regulations and procedures that contribute to local land use decisions. While federal decision-makers tend to see land use as outside their purview, the federal government actually played a significant role in many of the outdated zoning codes we still see across the country today by providing model zoning ordinance language in the Standard Zoning Enabling Act of 1925. Federal decision-makers could play a similar role in creating a new template for growth that promotes shorter trips and makes it safer and easier to walk, bike, and take transit between destinations.

Incentives designed to change individuals’ travel behavior can certainly be helpful, whether through insurance companies, employer programs, or other transportation demand management strategies. However, they will have limited impact until we address the policies that are driving sprawling, car-oriented development.

How can we get lawmakers to understand that reducing car use is imperative, and that even the most ambitious climate plans do not go nearly far enough? Climate targets of net zero by 2050 are too little, too late.

Some lawmakers will be more receptive to discussing the urgency of the climate crisis than others. Yet as Driving Down Emissions discusses, there are a number of other benefits to policies that promote walkable, transit-accessible communities where residents can drive less and still meet their daily needs. It can be helpful in some cases to focus on the significant economic benefits. Polling and consumer preference research has consistently shown that millions of Americans would prefer to live in walkable, connected places where trips are short and there’s a menu of options for getting around. Businesses continue to locate in those types of neighborhoods to attract talented workers.

But aren’t we seeing a different housing trend during the pandemic—people and businesses moving away from cities toward more suburban and rural areas? Aren’t inner city properties not selling well right now?

That narrative has definitely taken hold, but it doesn’t match what we’re actually seeing in data so far. For example, research from Zilllow in May and more Zillow research in August show that suburban housing markets have not strengthened at a disproportionately rapid pace compared to urban markets—if anything, both urban and suburban areas seem to be hot sellers’ markets right now. There has been a lot of reporting from the New York Times, Wallstreet Journal, and others about the flight from cities, but it seems to be based on anecdotal data and the fact that they are located in New York City — one of two metropolitan areas (along with San Francisco) that continue to face movement out due to extremely high home prices.

How does advocacy around overturning “jaywalking” laws and addressing the over-policing of people on bikes (see NYPD targeting delivery bikes) play into shifting reliance on vehicles?

Focusing more attention on roadway design instead of enforcement is good in many ways. For one, enforcement is used disproportionately to target Black travelers and other people of color. Further when you design a road well, there is less to enforce. For example, many examples of jaywalking occur in places where there are no crossings nearby. Many mistakes made by drivers are a result of design problems. Having to fall back on significant enforcement is a sign of design failure. Better design means that walking will be safer and more attractive, and police attention can be turned elsewhere.

How do you deal with “global” factors that impact spreading out? For example, what about rural hospital and healthcare access, and the centralization that’s happening in that sphere.

Transportation planners and agencies cannot fix every development and land use decision that creates transportation problems. In fact, consolidations might be more carefully weighed with other options if the transportation impacts—like longer travel times, higher infrastructure costs, higher travel costs and paratransit costs, and more emissions—were actually considered during the decision. Transportation agencies should stop chasing development. We can’t afford to provide unfettered car access at all times of day no matter where destinations are located.

Further, these decisions have extremely negative impacts on those that do not have access to a car—there are more than one million households without a vehicle in predominantly rural counties in the US.

How do you get the general public to understand the gas tax doesn’t pay for all the roads? Around here people seem to think the roads should only be for cars because no one else pays for them.

- Point to the general fund transfers at the federal level.

- Show how many non-gas tax funds go into transportation coffers. Here is a useful resource from US PIRG.

- Point out that we wouldn’t have a backlog if the gas tax covered the cost of roads. And there are backlogs even in states that prohibit their state gas taxes from being spent anywhere but roads.

What are the biggest factors affecting people’s decisions about how to travel? It seems like GHG reduction does not factor in for most people.

Agreed. People look for travel that is safe, reliable, affordable and convenient. Many people have no mode of travel that provides all four of those factors, but they tend to choose the one that comes closest.