Eliminating driver error doesn’t work. What does? Part II: Designing solutions

In part I of this blog series, we reviewed the evidence on three roadway safety strategies that rely on changing driver behavior—education, enforcement, and technology—to show where they fall short in making America’s roads safer. Design-based solutions, which accept and plan for human mistakes, can avoid the pitfalls of behavioral solutions. A recent report from New York City’s Department of Transportation sheds some light on which of those solutions work best—and for whom.

Streets and roads designed for safety—not speed—are tried and true interventions that reduce injuries and deaths. They require minimal driver education, because self-educating driver cues are built in. They have self-enforcing geometric features that force drivers to obey traffic laws without the threat of police violence. And while technology can be a critical part of safe road design, slower vehicle speeds lessen the need for fast-acting automated systems to avoid crashes.

What does a safely designed street look like? Fundamentally, it is a street with features—like narrower and fewer lanes, extended curbs, and bike lanes—that accept the mistakes made by human drivers and induce slower vehicle speeds to minimize the danger caused by those mistakes. Safe streets better reflect the complexity of a street with many different types of traffic, and are often called Complete Streets. Safe streets are going to look different in every place they’re implemented, since they are necessarily responsive to local contexts. But across the board, safe street design 1) lowers speeds and 2) considers all road users.

Evidence from the Big Apple

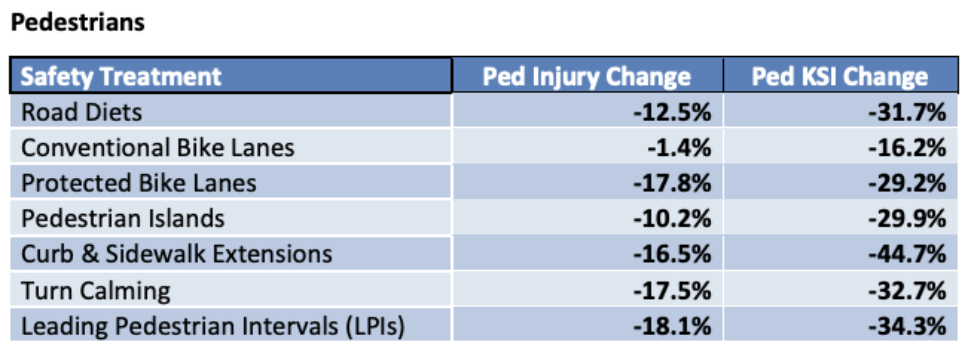

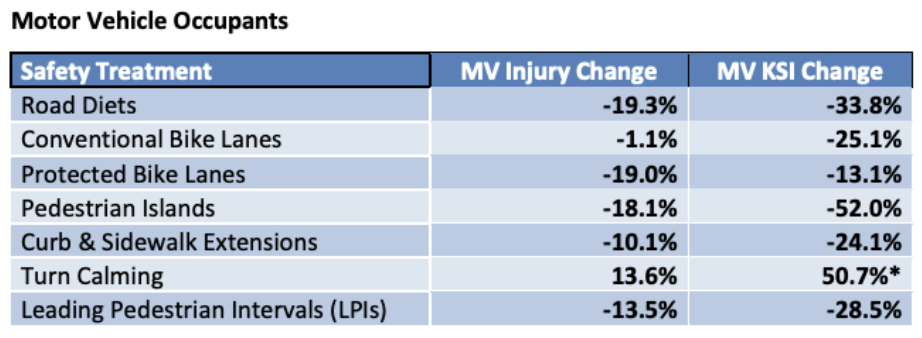

A recent report from New York City’s Department of Transportation (NYC DOT) provides some of the best data to date on the effectiveness of seven specific features of NYC’s safe street design efforts: road diets, conventional (unprotected) bike lanes, protected bike lanes, pedestrian islands, curb and sidewalk extensions, turn calming, and leading pedestrian intervals. Read more on each of these features in the report.

The results of the report show a massive impact from safe street design. In the above table, KSI stands for pedestrians killed or seriously injured. All the design features significantly reduced pedestrian deaths and injuries, with all but conventional bike lanes reducing pedestrian deaths and serious injuries by over 25 percent. These safety benefits were even more pronounced for senior pedestrians.

The safety benefits also extended to motor vehicle occupants, with all the features but turn calming (which was affected by a small sample size) reducing injuries and deaths for motor vehicle occupants at nearly the same rate as pedestrians.

Street design as a core safety strategy

The cross-user benefits of safe street and road design are not unique to New York City. A review done by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) of rural roadways in Warren County, Pennsylvania and Augusta County, Virginia found that self-enforcing, safer street design led to fewer crashes. RAO Community Health, a nonprofit in the highly car-dependent Charlotte, North Carolina, has begun modeling the benefits of safer street design to the city’s most vulnerable communities.

Every year, more states and localities all around the country recognize the safety benefits of Complete Streets, adopting policies to promote their construction. The U.S. Department of Transportation has incorporated the principles of safe street design into their national Safe Systems Approach.

The core of the success behind design is simple: it slows vehicles down. The basic fact of the matter is that vehicle speed and road safety are opposing forces. The higher a drivers’ speed, the greater risk of fatalities. No amount of education, enforcement, or technology can make up for the fact that mistakes are inevitable. Safe street design can ensure that mistakes need not be fatal.

What’s next?

Advocates and governments should leverage the well-documented track record of safe road design in reducing crashes, injuries, and fatalities (both domestically and internationally) to push for its adoption in every jurisdiction around the country. The Vision Zero movement has done excellent work in shifting the paradigm toward design. Nearly 40,000 people were killed on our roadways in 2020. If the U.S. wants to cut down this unfathomable number of fatalities, every community will need to rethink its road design standards.

Changes at the federal level could work to support these local efforts. For one, the FHWA needs to incorporate its Safe Systems Approach into its new Manual for Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), the national standards for roadway design used by every jurisdiction around the country. Better national guidance on safe streets will encourage more localities to act. But it’s worth noting that the MUTCD is not gospel. State and local governments can design roads in any way they want. Advocates should remind their local officials of this fact.

In addition, FHWA must marshal all available federal funds toward safety projects. This includes not only small, safety-specific competitive grant programs like Safe Streets and Roads for All, but also broader programs like RAISE grants and federal formula dollars. We’ve outlined a strategy for federal safety spending here > >

Now you know what works, but how can you communicate the need for design to practitioners? Stay tuned for part III of this series, which will include useful advice on doing just that.