The East Link showcases progress and enthusiasm for public transit

On April 27, 2024, Sound Transit opened up the East Link light rail line for riders to connect from Redmond to Bellevue, and ultimately to Seattle. The new rail line was met with noticeable excitement and underscores the need (and eagerness) for improved and additional public transportation.

Why light rail?

Light rail is rail-based transportation that can operate in mixed traffic (similar to streetcars, which you might find in cities like New Orleans or San Francisco). These systems are designed to carry more passengers than even a very frequent and packed bus line (like the M15 in NYC which carries at least 30,000 passengers daily) but less passengers than a heavy rail transit line (like New York’s 6 train, carrying nearly 400,000 riders a day). Heavy rail is typically utilized when spacing between stations needs to be farther apart, usually for bigger cities like New York City, which is three times larger than Seattle.

Light rail’s charm can come from many perspectives. Riders might choose to take light rail because it can be more reliable and frequent than a bus, particularly buses that have to share lanes with private vehicles. Light rail is a cheaper alternative than driving a car when accounting for time, gas prices, maintenance, and car payments, and taking this form of transit can help riders avoid the frustration of rush hour traffic. The term “light rail” is also associated with “clean” energy use and quiet, quick transport. Meanwhile, municipalities might find that light rail is a more cost-effective option than constructing a subway system.

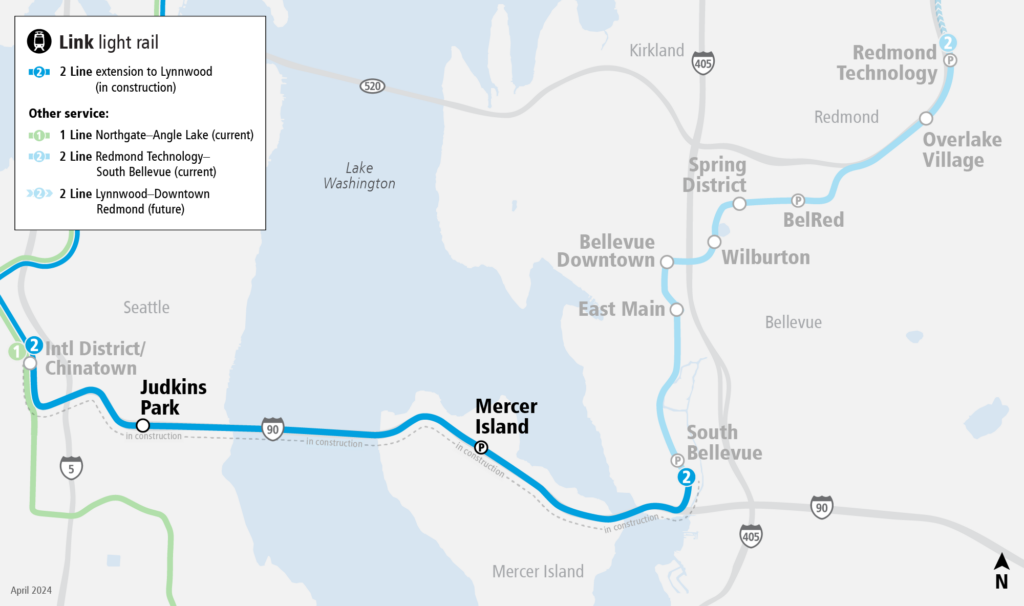

Building on the success of previous lines, Seattle has invested in the East Link light rail line (also called the 2 Line), which opened to fanfare on April 27, 2024. Once fully completed, the East Link will connect Seattle and the 1 Line (formerly Central Link from Northgate to Angle Lake) in the west to Bellevue and Redmond in the east.

Bellevue’s transportation champions

The Seattle area’s investment in public transit didn’t start with light rail. In the 1960s, the federal government offered to cover 80 percent of the costs for a potential 49-mile rapid transit system in the state. The funding and proposal were turned down due to fear of growth and financial costs. The lost opportunity spurred movement in Seattle to begin the long process of establishing an improved public transit system. There is a clear priority and demand for improved and additional transit in Washington state—and luckily, there are representatives that understand how to work the levers to obtain it.

Senator Patty Murray (D-WA) has been recognized as a champion for public transit by the American Public Transportation Association and placed a large emphasis on the importance of public transit in decreasing congestion and emissions, as well as promoting economic growth. She has had a long history with the light rail project and ensuring that Sound Transit has a future. In 2009, Senator Murray secured $1 billion in federal funding for light rail and other transit related projects.

Former mayor of Seattle and Sound Transit Chairman Greg Nickels grappled with the project from the beginning despite the uncertainty of the progressive plan. Even during his run for mayor in 2001, he campaigned aggressively on Sound Transit’s lack of funding and reiterated the importance of light rail. In 2006, when Seattle’s South Lake Union Streetcar opened and received criticism for sharing lanes with private vehicles, Nickels defended the project on the grounds that it would be built more quickly and would be less costly than alternative public transit options, all while adding more jobs.

Mike McGinn, mayor of Seattle from 2010-2013, also campaigned on the commitment to expand the city’s light rail system to connect to West Seattle. One of the roadblocks faced for the transportation project (as is the obstacle for many) is funding. Stakeholders disagreed on whether the transit line should be funded solely by the city or if it should be part of a larger regional project. McGinn called for a Seattle-only ballot measure to raise funds for the expansion of light rail to prevent money from being held up at the state and county level, as suburban politicians were more likely to be reluctant to fund anything that would not directly benefit private vehicle use. It is not uncommon to present policy proposals that will be politically unpopular and having visionaries that understand the long term benefits is one of the many levers that push products like the 2 Line forward.

Local leaders have worked especially hard to move this project forward, such as King County Councilmember Claudia Balducci, an outspoken transit and affordable housing champion. She is a former mayor of Bellevue and continued her advocacy on the 2 Line when she was elected to the city council in 2015. Current Bellevue Mayor Lynne Robinson, Deputy Mayor Mo Malakoutian, and the entire city council have also been supportive of the light rail expansion and were all present for the grand opening.

Part of supporting progress for transit is understanding where there is hesitancy from constituents and what can be done to address concerns. For example, so that the Eastside community could understand the investment and construction expectations of the project, the city demonstrated how they would strategically incorporate the light rail system into city planning. This led to the creation of the BelRed subarea plan, which aims to deliver transit-oriented development including implementing a broad range of housing and walkable/bikeable neighborhoods that connect to the regional transit network. Safety was another voiced concern, which the city addressed by having first responders train months ahead to respond effectively in tunnels and elevated tracks and activating the Bellevue Police Unit dedicated to security on transit.

Opportunities ahead for the Seattle area and beyond

Seattle has a promising transportation future ahead with the new light rail line and should be used as a guiding light for political leaders and community advocates. This was a long overdue effort for Seattle to connect the east to the west, and despite setbacks along the way, visionaries in recent history helped make it happen by standing tall against the opposition to implement the long needed project. Finally, advocating for change at the leadership level required addressing community needs in a balanced manner, standing by principles, and maintaining the vision that long-term success is complex and requires layered discourse. The story of the East Link shows that creating substantial change comes from all different levels and actors working together to make a difference.