Shifting gears: Gender equity in transportation

Gender inequities in transportation systems have often overlooked women’s travel and safety needs. From biased crash testing to undervalued non-work trips, this Women’s History Month, we’re reflecting on how we can redesign our communities to create a more equitable and inclusive transportation system.

Past investments in transportation infrastructure have seen the adult white collar male commuter as the prototypical traveler, creating an imbalance in how we design our transportation system. It’s time to question how these design choices have left women at a disadvantage, and consider the steps we need to take to build a gender-equitable system.

Beyond the commute

Most urban transportation systems today revolve around serving the 9-5 commute. Although more women today participate in the rush hour commute as well, women and men generally share different mobility patterns, with women being more likely to take non-work trips which involve care work or grocery shopping. The differences are particularly significant when it comes to household responsibilities such as childcare, with women being three times more likely than men to do school drop-offs. Public transportation plays a crucial role in supporting these multi-purpose trips, with women making up 55 percent of transit riders.

The value and necessity of these multi-stop and non-peak journeys have long been overlooked in transportation planning. You can see this in the guidance the U.S. Department of Transportation provides on how to measure the value of time, assigning monetary value to the anticipated time-savings a transportation project will deliver for its users. There are many issues with the application of this guidance, one of them being that the language places heavy emphasis on trips made by white-collar workers over “personal” or “leisure” trips, as the USDOT memo describes them. But by not putting a value to saving people time on those non-work trips, USDOT still does not prioritize these trips.

It is essential for transportation agencies to prioritize journeys beyond white collar commuting by actively supporting shorter, localized trips. The COVID-19 pandemic showed us that looking at travel differently is possible because the pandemic disrupted and reshaped mobility patterns worldwide and continues to do so. Cities saw a rise in multi-purpose roadway spaces and Open Streets to accommodate active transportation activities such as walking and cycling. The same approach can be applied to designing transportation systems that address the travel behavior and needs of women, such as measuring access to destinations and services, analyzing access to non-work related trips, and valuing travel by transit and active transportation options, which women are more likely to take.

Gender gap in transportation safety

Not everyone experiences the same risk on U.S. roads, and women are especially at risk for being injured or killed in car accidents relative to men. One example is crash testing itself. Female crash dummies are not required for car crash test regimens required by the National Highway Safety Traffic Administration (NHSTA) and the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS), whereas a male dummy is. The “female” dummy is simply a scaled-down male dummy and, therefore, does not represent female physiological differences, like having broader hips and wider pelvises and sitting closer to the wheel than men. In the cases when this female crash dummy is used, it is used in the rear and passenger seats for most tests.

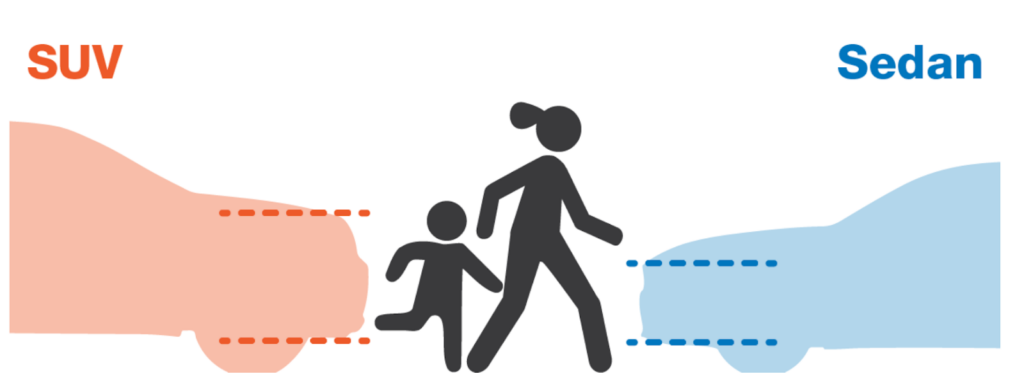

Another facet of this safety problem for women is the rapidly increasing size of vehicles that is impacting the rising rates of pedestrian deaths. The U.S. vehicle fleet has rapidly transformed, with larger trucks and SUVs replacing sedans, which featured low front bumpers with high visibility. SUVs, on the other hand, have been growing in size and weight and feature tall front hoods that can conceal visibility at intersections, particularly shorter people, and are likely to strike pedestrians in their head or chest in the event of a crash, which is more deadly. Because women (and children) are likely to be shorter, that danger is significantly more pronounced for them, and it costs them their lives.

A call for change

Women’s History Month gives us a chance to reflect on these inequities in transportation, and think about how planning, policy, and design can prioritize the needs of women. From introducing physiologically representative female crash dummies to prioritizing where and how they travel, women’s experiences in the transportation system should be more than just an afterthought.